A Very Practical Study of (Traditional) Fasting

This information is rarely discussed and definitely worth knowing.

CADE: Fie on ambitions! Fie on myself, that have a

sword and yet am ready to famish! These five days

have I hid me in these woods and durst not peep

out, for all the country is laid for me. But now am

I so hungry that, if I might have a lease of my life

for a thousand years, I could stay no longer.

—Shakespeare, 2 Henry VI

In 1450, Jack Cade led a major rebellion against the English government. He was a skillful mischief-maker who had some success as a violent revolutionary, but before long he lost popular support, was captured, and died a lonely death. In Shakespeare’s rendition of the events, Cade takes refuge in the forest after his rebellion fails, hiding there without food for the better part of a week before sallying forth and making the best of his wretched lot. He comes across a Kentish gentleman named Alexander Iden and then threatens him; Iden isn’t about to be abused by some vulgar nobody that just crawled out of the woods: “Why, rude companion, whatsoe’er thou be, / I know thee not…. / But thou wilt brave me with these saucy terms?” Cade, perhaps somewhat maddened by hunger, defies him: “Brave thee? Ay, … I have eat no meat these five days.” A swordfight ensues, and Cade’s mischief-making comes to an abrupt end. Before he breathes his last, he is able to declare (with fine Shakespearean diction) that “famine, and no other, hath slain me.”

Much could be said about this scene; our concern here is Cade’s fast. Modern readers might look askance at Shakespeare’s suggestion that a man who has eaten nothing for five days could walk through the woods, and climb the wall of a gentleman’s garden, and even draw his sword against a well-fed man and then fight him to the death. Is this just another case of Shakespearean fancy? Is it yet another moment when the Bard seems decidedly uninterested in plausibility?

Not at all—though Cade likely would have felt an overpowering urge to find sustenance, his actual energy levels would probably have been normal. In fact, if he had a bit of extra flesh on his body when he first wandered off into the woods, he might have been in excellent physical condition at the end of those five days.

I’ll go even further. I have personally observed someone voluntarily eat nothing—nothing—for much longer than five days, leading a normal active life the entire time, and with physiological benefit rather than harm. Oh, the marvels of the human body! It was designed, with perfection and complexity beyond all comprehension, by a good and loving God, who knew that “to all things there is a season”: a time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance; a time to eat, and a time to fast.

Disclaimers:

My intention here is to give knowledge, not medical advice (or any other type of advice). Bodies are different and sometimes react to things, especially new things, in unpredictable ways. I am of the opinion that we modern folks could be a bit bolder in our pursuit of (physical or spiritual) health, but prudence and caution, combined with carefully listening to the body, are nonetheless essential.

This is emphatically not a “five reasons why you should be fasting” type of article (perish the thought!). I’m not a physician, and I’m not a priest; ascetic practices, for the body or the soul, involve personal decisions that are none of my business. I am, however, an educator, and my objective here is simply to educate. More specifically, I want to share valuable information and thought-provoking perspectives that are grievously underrepresented in current discussions of health and spirituality, and which have the potential for truly life-changing, even life-saving, effects.

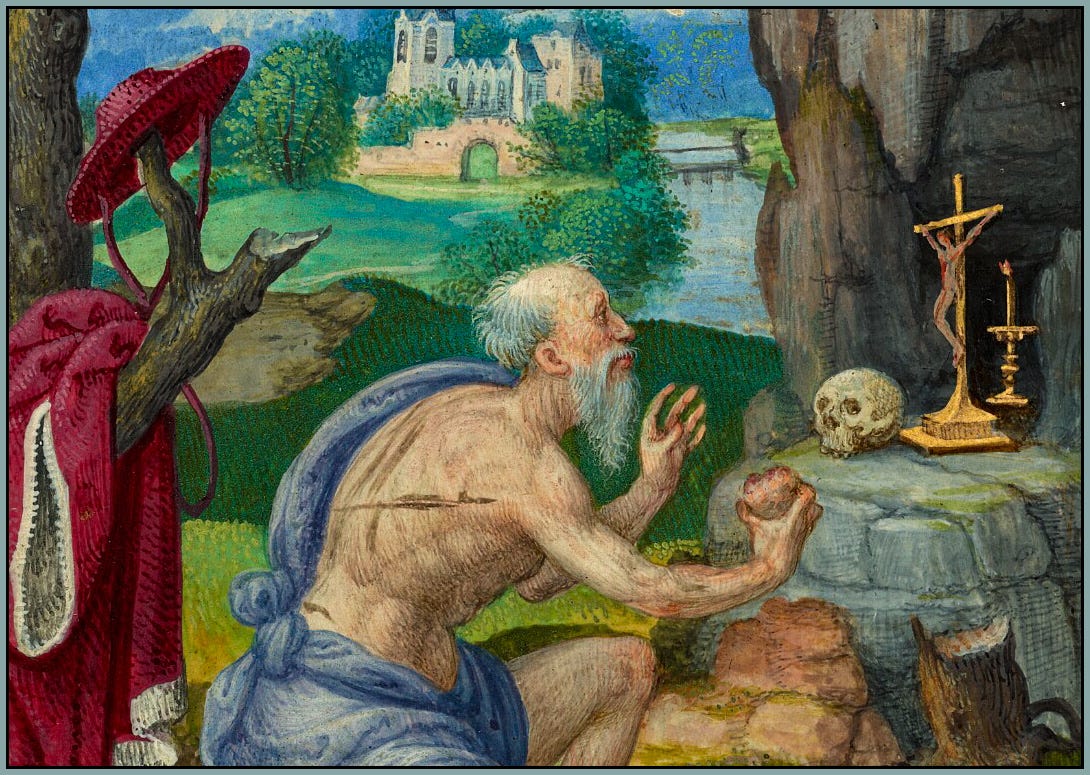

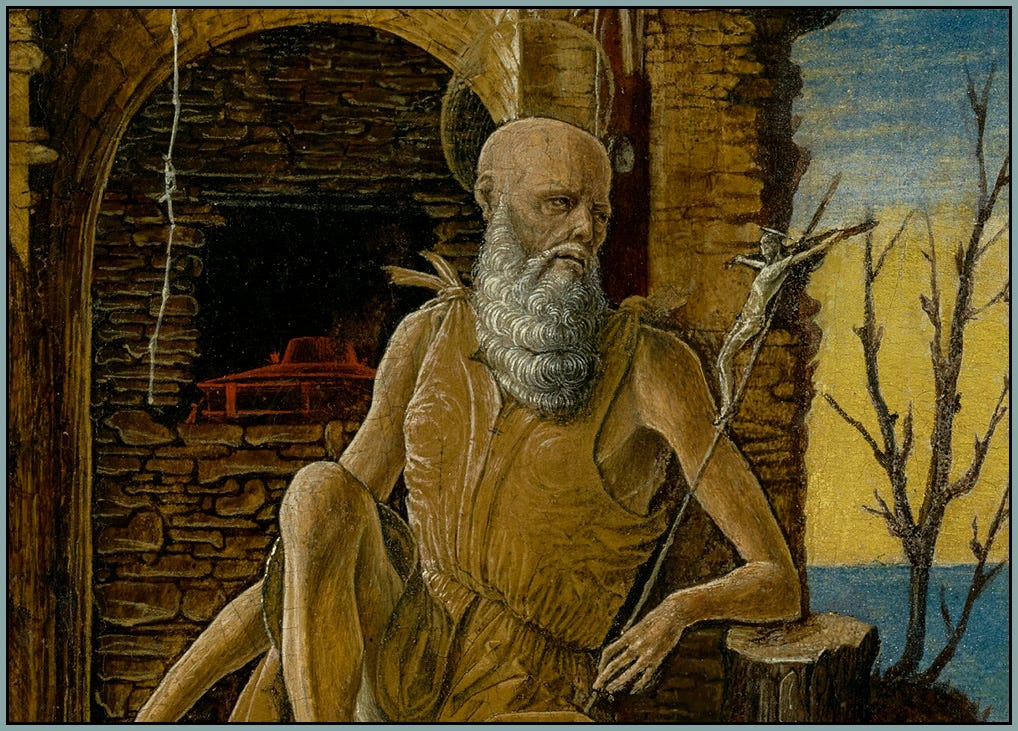

Part of my interest in this topic derives (as you may have guessed) from medieval culture, in which fasting—practiced on a staggering scale, year after year after year, by peasants and kings and everyone in between—was an issue of great religious and social importance; Tuesday’s post will continue this discussion by exploring the history and significance of fasting in the Middle Ages. And let me state clearly that I mean fasting in the strict and basic sense: I refer not to temporary renunciation of chocolate, or abstinence from meat, or the consumption of bland food, or meals of reduced size, or any such thing. I refer to eliminating meals and snacks, such that nothing whatsoever is eaten for a significant portion of the day (or in extreme cases, for multiple days).

As you may already know, the Via Mediaevalis newsletter is not fundamentally about how people lived in the medieval world; it is fundamentally about how we live in the modern world. However, we seek inspiration and guidance from medieval Christendom because it is an era that utterly surpassed our own in many important ways, and that supplies a perpetual and incomparable feast for the eyes, the intellect, and the imagination.

What medieval Christendom did not do is supply a perpetual feast for the stomach. Lent and vigils and Ember fasts came around with (perhaps disconcerting) regularity, and members of monastic communities seriously restricted food intake for large portions of the year. I am perfectly willing to accept that we, for various reasons, should not or cannot fast as our medieval brethren did. But we should nonetheless seek to learn from their fasts, and we can do that more easily if we understand fasting not only as an ascetic practice but also as a physiological and psychological phenomenon.

In 1965, a “grossly obese young man” living in Scotland sought medical assistance for weight loss. He began a short fast and felt fine; since he wanted to reach a desirable weight more quickly, he decided to extend the fast. When all was said and done, he had lost 276 pounds. He ate nothing for 382 consecutive days. I didn’t get this story from the rumor mill; my source is a paper in a peer-reviewed medical journal. The patient freely drank non-caloric fluids, used daily vitamin supplementation but not much mineral supplementation, and was under medical supervision. The authors of the paper concluded that “prolonged fasting in this patient had no ill-effects.”

For a long time, fasting scared me. I vaguely imagined that missing a meal or two would do something bad to me. I’m not even sure what exactly—maybe I would faint? or have crippling stomach cramps? or get scurvy and die? Who knows. It hardly mattered, though, because food was always available and I have never been overweight, or anything close to overweight. Mine is the opposite problem: poor appetite, poor digestion, poor muscular development. I’m currently 6'1'' and 155 pounds; the photo below gives you an idea of how very thin I am. From a psychological standpoint, extended fasting is still a struggle for me, because I have so little fat to burn and dearly want to retain the small amount of muscle that I manage to build through weight training. I nonetheless have done a great deal of fasting in an attempt to overcome chronic illness, and my body adapted to it extremely well.

A big fasting breakthrough for me was just understanding the math. One pound of human body fat contains about 3500 calories of energy. Compare that number to the energy required by the human body each day: for most adults, the number is somewhere between 1600 and 3000 calories. Those figures are somewhat misleading, because when food intake is restricted, the body (quite reasonably) goes into energy-conservation mode and thus needs fewer calories. However, let’s ignore that for now and just use 2500 calories as a representative daily energy requirement. We see immediately that eating absolutely nothing for an entire day will burn not even one pound of fat—only about 0.7 pounds (2500 ÷ 3500 = 0.71) is needed to get through the day with normal energy levels. This number has been verified experimentally. The young man mentioned above, for example, lost weight at an average rate of 0.72 pounds per day, and other long-term fasts that had been studied at the time achieved weight-loss rates of 0.41 and 0.67 pounds per day. The 0.41 number indicates that the patient’s body used only about 1400 calories per day. (Note that dramatic weight loss at the beginning of a fast occurs because fasting stimulates natural diuresis; someone who abruptly stops eating might lose five pounds of water weight before burning one pound of fat.)

A healthy, well-fed adult will typically have at least 15% body fat; in a modern affluent society the number will often be much higher. But let’s say a 180-pound man has 15% body fat: that’s 27 pounds of total fat reserves, and 27 pounds ÷ 0.7 pounds per day ≈ 38 days. In other words, this person would have to eat absolutely nothing for 38 days in order to burn all the fat on his body. I realize that zero percent body fat is a very bad place to be, but the point is, the human body stores a lot more energy than we sometimes think.

Another example: let’s say a 200-pound Christian with 20% body fat (= 40 pounds total fat) wants to eat only one meal per day every day during Lent. This is a prolonged fast, and we’ll assume that the body gets a little worried and decides to conserve energy by lowering the metabolic rate. The average daily energy requirement is thus reduced to about 2000 calories, and if the (understandably hungry) penitent brings in 1000 calories at the one daily meal, that’s a deficit of 1000 calories per day, or about 0.3 pounds of body fat. Thus, total fat loss after forty days of Lent will be only 12 pounds, out of the original 40 pounds! I think that many people would be delighted to lose 12 pounds, and if the one meal is wholesome and nutrient-dense, it should provide adequate vitamins and minerals for most non-pregnant, non-lactating adults. If the penitent added an evening collation to the regimen and ate heartily on Sundays, he or she might look and weigh much the same on Easter Sunday as on Shrove Tuesday.

I apologize if this section has been somewhat dull and technical, but there is a crucial message here: the traditional Lenten fast is remarkably feasible from a physiological standpoint. Medieval folks in general ate quite well during most of the year, and there was no reason for them to worry about losing five or ten or even fifteen pounds during Lent—especially considering that Lent was preceded by the Christmas-Epiphany feasting season and followed by the Easter feasting season.

None of this information, I hasten to add, suggests that fasting is easy. Though the body may endure calorie restriction (and even temporary starvation) with relative ease, the mind wants food. Our desire to eat—a strong and sometimes overpowering primal urge—is rooted not only in metabolic needs but also in the emotional, social, and spiritual facets of our being. Fasting is, and always has been, hard. It is, and always will be, a penance. There’s no way around it.

Faith was almost universal in the Middle Ages; heroic sanctity was not. It is unwise to sever ourselves from the pious or penitential practices of the noble past by assuming, perhaps subconsciously, that modern bodies and souls just can’t do what medieval Christians did. Today I have attempted to briefly demonstrate that, generally speaking, the strict and extended fasts of the Middle Ages pose no threat to bodily health and will not lead to catastrophic weight loss or severe fatigue. Indeed, many people nowadays are fasting in a rather Lenten way simply because they want to improve their health, and we should be thankful that modern science is confirming ancient wisdom—namely, that fasting is one of the safest, most efficacious, and most widely applicable therapies in existence.

The information I’ve shared today is, in my life, neither a burden nor a guilt-trip. It is simply freedom: the freedom to skip a meal or two when eating is inconvenient; the freedom to help my body detoxify without spending any money; and yes, the freedom to fast as my medieval forebears did. In the eleventh century, the progenitor of the Keim family fled the world and lived as a goat-herding hermit in the Alps, and his son fought in the First Crusade. These sound like people who made fasting an important part of their life, and I’m glad that it can, in some small way, be a part of my life as well.

This was very helpful and reassuring, thanks. I've got middling metabolic problems - that affect more than being overweight - since chemotherapy for cancer 12 years ago. I've been wanting to try intermittent fasting to treat them for a while but had feared I'd run into serious problems with fatigue. I went through a long period of isolation after the Norcia earthquakes, and was fairly seriously depressed (I mean clinically) through much of it, one upshot was I barely ate. I didn't lose any weight at all, but was plagued with extreme fatigue and memory an cognition issues, sleep problems and all sorts of things. But I learned that the problem wasn't the low caloric intake but magnesium, iron an potassium deficiencies. I found this out by accident. I had a problem with my left eye, and went to the eye doctor who prescribed a special supplement that had a bunch of eye-related things but also magnesium and potassium. My GP added a vitamin C, iron and B regimen, and the effect felt miraculous. I felt as though I'd suddenly "woken up" from some strange waking dream state. The effect was so dramatic I've been keeping up the regimen ever since. Every time I let it slide the weird, foggy half-dreaming state comes back and I have no energy and my mood sinks. As long as I keep up the supplement regimen, I feel perfectly fine, whether I eat a lot or very little. Before reading this, the idea of trying intermittent fasting to finally drop the 40 pounds of post-chemo weight always made me worry the horrible low metabolic situation would return, but now that I think about it, the Bad Thing - which can be crippling - really is more to do with these chronic (chemo-related) deficiencies. I bet if I kept up the supplements very strictly, and kept a record to monitor, I could do the fasting thing after all. I think I'm going to give it a try.

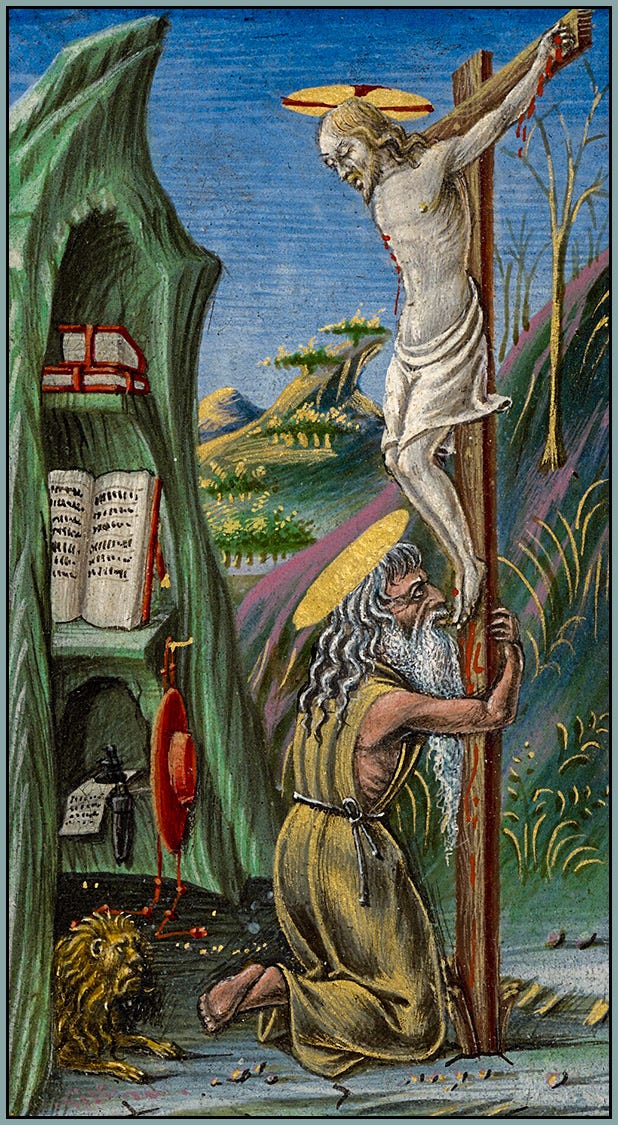

Reading 4: From the Book addressed To Virgins by Saint Athanasius

Bk. ii. If any should come and say unto thee, Fast not so often, lest thou injure thine health, believe them not,neither listen to them. They are but the tools of the great enemy to suggest such a thing unto thee. Remember how it is written that when the three children, and Daniel, and the other lads, were led captives by Nebuchadnezzar King of Babylon, and it was commanded them to eat of his Royal table, and to drink of his wine, Daniel and those three children would not defile themselves with the King's table, but said unto the eunuch into whose keeping they had been given, Give us of the fruits of the earth, and we will eat. And the eunuch answered them, I fear my lord the King, who has appointed your meat and your drink, lest perchance your faces should appear unto the King worse - liking than the other children, who are fed from his Royal table, and he should punish me.

Reading 5: Then they said unto him Prove your servants ten days, and give us herbs. And he gave them pulse to eat and water to drink and, when he brought them in before the King, their countenances appeared fairer than all the children which did eat the portion of the King's meat. Seest thou what fasting doth It healeth diseases, it drieth up the humours of the body, it scareth away devils, it purgeth forth unclean thoughts, it makes the intellect clearer, it purifieth the heart, it sanctifieth the body, and in the end it leads a man unto the throne of God. Think not that this is rash talking. You have the testimony of this in the Gospels under the sanction of the Saviour Himself. His disciples asked Him why they could not cast out an evil spirit, and He said unto them This kind can come forth by nothing but by prayer and fasting.

Reading 6: If any man therefore be troubled with an unclean spirit, if he bethink him of this, and have recourse to this remedy, namely, fasting, the evil spirit will be forthwith compelled to leave him from dread of the power of fasting. Devils take great delight in fulness, and drunkenness, and bodily comfort. There is great power in fasting, and great and glorious things are wrought thereby. How comes it that men work such wonders, and that signs are done by them, and that God through them gives health to the sick, unless it be from their ghostly exercises, and the meekness of their souls, and their godly conversation To fast is to banquet with Angels, and he that fasteth is to be reckoned, so far, among the Angelic host