The Medieval Year: How to Read a Medieval Calendar

And for our end-of-August celebration: the most beautiful harvest poem I've ever read.

The Medieval Year, a weekly feature of the Via Mediaevalis newsletter, gives us an opportunity to appreciate calendrical artwork from the Middle Ages, reflect on the basic tasks and rhythms of medieval life, and follow the medieval year as we make our way through the modern year. Please refer to the first post in this series for more background information!

We’re still in August, month of the grain harvest, and since we’ve already spent a few weeks on this topic—with posts on barley-houses (i.e., barns), the long hot days with sickle and flail, everybody’s favorite late-summer festival, and the art of thatching—we’ll take this opportunity to learn about reading a medieval calendar.

Let’s return to the lovely August calendar page found in the Hours of Henry VIII:

As regular readers of The Medieval Year will already know, the page is divided into the calendar itself and the depiction of the labor of the month. The calendar section contains various elements that are common to medieval calendar designs. First, we have the enlarged, embellished “KL”:

This stands for “kalends,” a word derived from Latin kalendae and meaning the first day of the month. Here are two more examples:

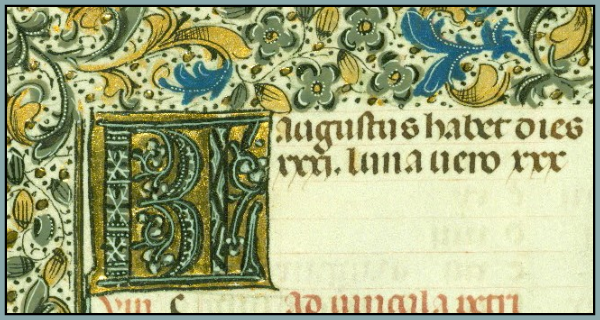

To the right of the “KL” is some cryptic information written in Latin and Roman numerals:

The first line says, in highly abbreviated form, Augustus habet dies xxxi, which means “August has 31 days.” The next line says Luna xxix, meaning that this lunar month has 29 days. Here’s an example in which the lunar month for August has 30 days:

Lunar months have either 29 or 30 days, and in theory, they add up to 354 (solar) days, which is the length of the lunar year (one lunar cycle is about 29.5 days, and 29.5 × 12 = 354).

In a world that lacked printing-press technology and inexpensive paper, calendars needed to last a whole lot longer than one year. The medieval manuscript calendars that we’re discussing were designed to be “perpetual,” meaning usable for many years. This is the main reason why we modern folks find them so baffling—you need specialized techniques to make a calendar perpetual. We see these techniques in action to the left of the feast-day descriptions:

The letters are called dominical letters. Notice there are seven, “a” through “g,” just as there are seven days in the week. The dominical letters tell you which days in a particular year will fall on a Sunday. So if you’re in a “c” year, for example, you know that the days marked “c” in the calendar will be Sunday, and the other days of the week are then easily determined with reference to Sunday. The letter changes at the end of the year, and also on February 25th in a leap year. (If you’re curious, 2024 was a “g” year before the leap day in February, and now it’s an “f” year.)

The Roman numerals to the left of the dominical letters are called golden numbers, and they include numbers 1 through 19. Here’s another example:

The golden numbers are the most complicated part of a medieval calendar. As mentioned above, the lunar year is shorter than the solar year (by 11 days), and thus the two cycles are out of sync. It turns out that they resynchronize every nineteen years (a period that corresponds to 235 lunar cycles). This means that the new moon can fall on 20 different days in the month, and that’s what the golden numbers indicate: if you know the golden number for the current year, you can use the calendar to find the date of the new moon. According to the calendars shown above, the golden number for 2024 is 13, but according to the standard calculation method, we’re currently in golden number 11. I’m reaching the limits of my calendrical knowledge here, but I’m assuming that the discrepancy is due both to imperfections in the golden-number system (which were a known issue in the later Middle Ages) and to the loss of ten calendar days that occurred when the Gregorian reform was implemented in 1582.

We’ll conclude with a selection from my favorite poem about the grain harvest and, more generally, about the beauty and wholeness of traditional agriculture. It was written many years ago by a Hebrew poet, and it had the honor of being included in the world’s most famous book. It has come down to us as the sixty-fifth Psalm. I’ve included a recording that gives you an idea of how this English version might be sung.

Thanks for the explanation of the letters, I've never understood what they meant!

I’ve just found you. I am very nerdily excited for what I will find here.