Today, beloved, we celebrate in the joy of one solemnity, the festival of All Saints, in whose companionship the heaven exults; in whose guardianship the earth rejoices; by whose triumphs the Holy Church is crowned.

These are the opening words, translated from the Latin, of a sermon delivered by the Venerable Bede in the early eighth century. Medieval Christians loved to venerate and invoke the religious heroes who had gone before them in the arduous battle of life, and their local saints, who perhaps had no formal commemoration in the Church’s calendar, were especially dear to their hearts. The Kalends of November was dedicated to honoring all those blessed souls who had served God in life and reached the heavenly country after death; this date was established in Rome in the eighth century and later extended to the universal Church.

The logic behind All Hallows’ Day is explained quite clearly in a sermon written by an eminent tenth-century churchman named Ælfric:

Holy teachers have taught that the faithful church should celebrate and piously solemnize this day to the honor of All Saints; because they could not appoint a festival separately for each of them, nor to any man in the present life are the names of all of them known.

Just in case there’s anyone out there interested in (or maybe already proficient in?) Old English, the passage in the original language is given below. If you haven’t studied Old English and would like to give the pronunciation a try, here are some (very) brief guidelines: assume that stress falls on the first syllable (it usually does), pronounce “æ” like “a” in “cat” and “þ” or “ð” like “th,” shift the vowels toward their Latin sounds, don’t treat any letters as silent, and otherwise use modern English pronunciation but with an accent that makes you feel like you’re celebrating the feast in a mead-hall with Beowulf.

Halige lareowas ræddon þæt seo geleaffulle gelaðung þisne dæg Eallum Halgum to wurþmynte mærsige, and arwurðlice freolsige; for þan ðe hi ne mihton heora ælcum synderlice freolstide gesettan, ne nanum menn on andweardum life nis heora eallra nama cuð.

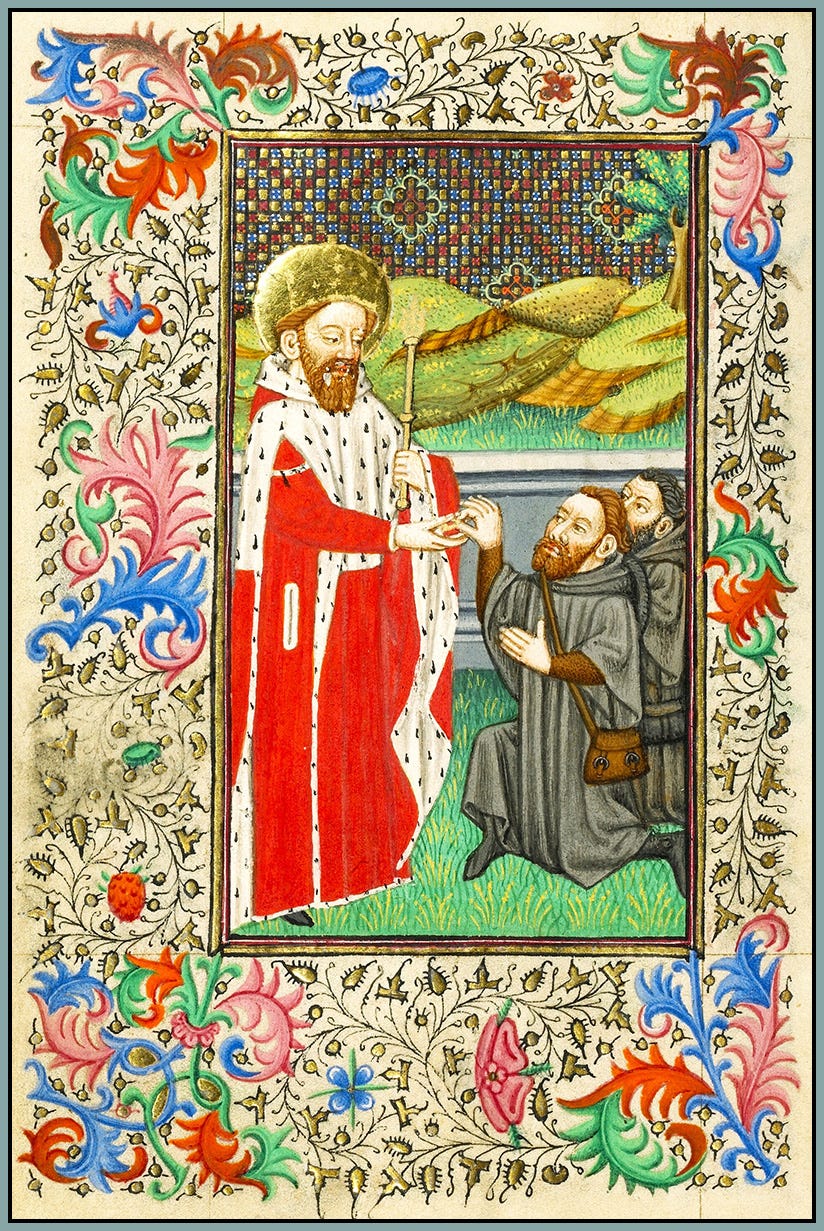

We’ll take a break from calendrical artwork this week while we enjoy, in honor of Hallowmas, some medieval depictions of Anglo-Saxon saints.

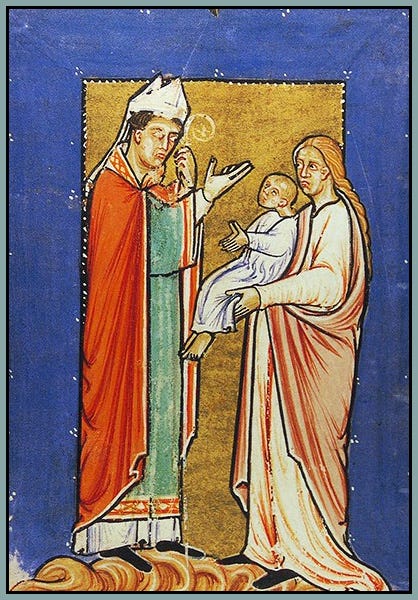

Cuthbert of Lindisfarne (d. 687), a Benedictine monk and bishop, miraculously heals a child in this illumination from an early-thirteenth-century English manuscript.

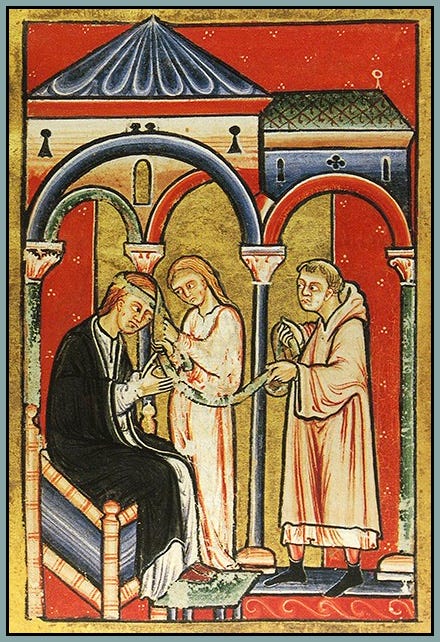

Here we see St. Cuthbert again, now appearing as a tonsured monk. He holds a girdle that is wrapped around the head of Abbess Ælfflaed of Whitby, whom Cuthbert also miraculously healed. She was sister to the king of Northumbria and eventually honored as a saint herself.

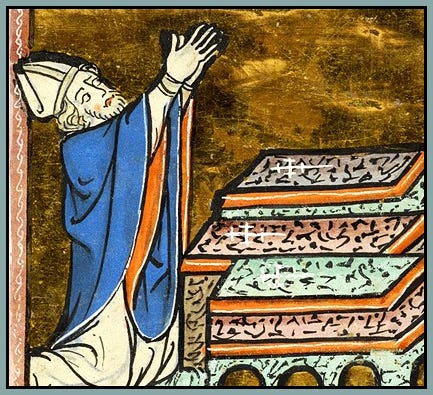

Dunstan of Canterbury, a tenth-century abbot and archbishop, kneels and prays before three tombs. The image is from an early-fourteenth-century French manuscript.

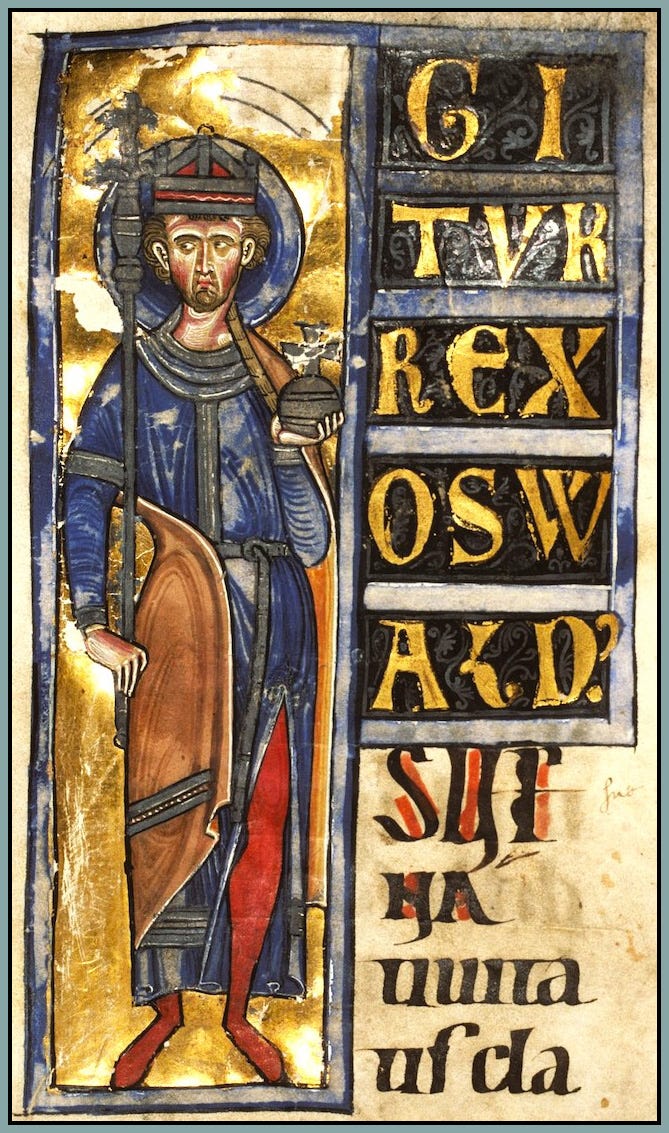

This next illumination, damaged though wonderfully vibrant, depicts King Oswald (d. 642) and comes to us from an early-thirteenth-century German manuscript. Oswald ruled Northumbria and was a formidable leader in other parts of England as well. He was killed by a pagan king and therefore venerated as a martyr. The rectangle that contains his image is actually the letter “I”; what we’re seeing here is a historiated initial for the phrase “IGITUR REX OSWALD.”

Let’s conclude with a few saintly Anglo-Saxon monarchs. First, King Æthelberht of Kent (d. 616), the man who received the missionaries sent by Gregory the Great. He converted to the new Faith and was England’s first Christian king.

(The image is labeled with the Latin version of Æthelberht’s name, but actually I’m not sure if this refers to Æthelberht of Kent or Æthelberht of East Anglia. Both were kings, and both were saints.)

Next, King Alfred the Great (d. 899):

It’s not a very impressive illustration, I must admit. Illuminations of King Alfred are surprisingly scarce, perhaps because his status as a saint was rather “unofficial.” Saint or not, he is one of England’s most successful and virtuous monarchs.

Finally, St. Edward the Confessor. He died in the same year that Anglo-Saxon England did: AD 1066. May they rest in peace.

Thank you for these wonderful illustrations. My favorites are Dunstan praying (amazingly powerful) and King Oswald. How clever that he is made the I of igitur.