“Follow Me”: An Illumination for St. Andrew’s Day

“And he saith unto them, Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men. And they straightway left their nets, and followed him.”

It was my pleasure to co-author this essay with Amelia McKee, who writes the excellent Substack newsletter Art for the Liturgical Year. This special article, produced in honor of St. Andrew’s feast day on November 30th and marking the beginning of a new liturgical year, combines the normal Friday installment of The Medieval Year and the full-length essay normally posted on Sunday. The next post for Via Mediaevalis will arrive in your inbox on Tuesday.

If you were to turn to Hollywood to learn about the medieval period, you may come away with the impression that their world was drab, dark, and dismal. This impression could not be further from the truth, for the age was in fact profoundly colorful and shows a great appreciation for the power of color to beautify our lives, evoke salutary emotions, create visual harmonies, and symbolize higher realities. The aesthetic of these movies tells us more about our own society than about medieval society—as does much else that modernity has taught us about the premodern past, for the modern mode of thought turns the historian’s lens into something more akin to a mirror. Professor Brad Gregory, historian at Notre Dame, said it well:

Present values—regardless of their content—invariably construe the past in their own image…. The self-professed reasons why people did what they did are suspect in proportion to the moral offense they give to modern or postmodern sensibilities.

The ideologically modern mind looks at the Middle Ages and sees, first, itself: moral relativism, rationalism, empiricism, religious indifferentism, democratism, and so forth. It then sees medieval society as essentially the opposite of itself, noticing above all the many and varied ways in which that society offends against modernity’s foundational ‑isms. One might then conclude that the medieval world—submerged as it was in ideological darkness, and possessing supposedly dismal ideas about doctrinal conformity, or the natural law, or social hierarchies, or the possibility of eternal damnation—must also have been, literally, rather dark and dismal.

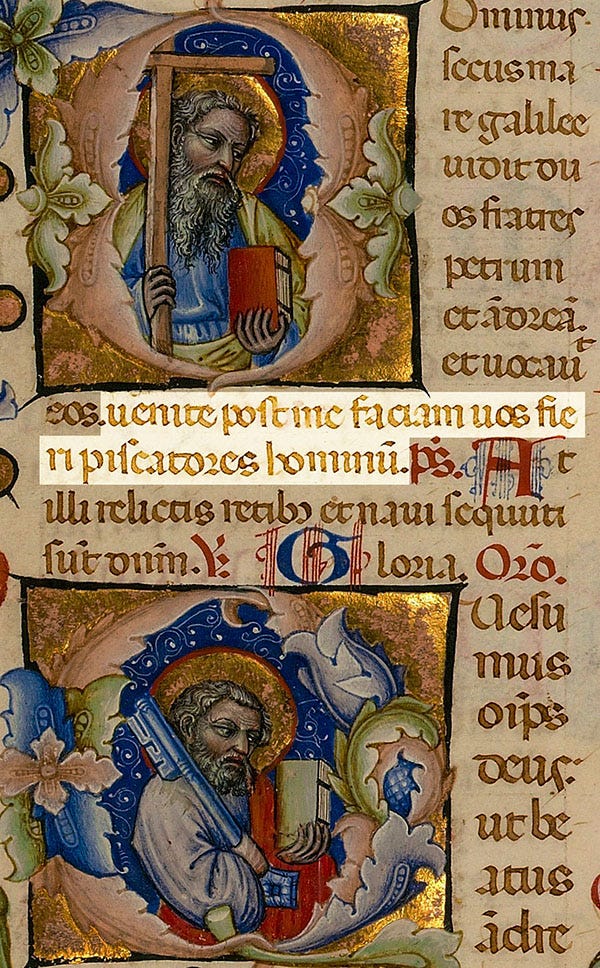

And yet, as we turn the leaves of an illuminated manuscript, we see something very different. We find ourselves transported to a miraculous, imaginative, and often jovial world full of lush vegetation, fantastical creatures, captivating geometrical motifs, deeply human characters, and vibrant—sometimes exquisite—color. We may even find ourselves thus transported when looking at just a single page in an illuminated manuscript; such is the case with the enchanting page we want to share with you today, which opens the sanctorale of a sumptuous missal commissioned in the late fourteenth century by Cosimo de' Migliorati, an Italian bishop and cardinal who later became Pope Innocent VII. The missal’s anonymous artist is known as the Master of the Brussels Initials, because he painted decorative initials in a Book of Hours now held in the Royal Library of Belgium. The artist’s vivid and exuberant style, which shows Italian influence and in turn influenced French artistic culture, invites us to reflect on the vitality of manuscript illumination in these last few decades before the invention of the printing press, which was its death knell.

The missal’s sanctorale, which contains liturgical texts for the commemorations of saints, begins fittingly with the feast of Saint Andrew, for he was the “first called”:

The next day, John stood again, and two of his disciples. And he beheld Jesus walking by, and said, Behold the Lamb of God. And the two disciples heard him speak, and followed Jesus…. They came and saw where he dwelt, and abode with him that day: for it was about the tenth hour. Andrew, Simon Peter’s brother, was one of the two which had heard it of John, and that followed him. The same found his brother Simon first, and said unto him, We have found the Messiah. (John 1:35–41)

If we look at this image as a unified composition, we see that the Word is very much alive. Indeed, we could say that the emergence and growth of living things, in both the material and the spiritual sense, is the heart of this painting’s artistic logic, and a lens through which we can contemplate its mysterious visual poetry.

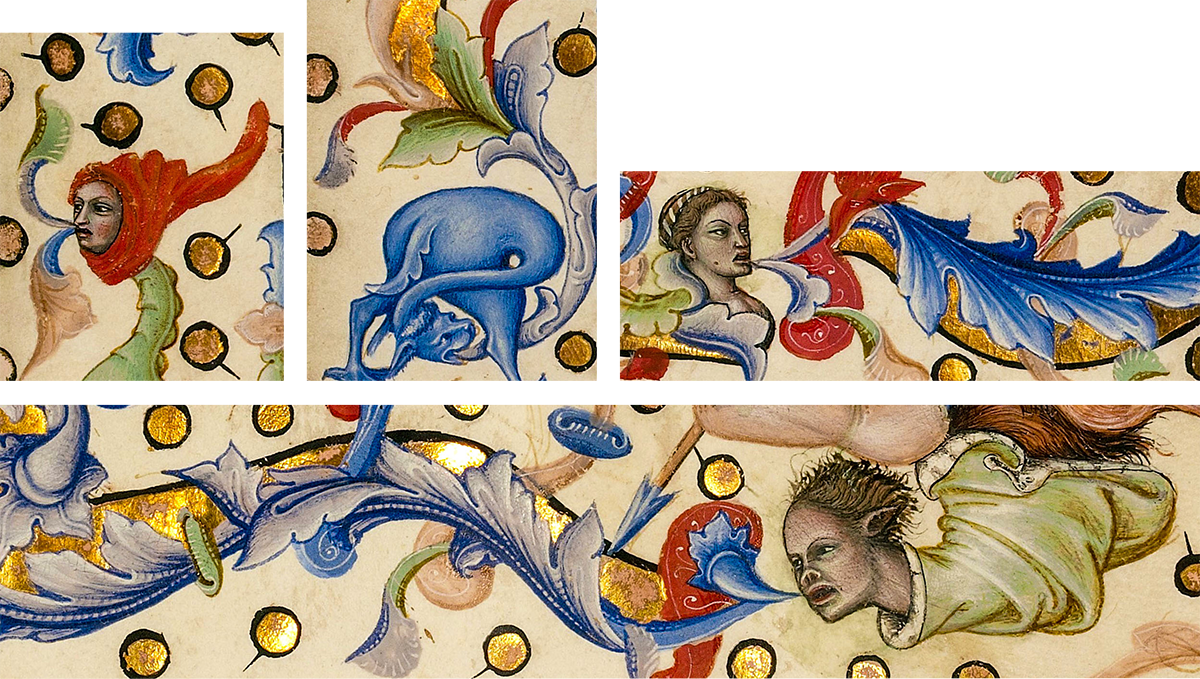

Let’s consider the decorative border, which is a masterful achievement in itself. There is a sense that the words of Christ at the center of the page have created the beautiful decoration around it, as though the work of the human artist is an allegory for the work of the divine Artist, whose Word brought forth Creation: “And God said, Let the earth bring forth grass, herb yielding seed, and fruit tree bearing fruit…. And the earth brought forth grass, herb yielding seed after its kind, and tree bearing fruit” (Genesis 1:11–12). The border vegetation, with its elegant palette of harmonious, organic hues, takes on a life of its own as it rhythmically curls around the sacred texts. It grows in response to the divine Word, mirroring the spiritual growth taking place in the souls of Peter and Andrew as they respond to the words of Christ, which are literally near and between them as part of the vigil’s Introit: Venite post me: faciam vos fieri piscatores hominum—“Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men.”

The theme of life-giving words even helps us to decipher cryptic portions of the image’s fascinating marginalia. Scholars continue to study and theorize the chimeras, fantastical forms, and comical scenes that inhabit, sometimes rather inexplicably, the margins of medieval manuscripts. Perhaps their most important purpose is to evoke the characteristically medieval mundus inversus—the “world turned upside-down” that amuses and intrigues us while also reinforcing, in the manner of a literary foil, the superiority of God-given order and wholeness. In the illustration for St. Andrew’s Day, however, the marginal creatures have an additional role: they seem to speak forth biological life, thus recalling the creative power of divine speech and the spiritual fecundity of those incomparable words that Christ addresses to us all: “Follow me.”

Let us turn now to the visual narrative that speaks so vividly of Andrew, Peter, and the Messiah whom they faithfully served—until the very end, when they were honored with a death resembling that of their Lord and Master.

We see immediately that this is no ordinary fishing scene; rather, it puts us face to face with the miraculous. There is no empty space in the depiction, for the divine presence pervades even the air surrounding the apostles, made visible by the curling gold acanthus leaves, which symbolize eternity and resurrection. These gold leaves seem to move towards the chosen fishermen, washing over them and breathing life into them as the breath of the heavenly Father does in Genesis, or as the Holy Spirit does in baptism, or as the incarnate Son does at the tomb of His friend: “Lazarus, come forth! And he that was dead came forth” (John 11:43–44). Notice how Christ—wearing the red robe of His Passion, and marked as divine by the cross in His halo—beckons to Peter and Andrew with His right hand, and clutches the book of Scripture in His left: He is the Word of God, He speaks the words of God, and all that He is and all that He says are fundamentally a calling forth from the tomb of a drab and worldly and self-centered life: “Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men.”

This passage from the Gospel is striking in its immediacy, and the illuminator has certainly captured this sense. The boat is not yet ashore, and Christ is already beginning to walk away—a visual detail that eloquently translates the evangelical urgency of Matthew 4:17: “From that time Jesus began to preach, and to say, Repent: for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.” It is in the very next verse, Matthew 4:18, that the Master, “walking by the sea of Galilee, saw two brethren, Simon, which was called Peter, and Andrew his brother, casting a net into the sea.” Other details in the image heighten this sense of urgency: water splashes against the bow, the brothers’ gazes are fixed on Christ, and a conspicuous triad of elements—two oars and a net—are swept back by the swift movement of the boat, which seems to be propelled more by the grace of God than by the strength of men.

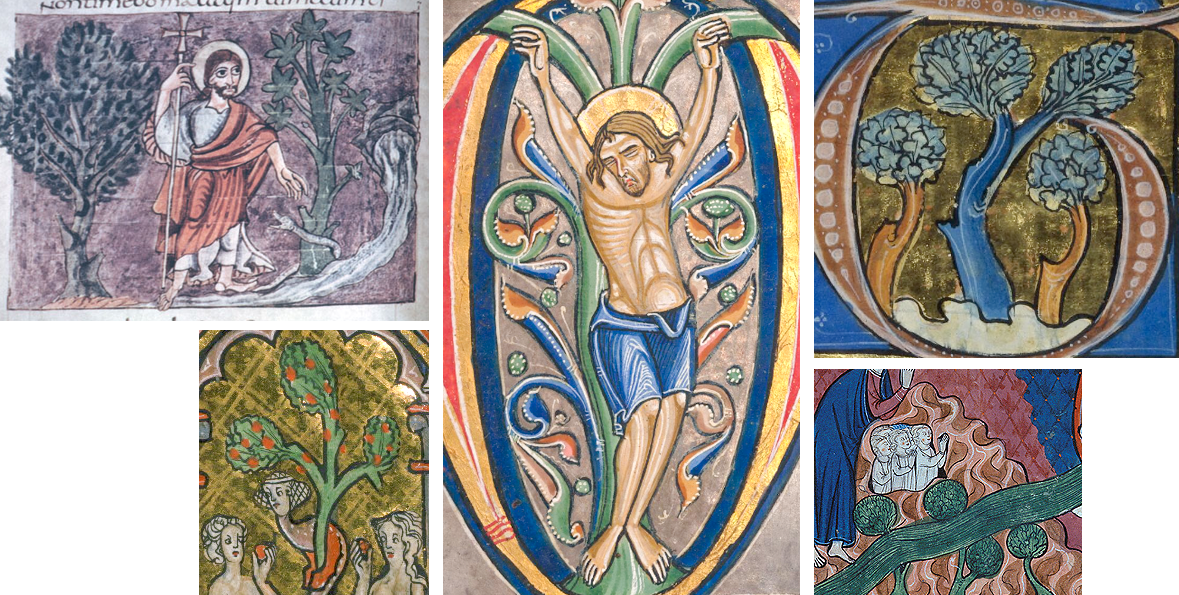

Finally, between Christ and the apostles we find a mysterious plant, seemingly sprouting up from the barren rock. Perhaps an obscure detail at first glance, the plant may actually be the thematic key to the entire composition.

The green branches and leaves stand out strongly against the golden background, and furthermore, the color green appears nowhere else within the rectangular blue frame that separates this scene from the rest of the page. In other words, the plant strongly attracts the viewer’s eye, which suggests that the artist wants its significance to strongly attract the viewer’s mind. What might this significance be? Given the context and its resemblance to depictions found in other medieval sources (a few of which are shown below), we can propose that this plant is the Tree of Life.

In medieval artistic and spiritual culture, the Tree of Life was a mythological life-giving tree that acquired associations with the Garden of Eden, the heavenly paradise (via Revelation 22:1–2), and the Cross of Christ. It was thus an especially rich and evocative symbol in which multiple streams of meaning converged upon the very theme that we have emphasized in this essay: the outpouring, mediated by the divine Word, of material and spiritual life. In the St. Andrew’s Day illumination, the artist placed the Tree of Life between Christ and the apostles, where it serves as a life-giving bond between the Master and the faithful servants whom He has called—it is, so to speak, in the very midst of that momentous encounter where He said to Peter and Andrew, “Follow me,” and they followed. All three labored to restore to humanity that fullness of life which we had in Eden; all three led souls to the glories of heavenly life; and all three died on that tree of agony which only Christians are bold enough to embrace as a Tree of love and life everlasting.

The cross appears again in one of the decorated initials, from which Andrew, with his iconic wild hair and long beard, emerges. He holds the cross of his martyrdom, inviting us to ponder where the call of Christ led him. With the night sky behind him, he looks not at the reader. Rather, he gazes from heaven, meditating on the Word of God, and on his humble fisherman’s life, now fulfilled and exalted and joyful beyond all imagining.

The other striking figure in the scene is the third person in the boat, who lacks a halo — his gaze is cast down and a hat is covering his eyes. Somehow he fails to hear the call and look up. Lots to ponder in that.

What a wonderful illuminating article. Thank you for your joy in sharing your work and thoughts.