Married Life in the Middle Ages

The essence of marriage hasn’t really changed; some important aspects of it most certainly have.

The Oxford Dictionary of Cultural Anthropology defines marriage as “a formal, socially recognized union between individuals that leads to stable domestic relationships involving a variety of rights and obligations, especially the sharing of labour, resources, and responsibility over children.” I find this definition noteworthy in two ways. First, it reminds us that marriage, as a basic social or anthropological institution, has been surprisingly uniform across the diverse cultures of the world and the various epochs of history. Second, it highlights the astonishing originality of Christianity, for which marriage—even when husband and wife are the two poorest peasants of the smallest, most forgotten village in the European hinterlands—is so much more than a formalized domestic alliance involving certain rights and obligations. In the Christian tradition, marriage is also a principal source of divine grace for individuals and communities, and a sacred bridge joining the material and spiritual realms, and even a living icon of the sacrificial love between the incarnate God and the vast society of His faithful servants on earth.

As we discussed on Sunday, some medieval writers were overzealous, or worse, in disparaging the married state and vilifying human sexuality, and the era’s ecclesiastical culture strongly favored the ideal of virginity over the fleshy reality of the conjugal union. At the same time, however, the extraordinary theological and poetic richness of Christian matrimony is largely the result of spiritual and doctrinal developments that occurred during the Middle Ages. We’ll return to this paradoxical relationship with marriage, and to the paradoxical qualities of marriage itself, on Sunday. Today I want to focus on practicalities, which are interesting in themselves but also interwoven with the loftier issues that pertain more directly to modern life.

There is something we must keep in mind as we consider this information about medieval marriage (and really any other historical information, but marriage, being such an intimate and deeply personal and intensely emotional experience, is a special case): since the day when Adam and Eve first sinned, human nature has not fundamentally changed. Indeed, a signal benefit of studying pre-modern literature, from the Bible and the Classics to the great works of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, is that one discerns the remarkable continuity, over time and space, of the human experience. Medieval husbands and wives belonged to a world that differed from ours in many ways, and some of these differences were extreme. But their hearts and souls were human, as ours are. They felt and suffered and hoped and dreamed, as we do. If we look past the accidents and search out the essence, we will find that what they feared, we fear; what they desired, we desire; what they loved, we love.

Medieval marriage could, in theory, begin at an age that for most of us is unimaginable: twelve for a girl, fourteen for a boy. These ages were stipulated by canon law, meaning that they were international in scope, but they were also minimums which local laws or customs, especially in northern Europe, might supersede.

Perhaps our modern instinct is to assume that boys and girls were just very different back then—shorter lives, earlier maturity, vastly harsher childhood, etc.—and that’s why they could get married at such a young age. My study of both history and literature makes me think otherwise. I’m inclined to believe that a twelve-year-old girl in the Middle Ages was much the same as a twelve-year-old girl today, or at least as a twelve-year-old girl of the pre-smartphone era. They could endure the burdens and responsibilities of marriage because their community supported them and helped them to actualize innate potential that still exists but nowadays remains latent until later in life.

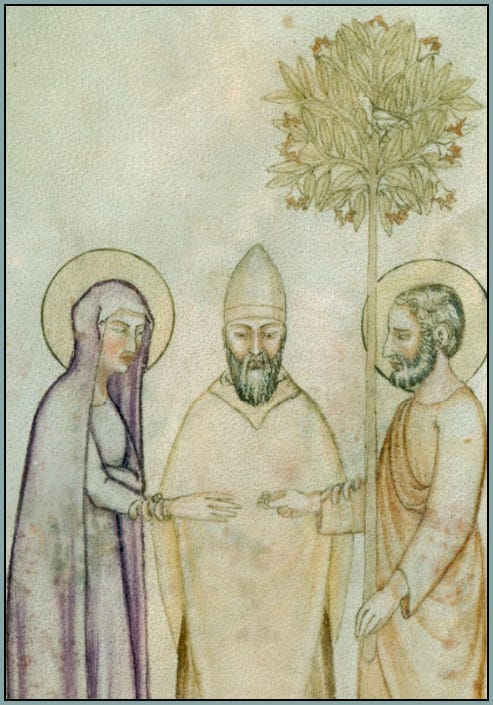

Furthermore, medieval people themselves were apparently quite skeptical of twelve-year-old girls or fourteen-year-old boys getting married. In northern Europe, first-time spouses were usually in their early or mid-twenties, with the husband being perhaps a few years older than the wife. I’m enchanted when I imagine a twenty-year-old Germanic bride, resplendent with youth and agrarian vigor and every wedding-day adornment that her village could supply, joining hands with her enamored twenty-four-year-old suitor, heart about to melt and knees weak under the weight of his euphoria. Will the honeymoon last? Of course not, but that’s beside the point—earthly pleasure is always fleeting. If we spend more time savoring it than taking pictures of it, we’ll have memories that give pleasure for many a year, and if we’re not too busy grasping at it, we’ll find that it’s just making way for something new.

In Italy, girls were likely to be married by eighteen, and their husbands might be closer to thirty. It would be a very large mistake to assume that because those men lived in a thoroughly Christian society, it was easy for them to behave themselves from puberty until the wedding night. Unfortunately, it appears that in many cases good behavior wasn’t really expected. It is a grave and fundamental problem of postlapsarian humanity that sexual desire arrives so long before marriage does. No one seems to have a particularly successful answer to this one. The Christian answer—prayer, virtue, assiduous continence, painstaking avoidance—is effective and highly beneficial for one’s long-term happiness, but historically it has not been overwhelmingly popular.

Perhaps to a surprising degree, the structures and ceremonies surrounding medieval marriage have survived, in some form, into modern culture. An example of a feature that has largely faded away, and I consider the loss a lamentable one, is the betrothal. Our current practice of “getting engaged” doesn’t make a lot of sense to me—engagement periods vary widely, the actual difference between a significant other and a fiancé(e) is unclear, and the engagement itself seems to have no contractual force. In the Middle Ages, betrothal was a solemn and legally binding event in which the man and woman publicly declared their intention to marry. This seems to me like a valuable means of sobering up young lovers before they tie the lifelong knot: a rash or foolish betrothal is bad, and may seriously complicate your life, but it’s not as bad as a rash or foolish marriage, which just might ruin your life.

And speaking of that lifelong knot: divorce did not exist in the Middle Ages. It did not exist in theory, and to a remarkable degree it did not exist in practice. As is still the case in the Catholic Church, marriages could be declared null—i.e., declared to have never existed—if an impediment to valid matrimony was identified. One common impediment was consanguinity, and the issue of consanguinity was a complex one. Presumably we can all agree that the medieval Church was wise to prohibit incestuous unions, but “incestuous” has no inherent definition, and originally the prohibitions on consanguineous marriage reached out so far into the extended family that they became a threat to marriage—as medieval historian David Nicholas explains, the early-medieval law against incest “made it possible for virtually anyone to annul a marriage by finding a common ancestor.” In the early thirteenth century, the Church redefined incest as marriage within four degrees of consanguinity instead of seven. This seems to have struck the right balance, but the highly interrelated nobility still had difficulty fulfilling the requirement.

The only recourse for spouses who simply disliked each other was legal separation, known as separation “in bed and board.” Ecclesiastical courts rarely approved such separations, which were socially disruptive and probably viewed as something approaching a spiritual death sentence: the separated spouses were still married, and therefore any sexual activity involving a third party was adultery. The Church had no illusions about the likelihood of an ordinary layperson leaving his or her spouse and then practicing strict celibacy for the next five or ten or forty years.

Though divorce did not exist in the Middle Ages, we should by no means imagine medieval society as a place where everybody was married to the same person from young adulthood to old age. Second marriages were common, not because of divorce but because of death: At certain times and in certain segments of society, plague and famine led to a relatively large number of widows and widowers, and medieval wives were more likely than modern wives to die in childbirth. We should be careful not to exaggerate these causes of mortality, though, especially among the hardy peasantry, who accounted for a large portion of the population and a small portion of the surviving records. Perhaps the leading cause of widowhood was simply the disparity in age between spouses; in the south, even a woman’s first husband might be a significantly older man, and in the north, second marriages often involved a large difference in age. Medieval Christians knew that lifelong marriage was obligatory when possible, but they also were well acquainted with the work of the Grim Reaper—how many, I wonder, really expected to marry only once?

The medieval Church, to her everlasting credit, developed a matrimonial theology that insisted upon consent: if one or both partners exchanged vows against their will, the marriage was not valid. In addition to the theological import, there is a quiet beauty in this doctrine, which seems to tell the bride and groom, “You don’t need to fall in love in order to get married, but you do need to be willing to fall in love.” To borrow a phrase from the Christian novelist Janette Oke, sometimes love comes softly.

Nevertheless, most medieval marriages were at least partially arranged, with the choice of spouse being more of a joint decision between parents and children, and with financial or political calculations also coming into play. In an environment like this, it would be difficult to idealize marriage as a passionate, amorous quest for one’s dream-fulfilling soulmate—and maybe that’s a good thing. In the words of one scholar, medieval marriage was probably perceived “as a kind of job” that offered the possibility of “love and mutual affection.” I find that striking, because it so accurately captures what my (very modern) experiences have taught me about the day-to-day reality of (a very modern) marriage: married life is hard work—duties, privations, labors, compromises, sacrifices—that in no way excludes the delights of love and mutual affection.

"Nevertheless, most medieval marriages were at least partially arranged, with the choice of spouse being more of a joint decision between parents and children, and with financial or political calculations also coming into play." Such a statement indirectly speaks about two absolutely opposed types of "love:" (the Medieval, i.e. true Catholic) one who was wisely oriented by the intellects (enlightened by the Supernatural Faith) of those involved in a matrimonial decision, and one - "passional," "carnal" love - based on the ephemeral impulses of the flesh without any implication of the intellect (i.e., reason).

Very interesting.