“Michael, of Celestial Armies Prince”

Join us for an artistic, poetic, and theological journey through an extraordinary twelfth-century painting of St. Michael the Archangel.

It was my pleasure to co-author this article with Amelia Sims McKee, who writes the excellent Substack newsletter Art for the Liturgical Year.

The Stammheim Missal, produced in the twelfth century at a Benedictine monastery in northern Germany, is a masterpiece of medieval art and a fascinating vision into medieval thought. The monastery was founded by the Saxon-nobleman-turned-bishop St. Bernward (960–1022) and inherited the rich cultural legacy of the Holy Roman Empire. It was renowned for artistic excellence, and its church, built just outside the walls of Hildesheim in the early eleventh century, survives to this day as a fine example of Romanesque architecture. It was dedicated to St. Michael the Archangel on his feast day, September 29th, in the year 1022. A thousand years later, we still marvel at the grandeur of this seemingly eternal structure built for the worship of the eternal God, and we still admire artwork created by monks who sang their prayers within its mighty walls. Their names are long forgotten; their mysterious visual poetry endures.

As a service book containing liturgical readings and prayers, the Stammheim Missal is like many other manuscripts produced during the Middle Ages. As a work of profoundly theological and stylistically captivating visual art, it is simply extraordinary—a unique expression of medieval spirituality and artistic culture.

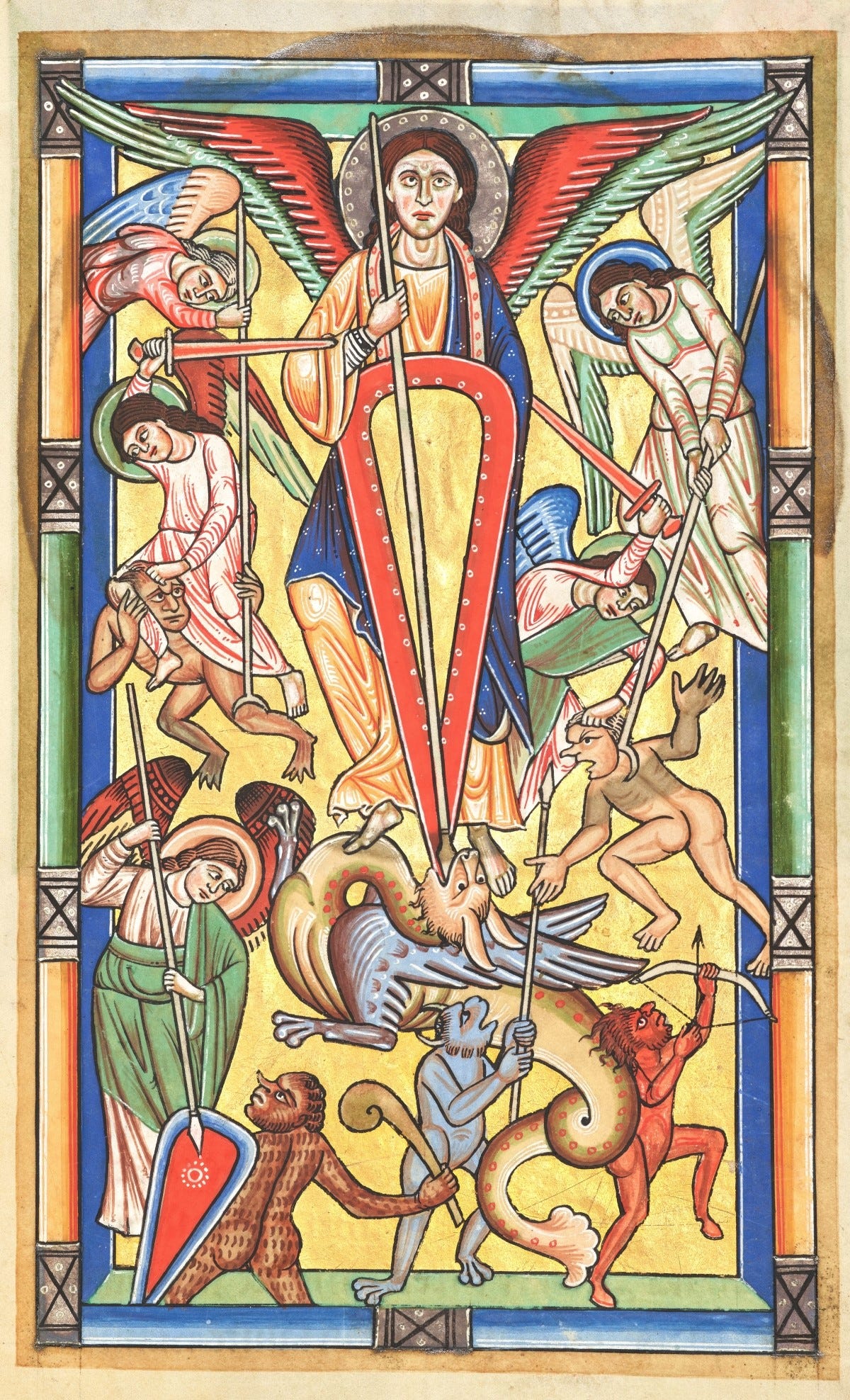

Today we’ll explore the miniature that introduces the variable prayers for the holiday known in English as Michaelmas, an ancient feast honoring St. Michael and other members of the angelic host. In the Middle Ages, it was a holy day of obligation, meaning church attendance was required, and it served as the liturgical centerpiece for a rich corpus of harvest celebrations and folkloric customs.

The illuminator created an image that both delights the viewer and inspires a fearsome confidence in the immaterial spirits who surround the throne of God and bring His divine aid to the children of men. The painting depicts the battle between angels and the forces of evil, with Michael casting down the dragon of which the Scripture speaks:

And war broke out in heaven; Michael and his angels fought against the dragon…. The great dragon was thrown down, that ancient serpent, who is called the Devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world—he was thrown down to the earth, and his angels were thrown down with him. (Revelation 12:7,9)

As the Stammheim painting reminds us, this scriptural imagery of St. Michael vanquishing and casting down a dragon has powerfully influenced Christian art: the archangel’s iconographic archetype consists of a winged, armed warrior standing above a defeated fiend. In more recent depictions the fiend is often anthropomorphic, but given the preference for expressive and symbolic modes in Romanesque art, we shouldn’t be surprised that the Stammheim illuminator portrayed Satan as a dragon.

The word that appears in the Book of Revelation is Greek drakon, which in the classical era meant simply “serpent” but may often have referred to the sort of serpents that any reasonable person would be very worried about, as in Book 2 of the Iliad:

enth᾽ ephanê mega sêma: drakôn epi nôta daphoinos / smerdaleos

then appeared a great sign: a serpent, on the back blood-red, / a thing of horror

In the first century AD, when Revelation was written, drakon suggested a malign creature evoking both mythical monsters and the satanic serpent of the Eden narrative. In medieval culture, the biblical drakon, or draco in the Vulgate’s Latin, merged with the various serpentine, winged, fire-breathing, poison-spitting, man-slaying, elephant-strangling, treasure-hoard-guarding beasts that had long circulated through Indo-European mythology and folklore. The culmination of this ancient and mysteriously widespread collection of dragon literature bears the mark of divine Providence: defeating a physical dragon became the defining act of heroism in medieval epics and Romances, just as defeating the spiritual dragon—symbol of noxious vice, monstrous tempter, sinister icon of evil itself—was a defining act of holiness.

The angels in this image are a far cry from the chubby cherubs of Renaissance art. They confidently wield human weapons, and their visual form resembles the adult human body in all but the wings. Their facial expressions convey serenity amidst the pandemonium—from Greek for “all demons”—of this monumental contest between the forces of good and evil.

One angel even has a trace of sorrow in her gaze, as though affected by the deformity and degradation of a being who was once as splendid and noble as she was:

Michael’s unique halo, blue robe, and imposing figure set him apart from the other angels, emphasizing that he is their general and leader. Among the figures, the archangel shows an exceptional peace, not even bothering to glance at his opponent—the victory of the Almighty is not in doubt. His furrowed brow suggests intense concentration, and his eyes tilt upward, reminding us that he is ever obedient to the Lord Most High. Indeed, his whole being seems to ask the very question that is his name: who is like God? This humility perfectly contrasts with the pride of Lucifer and declares that topsy-turvy logic of the kingdom of heaven: God uplifts the lowly and casts down the haughty.

Furthermore, it is in his humility that Michael resembles Christ. His cruciform posture and triumph over the dragon recall a Carolingian crucifixion motif, where Christ is shown on the Cross with the serpent at His feet.

Michael, in the center of the action, symbolizes divine justice, and his confident stance imparts order to the dizzying array of angels and demons battling around him. The luminous colors and harmonious arrangement of figures create a visual rhythm that gives the composition a sense of excitement but also of balance. By combining a dramatic narrative with a heavenly, symbolic view, the artist invites us to meditate upon the scriptural passage from Revelation—one of the liturgical readings for the feast—and upon Michael himself, alive and glorious among the saints in heaven.

While the army of demons appears grotesque and almost comical, Michael’s heavenly army projects an assertive gravitas. The demons’ and dragon’s contorted poses contrast with Michael’s victorious, upright posture, accentuated by his long face, lance, and shield. His seemingly effortless subjugation of the dragon beneath him inspires confidence in the angels and in God’s power to conquer sin and death.

Notably, Michael occupies space both inside and outside the frame. The sword of the angel in the upper left and the dragon below trap Michael in the frame while his overarching wings push him out of it, reminding us that angels, being spirits, are not bound by time or space. Here, Michael takes part in the battle but also oversees it as a commander. He fights in the Apocalypse as a warrior but also comes to help the faithful in their battle against evil. Likewise, we understand the Apocalypse as both individual and general. Every soul must face the personal Apocalypse of death and judgment.

Often, in more modern renditions, St. Michael appears preoccupied with his enemy. The medieval Michael of the Stammheim Missal, however, need not concern himself overmuch with the ancient serpent, who is a mere creature and as nothing next to the Creator. Instead, he looks upward to his God, the Lord of Victories, and outward to us, exhorting us to invoke him and his angelic comrades in the epic spiritual battle that we all must face and that Milton, in Paradise Lost, imagined so well:

Go, Michael, of celestial armies prince

And thou in military prowess next,

Gabriel, lead forth to battle these my sons

Invincible, lead forth my armèd saints

By thousands and by millions ranged for fight

Equal in number to that godless crew

Rebellious! Them with fire and hostile arms

Fearless assault and to the brow of Heaven

Pursuing drive them out from God and bliss

Into their place of punishment, the gulf

Of Tartarus.

Michael is one of my favorites. This was an interesting read and the interpretation of the art is helpful.

Love the commentary. Thank you!