The deep and mysterious story of mankind’s relationship with pain begins in the Book of Genesis. Indeed, rarely has any poet, philosopher, or sage pondered a deep and mysterious thing whose story is not somehow told in Genesis.

Unto the woman he said, I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children…. And unto Adam he said, … cursed is the ground for thy sake; in toil shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy life.

Man and woman have sinned, and pain is promised to each: the labors of the field for man, the labors of birth for woman. We read this as punishment, and rightly so, but we note also that the text itself does not use this word. “Unto the woman he said, … unto Adam he said, …” There is almost a sense that God is not so much punishing them as explaining to them the inherent nature of things: “Because thou hast hearkened unto the voice of thy wife, and hast eaten of the tree of which I commanded thee, saying, thou shalt not eat of it: cursed is the ground for thy sake…” Because you have sinned, there will be disorder, sadness, suffering: the earth shall yield thorns and thistles, and you shall toil, and your wife shall sorrow in bringing forth children—“till thou return unto the ground; for out of it wast thou taken.” The Old Testament scholar Dr. Herbert Ryle (d. 1925) offered thoughtful glosses on this passage:

The pains and disabilities of child-bearing, which darken the mystery of many a woman’s life, are declared to be the reminder that pain is part of God’s ordinance in the world…. Not man, but the ground for man’s sake, is accursed. Its fruitfulness is withheld, in order that man may realize the penalties of sin through the pains of laborious toil.

My point here is that the cause-and-effect relationship between sin and pain is a primeval relationship. It goes back to Eden and now inheres in the human experience in such a way that pain itself also inheres in the human experience. Personal sins certainly cause pain—oh, how dreadful the pains they can cause! But Christ committed no sin, and He suffered; His mother committed no sin, and she suffered; many saintly men and women lived lives of extraordinary rectitude, and they suffered. The harsh reality is that human life itself also “causes” pain. This is pain that “comes from the elemental knowledge of knowing you are alive,” as someone eloquently stated in a comment on the previous post. It is the pain of fullest joys, which cause us to weep, and of truest love, which the poets so often make a prelude to tragedy. Even Colin Clout, the rustic shepherd of Edmund Spenser’s eclogues, discovered the bitter pang of sweet love:

I love thilke lasse, (alas why doe I love?)

And am forlorne, (alas why am I lorne?)

She deigns not my good will, but doth reprove,

And of my rurall musick holdeth scorne.

The poor boy fell for Rosalinde, who was “a thousand” times his curse but “tenne thousand” times his blessing on that fateful day when he

saw so faire a sight, as she.

Yet all for naught: such sight hath bred my bane.

Ah God, that love should breed both joy and paine.

Since the Fall, pain is woven into the fabric of our world. We may fear it, we may hate it, we may flee from it, we may sigh and groan and rail against it—but it is part of what makes us human.

We began this story about pain in Sunday’s post, where I reflected on my recent illness, on the mystery of sickness and suffering in “a very modern medieval village,” and on Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, in which pain is no longer necessary because society has unlimited access to soma, “the perfect drug.” In Chapter Three of that book, someone describes the curious humanity that existed before people finally managed to build a brave and marvelously new world, a world where there is “no leisure from pleasure” and “not a moment to sit down and think.” Various quaint things are mentioned: things that to us may seem deeply, beautifully, gloriously human, and that used to exist before the apotheosis of industry and the suppression of poetry and the invention of soma. Huxley’s point here is not subtle: these are things that might cease to exist, or cease to be thought of, in a perpetually “pain-free” future.

“There were some things called the pyramids, for example.”

“Mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters, … husbands, wives, lovers. There were also monogamy and romance.”

“And a man called Shakespeare.”

“There was something called Christianity.”

“There was also a thing called God.”

“There was a thing called Heaven.”

That mortal man who hath more of joy than sorrow in him, that mortal man cannot be true…. The truest of all men was the Man of Sorrows.

—Melville, in Moby-Dick

Quite early in my adult life I had to come to terms with pain, and years later I had to come to terms with joy, and I eventually discovered that the two can coexist in a way that is so richly and poetically and mystically human that a world without such coexistence is a world afflicted by a gnawing darkness. The modern world is thus afflicted; the medieval world was not.

And when I say “discovered,” I don’t mean that I experienced or attained this coexistence. That’s the hard part. I mean that I have sensed it and observed it and contemplated it in diverse manifestations of medieval civilization, which is singularly attuned to the nature of earthly life as a mysterious and never-ending dance of joy and sorrow, feast and fast, leisure and labor, pleasure and pain. Imagine man and woman in the embrace of an elegant and intricate dance: how distinct the two partners, and yet how unified their steps; how different their bodies, and yet how complementary; how fixed their roles, and yet how easily they trade places; sometimes they move so swiftly and freely, with such grace and passion and devotion, that the two are as one—an illusion that, like paradox, speaks truth. And what goodness we see in one partner cannot endure without the other.

The medieval dance of joy and sorrow—the dance, that is, of human life—is not something that can be described in one short essay. It cannot be adequately described in many such essays, but an attempt must be made, and we will, therefore, revisit this topic in the future. Indeed, it is a topic that I personally plan to revisit regularly, in one way or another, until the dance has ended.

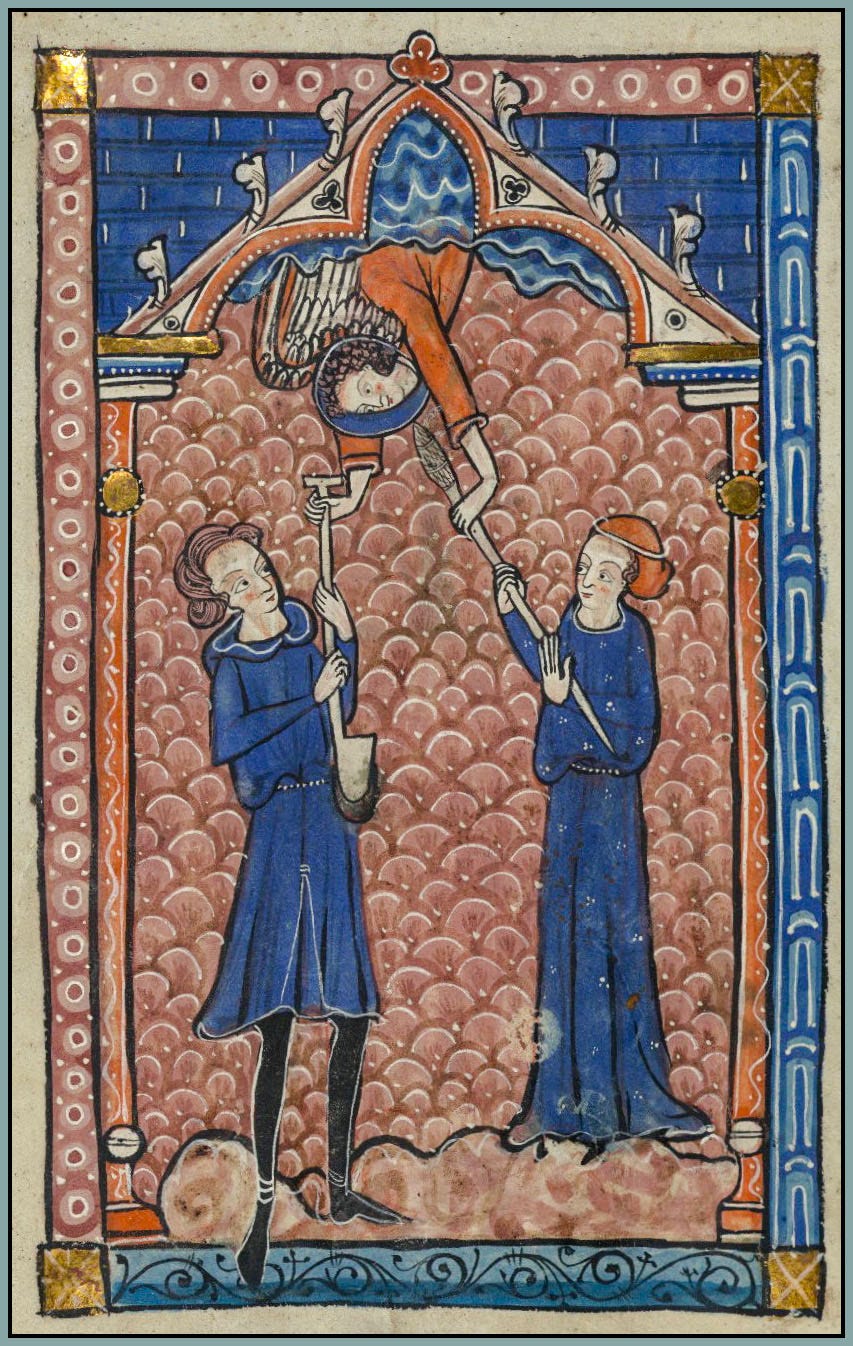

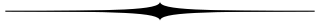

We will conclude with a few artifacts that begin to convey the cultural mentality of which I speak. The first one, a full-page illumination of Christ Crucified, is shown above. Does this not give us much to ponder? Is there not an arresting contrast between this image and so many other images of the Crucifixion produced in more modern times? Should we not ask ourselves pointed questions about the nature of pleasure and pain in a society that surrounds a gruesome murder—the death of God, the deathlike sorrows of His Mother, the consummate agonies of human history—with a border of vibrant colors, exquisite flowers, cheerful insects, and ripe strawberries?

Next we have a song that I shared with you some months ago—a simple old folk song, with a jovial melody, and which must have been a favorite among the lads and lasses of some rough-hewn village in the English Midlands. Its first words are “Merry it is…,” and its final words, which in terms of music sound the same as the rest, are “sorrow and mourn and fast.”

And then we have a lyrical treatise of spiritual romance such as A Talking of the Love of God, in which the dying Christ inspires both desire and horror, for He is both divinely beautiful and hideously desecrated, and in which the faithful soul longs for Him “as one that is mad with love, as one that is sick with the pain of love.”

Finally, I will leave you with the words, translated by Frances Beer from the Middle English, of Julian of Norwich, a fascinating anchoress and writer from late-medieval England who will surely be the subject of future essays:

Then the pain recurred, and then the joy and the gladness, then the one and then the other…. This vision’s purpose was to teach me the need for each soul to feel this way: sometimes to be in comfort, and other times to fail and be left alone. God wants us to know that he keeps us safe both in well and in woe, and loves us as much in the hard times as the good…. God freely gives pleasure when he chooses, and other times he leaves us in pain. Both are done for love.

I’m not sure how germane the following thoughts are but I wanted to share them in case they might be helpful to whomever reads them. I despise the experience pain and suffering, but strangely, I have learned to see it as a gift and to thank God for it. I do not seek it out except in little mortifications that are really just a bit uncomfortable and inconvenient at worst. But when my body hurts or my soul is in agony Jesus is giving me the opportunity to suffer with Him. Joined with His pain and suffering, mine becomes redemptive. Sometimes I offer it for a specific intention, but more often than not I give it back to Him to use as He wills and thank Him for the opportunity. The nuns used to call it “offering it up.”

Thanks for pointing out the cheerful summertime blooms and seeds in the margins of the somber crucifixion scene. It reminded me of how, when tragedy strikes, you think, "How can life go on as it was?" And then the birds sing and the fruits ripen on the tree. Such a paradox! Yet also very deep theologically, I think.