Good Friday and Easter are two days of the year when I find it difficult to write prose. Ordinary language seems so inadequate for the greatest events—one ineffably tragic, one ineffably joyful—in the history of the world. On Easter especially I must say with Dante,

And there I saw a loveliness that when

it smiled at the angelic songs and games

made glad the eyes of all the other saints.

And even if my speech were rich as my

imagination is, I should not try

to tell the very least of her delights.1

So instead of prose I wrote a poem. (I included a full audio recording, in case that helps you get a feeling for the meter.) The language, alas, is modern English rather than medieval English, but nonetheless, the poem takes inspiration—in form and in content—from the poetic genius of the Middle Ages.

It is medieval in form because the stanza structure and rhyme scheme that I used, called Rhyme Royal, was introduced into English literature by medieval England’s foremost poet, Geoffrey Chaucer, who adapted it from French and Italian models. Over the centuries it was used by many others, including Gower, Shakespeare, Spenser, and (in slightly modified form) Milton and Wordsworth. Chaucer first composed in Rhyme Royal for a work which is among his most famous and is, perhaps, his best: Troilus and Criseyde, an epic poem set in ancient Troy and embellished with a love story of medieval origin.

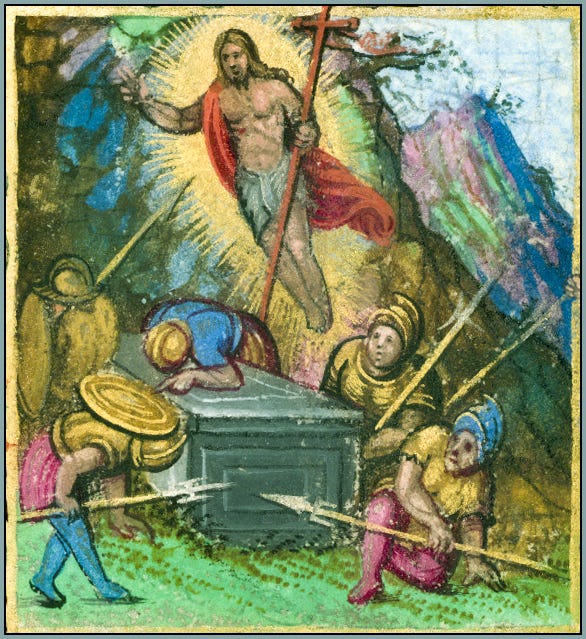

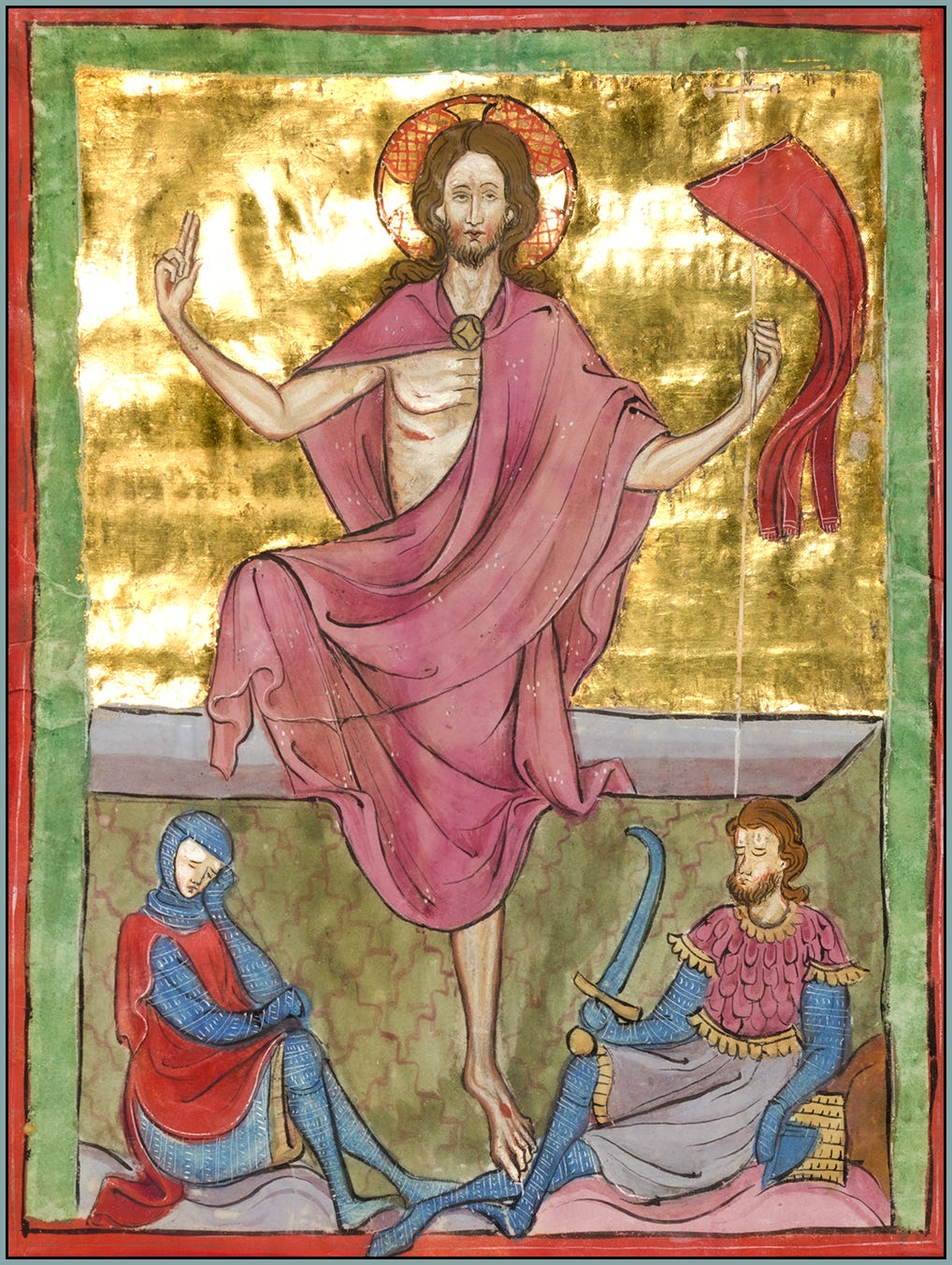

And that brings us to the content: weaving classical legends or myths into Christian themes is an eminently medieval thing to do, and that’s what I’ve done in the poem below, which I’ve entitled, following Chaucer, Numa and Egeria. We’ll talk more about Rhyme Royal, and about the Resurrection of the King of kings, on Tuesday.

Numa and Egeria is based on the myth of Hippolytus, and my principal source was the version of the story given in Book 15 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. It is—in the medieval understanding of history—an Easter myth, and I hope that my retelling deepens its resonance with the august and timeless mysteries of our Redemption.

Her heart was broken when he died, that priest

and noble king called Numa, he who taught

the Romans sacred rites and how to feast

and pray and live in peace, who ere then fought

and only war could make, and ever sought

to dominate by sword their fellow man

and spill the blood whose course with Cain began. A mountain nymph, Egeria her name,

a wife unto that second king of Rome,

in beauty and in wisdom was her fame

and Numa saw this, brought her to his home.

She savored life as honey in the comb

until of man’s mortality the taste

her tongue embittered and her joy effaced. This nymph, alas, was not well versed in death, a goddess, she, whose life lives ever new, whose lovely form has always light and breath, whose spirit does what man’s can never do: be with the body one, and never two. The day must come when Numa’s soul will flee, which for the nymph an agony will be.

Numa, Latin king, waxed strong and reigned,

he clothed himself in noble deeds and fair

but as the ageless gods looked on, he waned

and died as all men do, and everywhere

was weeping: lamentation stained the air

of Rome. And there amidst ten thousand cries

was heard, her voice, and seen, her bloodred eyes. “Grant me to die! Let my unbeating heart

be cursed—be sheath to every Roman knife,

be resting place to every Roman dart,

until is slain my everlasting life

and I in Hades am again his wife!”

Thus she grieved and raved until she fled

into the woods: her love and king was dead.Pierced by fitful moaning was the silence

of the woodland realm, where nymphs had found

Egeria; they wondered at the violence

of the dark despair that held her bound:

her tears, divine, were dew upon the ground.

A man drew near; he stopped; he saw her face.

Though not a god, he spoke with skill and grace.“Perhaps you think you are alone in pain

that seems to plague the soul and poison thought,

but others suffer much. Your tears are vain

when made a poor recluse. Your tears are nought

as mirrors to your woe. You truly ought

to look at others’ sorrows as your own.

Now I will tell the sorrows I have known.”To that sad nymph he sang of Hippolytus,

a handsome youth of perfect chastity,

he was the son of noble Theseus,

who ruled Athens, brought her unity,

but to his son brought fell calamity:

Hippolytus was charged with grievous sin

and Theseus, believing, banished him.His accuser on foul lust had fed:

the mother of Hippolytus had died

and Theseus another woman wed,

to Phaedra now a fatal knot was tied,

who sacred bond of marriage had defied.

Her husband was, in her eyes, now outdone,

and slighting father, she seduced the son. An island princess that poor temptress was,

dark hair and eyes, fair skin, and coral lips,

she thought the battle quickly won, because

her charms were like a fearsome fleet of ships

and youthful men do little to resist.

Hippolytus, so much unlike the rest,

was nonetheless put sorely to the test.Perchance he had succumbed if he were not

devoted to that deathless virgin queen:

Artemis, the goddess of the hunt,

whose shield to guard the chaste is often seen,

and like the moon is mighty and serene.

“Begone! For I would never thus betray

my father and my goddess, come what may.”And yet, what came was than he thought far worse:

Phaedra painted him with her black vice,

telling Theseus he was perverse—

that his own father’s consort did entice!—

and then with rope she ended her own life.

Why the king believed her we know not,

but in her net Hippolytus was caught. In wrath the father banished his own son,

whose fate was far more dire yet than this,

for Theseus invoked against him one

of those three curses that were justly his,

Poseidon’s gift, now tragically amiss:

the sea god heard his prayer and sent a beast,

and thus by one vile sin are more unleashed.Stricken, lashed, by wrongful accusation,

injured, outraged, by his closest kin,

cast out, beyond the walls of his own nation,

punished, chastised, for another’s sin!

And now his final torment must begin.

He in his chariot was forced to flee,

and now in Corinth rides hard by the sea. There beneath the water danger lies,

the horses sense that fey, immortal wrath,

they see a mountain from the waves arise,

a horned and monstrous bull that blocks the path,

Poseidon’s fiend—the horses start to thrash

and wild now with frenzied terror rove

then charge like hell-bred hounds into a grove. Useless are the reins within his hands,

worthless is his strength to change their course,

hopeless are his vehement commands,

a suicidal race for man and horse

comes quickly to an end with fatal force:

the tree that broke the chariot is red

with blood that good Hippolytus has shed. Like a ship washed up along the shore,

beaten, battered, pounded by a gale,

deck all strewn and marred with wooden gore,

wretched shredded rags the gleaming sail,

timbers blasted, hull about to fail—

such a sight was that young man to see,

whose forlorn mangled corpse hung from a tree.Egeria looked up. The tale was done.

Her tears indeed had long since ceased to flow.

Entranced she was to learn about the son

of Theseus, and more she wished to know

about this youth who languished deep below

the very earth on which her body lay.

The speaker turned; she asked him please to stay.“And is there truly nothing more to say?

Hippolytus is dead, King Numa, dead?

How would your words console me, I who pray

to die—a torture thus to live unwed,

an anguish without him who shared my bed!”

The speaker lifts his eyes, and through the leaves

the sun arises while the goddess grieves.“Egeria,” the noble man—still young—

calls out; a blackbird sings, awakes the dawn

while thrushes chime angelic notes among

the blooming briars where a lonely fawn

was lately caught, its blood was left upon

a thorn whose hope in suffering appears:

the goddess slowly bathed it in her tears. “Egeria!” The word was not the same, now stronger, fuller, godlike, and mysterious, “you heard my song but never asked my name. I am, who speak to you, Hippolytus, but since my death am called, and truly, Virbius: for as a man, a vir, as Latins say, I am born bis—two times—to life’s first day.”

“Look, behold my light, my radiant face,

no blood, no tears, no stain of Phaedra’s sin—

Asclepius gave me restoring grace—

my limbs, my chest, my voice, my eyes, my skin,

all sound and strong and beautiful again!

Weep not for Numa, you are yet his wife:

through Me, he has, like you, eternal life.”Paradiso, canto 31; Mandelbaum translation.

In nomine Domini resuscitati, salutem et benedictionem.

Magnificent! Thank you! A Blessed Easter to you and yours!