In the standard timeline of European history, the end of the Middle Ages is adjacent to the beginning of the Renaissance, an era with a French name that sounds somehow more impressive than its exact English equivalent, “rebirth.” Scholars are somewhat skeptical of “periodization” these days, so we have to ask: Did the Renaissance actually exist?

If you type that exact question into Google, its semi-delusional plagiarizing regurgitator (aka “artificial intelligence”) assures you that “yes, the Renaissance definitely occurred.” Then, almost as if Google’s software is “intelligent” enough to engage in self-mockery, the first search result is an article, written by a Medieval Studies professor at Virginia Tech, entitled “There Was No Such Thing as the ‘Renaissance.’” Here’s a highlight from that piece:

The “Renaissance” is nothing more than air, a myth created by 14th-century Italians to tell themselves they were different—better—than their ancestors. And the “Renaissance” survives to today because we find it comforting like a warm blanket.

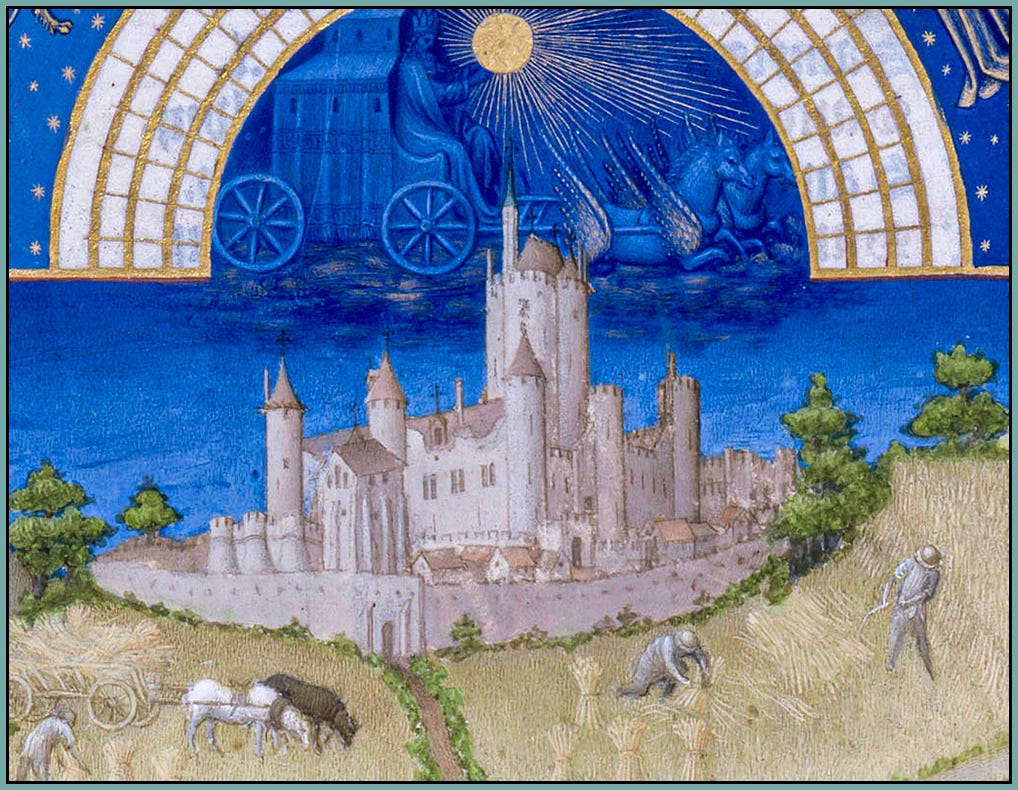

There is some truth in this. First of all, dividing up a civilization into nicely arranged eras and movements, like pieces of fabric cut neatly and sewed into a quilt, is always an exercise in oversimplification. Historical periods just don’t begin and end like that, especially when you consider the entire society rather than just the urban artists and intellectuals. Even in western Europe, agrarian folk in certain areas retained a medieval lifestyle long after the Middle Ages (and even the Renaissance) had supposedly ended.

Another problem arises when you consider the timeline. Notice how the passage above references “14th-century Italians.” So the Italians were having their Renaissance in the 1300s, and Shakespeare—writing in the late 1500s and early 1600s—was also a Renaissance poet? If the Renaissance was a rebirth, then Europe was in labor for a very long time! Actually, this is not so surprising if we accept the notion that cultural changes, like springtime (or hay fever), begin in the south and slowly migrate northward. But still, the Renaissance then looks like a collection of partially related local developments, rather than a monumental civilizational shift.

Finally, there’s no neutral terminology here. To call a certain period the Renaissance is to convey a value judgment about what existed before that period; to call a period the “Middle” Age is to convey another value judgment about the insignificance of a thing that merely happens in between two other things. And when one considers the blatantly (almost comically) propagandistic quality of a name like “the Enlightenment,” it’s easy to appreciate the more “non-judgmental” period labels found in academia, where the Renaissance is also “the early modern period,” and where you see terms like “the long seventeenth century” or “the long eighteenth century.”

Having said all that, I am more inclined (ah, the irony!) to agree with the Google regurgitator than the Virginia Tech professor: the Renaissance definitely did occur. And furthermore, because of what the Renaissance appears to have been, the fact that it occurred is important—indeed, crucial—for understanding ourselves, surviving our modern world, and shaping a better future.

Of course, historical periodization is imperfect; certainly, it requires oversimplification; but that doesn’t mean it’s useless or fundamentally inaccurate. Medieval civilization—vast, diverse, non-technological, religiously conservative—was not conducive to large-scale, (relatively) rapid cultural transformations. Nevertheless, such transformations can occur when there is a confluence of mutually reinforcing developments in the domains of philosophy, politics, economics, fine art, and spirituality. That’s what happened in the Renaissance, and there’s no need to lament the whole thing as some sort of neo-pagan self-worshipping catastrophe. In the long term I guess it didn’t work out too well, but then what about Caravaggio and Michelangelo? More and Erasmus? Byrd and Palestrina? Cervantes? Shakespeare? Machiavelli? (Okay, we could probably survive without that last one.)

My purpose here is not to defend the assertion that the Renaissance really happened. I’m not exactly going out on a limb by saying this—it’s still a perfectly mainstream perspective. I’ll give you one example, though, of the evidence that could be adduced: if you study English poetry from the origin of the language in Anglo-Saxon times through year 1500 or so, you see plenty of organic growth. You even see swift development and change (after the eleventh century, when William the Conqueror grafted the language and culture of Normandy into the maturing tree that was England). But jump to the year 1600 and look at the poetry of Shakespeare, Spenser, Marlowe, Sidney—the difference between that and everything which came before is astonishing. Something new and unprecedented happened in the sixteenth century, and it’s clear that this something was interwoven with the culture of Greco-Roman Antiquity.

And that leads us to the next question: How can we define the Renaissance? What was its essence? Here are some answers that I have come across in my reading:

A cultural environment “in which scholars and poets were driven by a desire to bridge the gulf between present and past, or to speak to the classical dead.”

A “new way of looking at the world [that] sparked a passionate reawakening of interest in the classical civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome.”

“The revitalization of contemporary culture through the recuperation of antiquity.”

“A renewed grasp of the ancient world.”

Note the well-chosen words in that last one: “renewed grasp.” The Renaissance was not really a “rebirth” of classical culture, because classical culture didn’t die during the Middle Ages. The original “birth” was still very much in force. Instead, the Renaissance was a time when scholars and artists and statesmen renewed their relationship with the classical world, viewing it more as a world to be admired, emulated, and perhaps even idolized. A literary scholar named Thomas Greene described Renaissance art in terms that I find particularly apt: it shows us both “revived classical form” and “medieval form transmuted by a classicizing taste.” There’s your proof that the Renaissance can’t be all bad—when you look at the Renaissance, much of what you’re seeing is also medieval!

Seriously, though, scholarship nowadays challenges the idea of the Renaissance as a glorious and long-overdue escape from the barbarism of the “Dark Ages,” and we should be thankful for that. But still, something did change, and the change appears to have been a deep one—deep enough to send stress fractures all through the foundation of that magnificent house, called Christendom, that the Middle Ages built. “And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and smote upon that house, and it fell: and great was the fall thereof.”

If the Renaissance was animated by a “new” relationship with classical culture, what was the old—that is, the medieval—relationship?

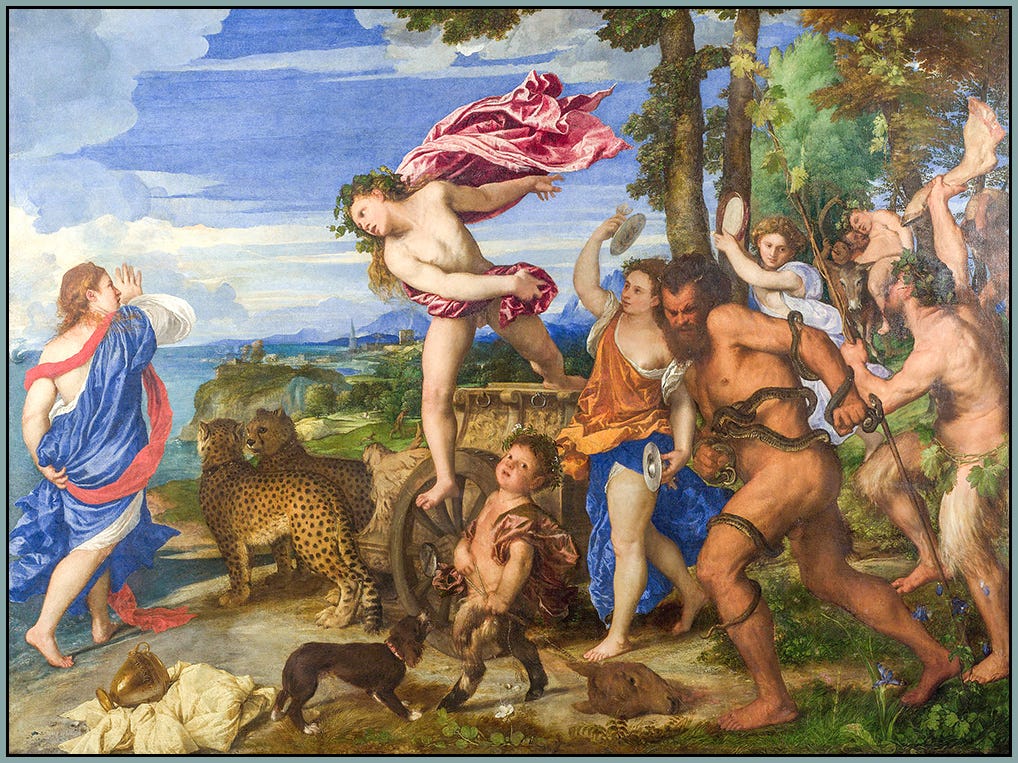

Renaissance humanists were more willing to accept and esteem Antiquity on its own pagan terms; this naturally led to a quest for imitation or restoration in which Christian spirituality was an obstacle, or an afterthought, or something to be shoehorned into la dolce vita of ancient Rome. I’m generalizing here—we certainly could find Renaissance notables who were more hesitant about flooding Christian societies with pagan culture. An interesting and somewhat perplexing example is Arthur Golding, a sixteenth-century scholar who translated Ovid’s Metamorphoses into English. This was a Herculean undertaking—the original Metamorphoses is almost 12,000 lines of poetic classical (read: difficult) Latin, and Golding translated them into rhyming couplets. And yet, Golding himself included a preface in which he denounced the errors of paganism and worried about readers who might be led astray! But overall, Renaissance thought was a major departure from the prevailing ethos of medieval societies. It’s hard to overlook the divergence when you see, for example, a painting like this:

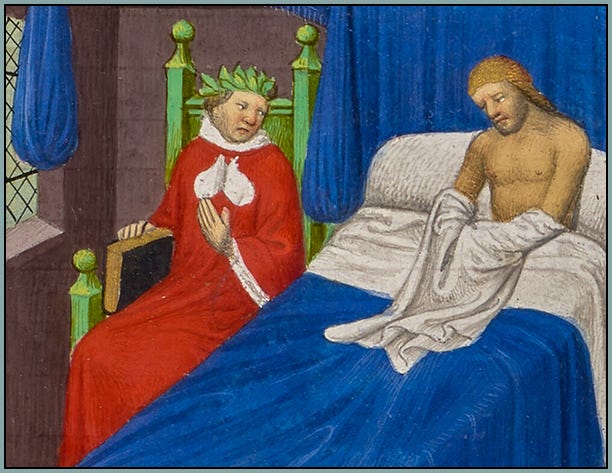

And then compare it to this:

In the Middle Ages, Christian spirituality was the gold standard. People recognized that classical authors and scholars and artisans were brilliant members of an illustrious civilization—but were also hobbled (or worse) by a deeply flawed religious system, and their works had to be proved and refined in the fire of the Gospel. Thus, classical culture was valorized in accordance with the medieval instinct for wholeness—of body and spirit, of self and community, and even of diverse historical epochs, which were all mystically united in the grand providential designs of God.

Antiquity preceded Christendom, and though the Greco-Roman world had much knowledge and beauty and heroism to offer, societies of the Middle Ages saw no sense in returning to a civilization that was, in the medieval model of history, a preparation for Christian civilization. They saw no sense in returning to a pagan world that was, by definition, imperfect, in the old sense of the word—unmatured, incomplete, unfulfilled.

We’ll continue this discussion on Tuesday by considering the medieval reception of two eminent masterpieces of classical literature, the Metamorphoses and the Aeneid. Before we conclude today, let’s treat the emergence of the Renaissance like a fable, and try to find the moral.

Looking at the Renaissance from a medieval vantage, while also incorporating our knowledge of how “early modern” societies eventually ended up somewhere in the “post-modern” abyss, we might describe the fundamental danger of the Renaissance as follows: overzealous humanists rediscovered the cultural glories of Greece and Rome, and in doing so they began to perceive Antiquity as a partial replacement for Christian civilization, instead of something to be thoughtfully and peacefully integrated into Christian civilization. They succumbed to that oldest of temptations—assuming that what you see and desire but do not have is superior to what you already have, even when what you already have comes directly from heaven.

What we must recognize is that this temptation inheres in human nature. The Christians of the Renaissance were perhaps the first to make this mistake on a civilizational scale. But they were not the last. Each successive wave of modernity—urbanism, commercialism, rationalism, empiricism, Romanticism, industrial capitalism, relativism, sentimentalism, to an extent even nihilism—has exerted far too much influence on Christian minds, lifestyles, and communities. Instead of judiciously allowing bits and pieces of goodness to filter in, Christians were all too willing to rewrite their religion according to the fads and fashions (and absurdities, and barbarities) of the modernizing West.

And right now, it’s not the classical past that is displacing, distorting, dissolving, consuming Christian culture. It’s the dehumanized present—the disenchanted, utilitarian, materialistic, technological world that surrounds us all but should not be allowed into our churches, schools, homes, and souls any more than is absolutely necessary. If we are ready to fault the Renaissance humanists for esteeming pagan, semi-secular Antiquity more than medieval Christendom, we must also ask what we have done, and are currently doing, to repaint traditional Christianity with the lurid colors of modern life.

The house of medieval civilization was built upon the rock of the Gospel, and it endured—grew, matured, flourished—for a thousand years. If Roman mythology or Greek philosophy could make that house a little more beautiful or majestic or sophisticated, all the better. But Christians of the Middle Ages had no interest in rebuilding their house according to pagan principles, and they certainly did not invite an un-Christian world to come in and chip away at the foundation. “And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house, and it fell not: for it was founded upon the rock.”

I fear that with the accelerating rate of church closures and the "commutization" of people into their silos (not that it's a bad thing necessarily), we are losing a sense of what is the neighborhood or town parish. We are constantly on the go, trying to find the perfect niche with like-minded people and to shut ourselves away from bringing other people in to see the true, the good, and the beautiful. "They're too far gone." I'm reminded of a quote from Sheen (or was it Chesterton?): There are a thousand people who hate the Church for what they think it teaches, but a few who hate it for what it does.

Tremendous piece of writing, astute and wise. I’d like to refocus slightly a few adjacent thoughts. I’ve been reading a short work that introduces Donald J. Keefe’s Covenantal and Eucharistic approach to theology, an inquiry that is historical and also metaphysical and ontological. Despite Balthasar’s concern that Keefe’s understanding of the Primordiality of Christ was a gnostic projection, I think, on the contrary, that it is a reflection built upon the concrete, historical meaning of Incarnation.

I bring Keefe up, because he understood, according to the small synopsis of his large theological effort, that the task of theology was rooted not in abstract hypotheses, but in ecclesial worship and liturgy that is historical in nature. Theology itself is ever an imperfect inquiry, so one cannot simply “canonize” past theological achievement, as if the future was only minor adjustments and whatnot, yet what mediates reality for theological insights is the objective reality of liturgical worship. And the latter, Keefe rightly recognizes, is the ecclesial fruit of the Eucharist. (Lose the foundation, and one becomes lost in a fragmented, debased imaginary.)

It seems to me that the “medieval” mode of synthesizing is actually the truly innovative creativity, because it arises from an eternal, transcendent gift. In contrast, the “nostalgia” for pagan liveliness was a retreat from the mystery of eternal life, and so a diminished nature ensconced in classical symbolism and putatively attainable by natural reason was exchanged for the unknown flourishing of Christian apocalypse which contains and transforms all the times.