I pray you all give your audience,

And hear this matter with reverence,

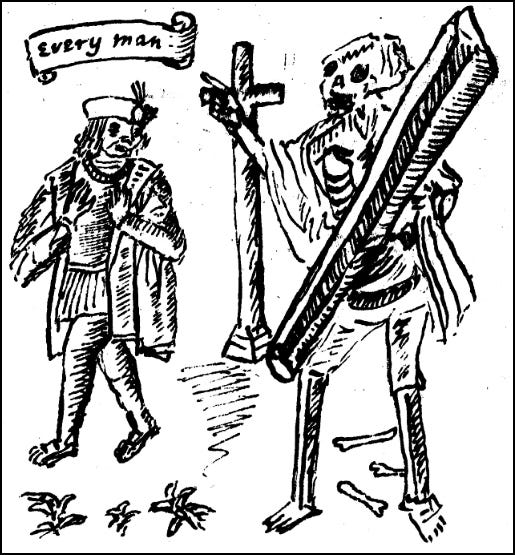

By figure a moral play—

The Summoning of Everyman called it is.

…

Ye think sin in the beginning full sweet,

Which in the end causeth thy soul to weep,

When the body lieth in clay.

Here shall you see how Fellowship and Jollity,

Both Strength, Pleasure, and Beauty,

Will fade from thee as flower in May.

Thus begins the morality play known as Everyman. The opening speech is delivered by the Messenger, and indeed, the author was not shy about his principal “message”: death and judgment comes for us all, so get your act together, before it’s too late. Whatever Shakespeare the dramatist may have learned from morality plays, his gift for thematic subtlety seems to have originated elsewhere.

Morality plays grew from the same cultural soil that produced the mystery plays, and like a mystery play, Everyman exhibits that curious medieval blend of reverence for and familiarity with divine realities. After Messenger finishes his introduction, the Almighty comes on stage. A modernized edition would indicate, “Exit Messenger. Enter God.” In the printed version of 1528, the stage direction is simply, “God speaketh.”

I proffered the people great multitude of mercy,

And few there be that asketh it heartily;

They be so cumbered with worldly riches,

That needs on them I must do justice.

The speech concludes with God summoning Death, who enters and says, “I am here at your will, / Your commandment to fulfill.” Interesting, isn’t it, to think of death as God’s servant? He tells Death that it is time for Everyman to make his “pilgrimage” into eternity, and Death sees the poor mortal walking, yonder, as if everything is fine, because “his mind is on fleshly lusts and his treasure.”

Death comes—quite literally—for Everyman, but the latter declares that he is not at all prepared to die and give an account of his life: “Full unready I am such reckoning to give…. O Death, thou comest when I had thee least in mind.” He offers, quite unwisely, to make Death a handsome payment if he will “defer this matter till another day.” Death explains that he doesn’t take bribes. Everyman asks for a delay of twelve years, to get his “counting book” in the “clear, / That my reckoning I should not need to fear.” Ignoring the outlandish proposal, Death informs Everyman that he can “cry, weep, and pray” all he wants, but it will avail him nothing: “the tide abideth no man.” Getting desperate, Everyman asks for just one more day: “Now, gentle Death, spare me till tomorrow.” Nope—“gentle” Death plays by his own rules, and all Everyman can do is make the most of whatever time remains to him:

See thou make thee ready shortly,

For thou mayst say this is the day

That no man living may scape away.

We don’t use the term “everyman” in normal conversation, so let’s make sure we’re all on the same page here. Who, exactly, is Everyman?

You are.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Via Mediaevalis to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.