The Albigensian Heresy Is a Cautionary Tale for Us All

The strange story of medieval Europe’s most prominent puritans

H. W. Crocker, with his characteristically punchy prose, described the Albigenses as “a sort of Pro-Death League.” They were, he explains,

opposed to marriage, children, and pregnancy (a calamity for which abortion was recommended); and if one could not follow a Pauline path of celibacy, the next best thing was fornication that did not perpetuate the species. Because matter was sinful—only the spirit was pure—death was to be hurried along. Suicide was accepted. The preferred Albigensian method was self-starvation supervised by helpful Albigensian hospice workers to make sure the loved one didn’t slip out for some bread and wine.1

He’s painting with a broad (and rather sensationalistic) brush here. Nevertheless, the resulting picture conveys how radical, and radically un-medieval, the Albigenses were, despite the fact that their heyday, in the High Middle Ages, coincided with the vigorous maturity of medieval culture. You may also have noticed that Crocker’s summary shines a spotlight on Albigensian practices that are eerily modern. There is much to be learned from a sect that fell deeply into modern disorders—centuries before modernity existed.

If you’re familiar with the Albigensian Heresy but never thought about it as a puritanical movement, part of the problem is that “Albigensian” is not the best way to identify the movement’s ideology. That word comes from Albiga, the Latin name for Albi, a town in southern France where the heresy was strong. A more informative term, which goes back all the way to the year 1163, is “Catharism.” The origin of “Cathar” is the Greek adjective katharos: “pure.”

And the connection is not merely a linguistic coincidence. During and after the Reformation, some writers recognized that the new Protestant puritans were not fundamentally different from the medieval Cathars. This seems to me not widely known; here are a few examples:

This name Puritan is very aptly given to these men, not because they be pure no more than were the Heretics called Cathari, but because they think themselves to be mundiores ceteris, more pure than others, as Cathari did.

—John Whitgift (d. 1604), archbishop of Canterbury…the ancient Cathari or Primitive Puritans.

—Thomas Fuller (d. 1661), Anglican clergymanThis rite of confirmation hath had the fate to be opposed only by the schismatical and puritan parties of old, the novatians or cathari, … and [by the] new cathari, the puritans and presbyterians.

—Jeremy Taylor (d. 1667), Anglican bishop of Down and Connor

That last passage is from a book with one of those long-winded titles that were popular back in the old days. Taylor acquired some fame as a prose stylist, and if you don’t agree with the content of his title, you might still appreciate its flair: “A collection of polemical discourses wherein the Church of England … is defended … against the papists on one hand, and the fanatics on the other.”

It’s hard to deny that the Albigenses, by medieval standards at least, were fanatics. Though they referred to themselves simply as “Good men” or “Good Christians,” the term “fanatic” may actually have appealed to them, since it derives from Latin fanaticus: “inspired (or perhaps more accurately, possessed) by a god.” After all, the Cathars must have imagined that their revolutionary doctrines were filtering into their minds from some sort of divine source. How else could they have discovered that the Faith of their ancestors, their clergy, their countrymen, and their culture’s heroes was—it turns out—nothing but a tangled, poisonous web of truth and error? How else could they have believed, and with such confidence, that there are two gods, one good and one of darkness, and that the world was created by the son of the god of darkness, and that the human body is actually a carnal prison for fallen angels, and that much of the Old Testament is not Sacred Scripture, and that the Incarnation was an illusion, and that Christ was not the Redeemer? How could medieval Europeans from Christian lands so audaciously mutilate medieval Christianity? They must have been “inspired” by something.

As we saw last Sunday, the traditional wisdom of the West tells us that too much melancholy—or, we might say, too much puritanical gloom and severity—can lead to “frenzy.” It’s interesting to note that one translation for Latin fanaticus is “frantic, frenzied,” since that’s what happens to you when you’re inspired by a Greco-Roman deity, rather than by the Christian God of peace and loveliness. And if we are to judge from the history of the Cathars, it’s also what happens when you’re inspired by the “spirit” of puritanism.

Catharism was not a carefully developed, unified belief system. In fact, that was one of the arguments used against it: the welter of Cathar doctrines and myths was a sorry sight next to the unity and coherence of medieval Christianity. But extremist ideologies, even when their doctrines are disorderly and unattractive, have a way of finding adherents.

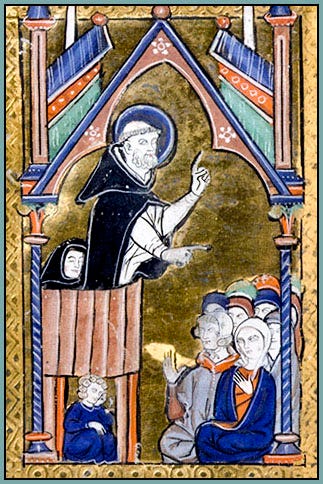

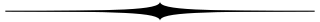

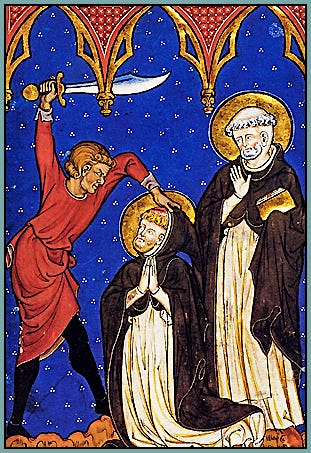

Catharism mostly spread by word of mouth. To be fair, some of the converts were legitimately impressed by the ascetic manner and apparent holiness of Cathar preachers, who must have looked rather saintly when compared to the less-edifying members the Church’s hierarchy—alas, the age was not immune to the malady of worldly, corrupt, immoral clergy. However, one can also imagine simple folk in the towns and villages being manipulated and exploited by smooth-talking, self-serving, semi-delusional “Perfects” who wanted a larger group of “Believers” to support and admire them. That, by the way, was how the Cathars divided themselves into two spiritual categories vaguely equivalent to priests (or monks) and laity: there were Perfects, and there were Believers.

But what about those at the other end of the sociopolitical hierarchy? The Albigensian movement would have died quickly if it had been energetically opposed by the secular authorities. Why was it tolerated and even protected by feudal lords—that is, by people of higher social standing, with more education and stronger ties to orthodox clergy? It’s the usual answer: radix malorum cupiditas est, or as the King James Bible has it, “the love of money is the root of all evil.” The aristocracy of southern France used the Albigenses as a club to wield against their temporal rivals, namely, the Church and the French king:

For the southern nobles, the issues involved were not doctrinal. They could not have cared less that the Albigensians denied the Trinity or the Virgin Birth or that they dismissed the whole panoply of Church custom as superstition. Nor, for that matter, did the nobles care that the Albigensians were economic communists…. The real issue was who would rule and who would gain the wealth of the land.2

How beautiful it is, when those of noble blood are also virtuous. How ugly, when they are not.

So a Cathar was either one of the Believers or one of the Perfect. Believers, who lived in the world and worked ordinary jobs, provided food and lodging for the Perfects and were expected to attend their sermons. They were permitted to marry, and even to have children, but childbirth must have been a dreary affair in Cathar households, since Catharism condemned procreation as a lamentable practice that leads to yet another soul being imprisoned in an evil body. Also, believers had limited access to Cathar theology, which I find interesting—it’s as though the elites knew that medieval peasants, generally traditional and commonsensical, would look seriously askance at all this business about two gods and an evil Creation.

The Believers could become Perfect through the ritual of consolamentum, which guaranteed salvation, and which many folks must have delayed as long as possible, since it entailed the renunciation of earthly pleasures: the Perfects embraced poverty and celibacy while abstaining from meat (because it might contain the soul of a fallen angel); from milk, eggs, and cheese (because they result from, or in the case of eggs are closely associated with, reproductive activity); and from wine (I’m not sure why, I guess because it tastes good).

Historians tend to mention these things as if theory and practice were more or less the same, which is fine when the scanty surviving records don’t provide clear evidence to the contrary, but a literature guy like me—head filled with stories of every imaginable human failing—has learned to see the situation rather differently. Celibacy, for example, isn’t the sort of thing that just happens because you want it to, and the Cathars abandoned the ecclesiastical social structure that helped Christian priests and monks to keep their vows. As far as I’m concerned, they had also abandoned the grace of God, since they believed that the institutional Church was the Church of Satan. Thus, I hope I’m not being too cynical when I suggest that some of those Cathar “Perfect,” after looking a bit too long at a nicely proportioned young lady, decided that the human body wasn’t so evil after all.

The Cathar heresy has stirred up quite a bit of debate among modern historians. One unresolved issue is the movement’s origin, which for some was a “dualism emanating from the Balkans,” and for others was “anticlericalism and the enthusiasms of the Gregorian reform [of the eleventh century].”3 For my purposes, though, the origin is clear enough: Catharism is an outgrowth of the puritanical urge, which, as we discussed last week, inheres in human psychology and perhaps was causing problems for the human race even in the Garden of Eden.

It’s possible to portray Catharism in an extremely negative light, as Crocker does. It’s also possible to drift toward a (somewhat) more sympathetic portrayal. But it seems to me well-nigh impossible to make the Cathar religion look good, or even tolerable. I can imagine that some medieval adherents saw it as a means of “punishing” the Catholic Church for some perceived grievance—maybe the parish priest sold someone a sick horse, or a bishop flaunted his wealth during a bad harvest season, or a delinquent monk started flirting with someone’s wife. But for people who don’t have a perverse motivation of this kind, and who know what Catharism actually is, the religion is likely to appear insufferable at best, and repulsive at worst.

Thus, for those who are concerned that Christianity not in any way resemble a religion as unappealing and repressive as Catharism, it’s worthwhile to consider the essence of this heresy. And its essence was this: the material world, which includes the human body, is evil. If this sounds outlandish, we must remember that we might sometimes act as though this notion is true, even if we don’t consciously believe it and would never directly affirm it. The puritanical urge is insidious, and I will conclude with a quotation that appeared also in last Sunday’s post, and which was written by a brilliant Norwegian woman who had immersed her mind in the culture of the Middle Ages:

The Catholics of America have been infected by the puritanical system of suppression—which is entirely un-Catholic.

—Sigrid Undset (d. 1949), essayist and Nobel Prize–winning novelist

H. W. Crocker, Triumph: The Power and the Glory of the Catholic Church. Three Rivers Press (2001), pp. 170–71.

Ibid., pp. 171–72.

See Deborah Shulevitz, “Historiography of Heresy: The Debate over ‘Catharism’ in medieval Languedoc.”

While folks have debated just how much the Cathars are a medieval variant of the Gnostics, I do think it’s significant that they arise as a movement that is historically situated. Their identification of the Creator God with Satan is both an extreme reiteration of the Marcionite heresy, and at its core, a renunciation of the Eucharist and belief in the Covenantal love of God. The Jewish understanding was that the good Creation awaited the fullness of the eighth day. The liturgy is the announcement of divine fidelity and the ultimate transformation of the world of dust, sin, and death into the Resurrected Body of Christ.

And so, when I look at modernity and try to discern the imprint of the Cathars, I suppose the expert technocrat is a kind of Perfect, whose gospel is the transhumanist dream of translation into AI, liberated from the constraints of created finitude and the doom of mortality. And then the parallel to the alliance of Puritanism with indulgence of hedonist abandon is the virtual world, both a flight from the incarnate flesh, and equally a realm where every form of the illicit and perverse is celebrated, because the digital promises a false infinite and idolatrous eschatology.

The Puritans of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries were very different in many ways from the Albigenses or Cathars of the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. As the word itself indicates, they wanted to continue the so-called Reformation and purify the Anglican Church of all the remnants or traces of Catholicism, especially regarding certain liturgical practices. They despised Roman Catholics and the Roman Catholic Church, but they did not despise the created world. The Puritans of the Elizabethan and Jacobean ages enjoyed good food, good drink, good company, good marriage, procreation and almost everything else just as much as any of their contemporaries.