“A Forest of Symbols”: Sacred Liturgy in the Middle Ages

Reflections on a chapter from Peter Kwasniewski’s latest book

Many of you, I imagine, are aware that there’s some disagreement in the Catholic world about how church services should be conducted. Many of you are aware also that the phrase “some disagreement” is a massive understatement—the debate, whose roots go much deeper than the Second Vatican Council, has shaken the foundations of the Church and entered into the lives of communities all over the world. It must strike certain observers as odd that liturgical rites should provoke such enduring, widespread, impassioned, even acrimonious controversy, but from a historical perspective it is not, for human societies tend to be quite serious about how their God or gods will be invoked and worshipped. Consider, for example, the ancient Greeks, who for secularized modern folks might conjure up thoughts of pleasantly risqué mythology, intellectual sophistication, and a relaxed Mediterranean lifestyle unencumbered by Christian “dogmatism”:

Along the shore, the men of Pylos stood,

offering sacrifices—jet black bulls—

to please the dark-haired god who shakes the land:

Poseidon, lord of quakes and shifting sands.

Nine sectors had been traced along the beach;

five hundred men had been assigned to each,

and every sector sacrificed nine bulls.

Now, after tasting of the inner parts,

the men of Pylos, with their feast in course,

were offering burnt thighbones to the god.1

This is from the Odyssey; note the attention to ritualistic detail and the mathematical precision in the ceremony’s use of sacred number.

This next example is from an especially vivid passage:

Old Nestor, master charioteer, brought gold.

The smith so thinned it down that it might coat

the heifer’s horns—and fill with deep delight

Athena when she saw the sacrifice.

…

And, from within the house, Arétus brought

a basin that was bossed with floral forms—

a basin filled with lustral water—while

the basket in his other hand held barley.

…

Then Nestor, master charioteer, began

the rite: he washed his hands and sprinkled barley,

prayed to Athena fervently and cast

hairs from the heifer’s head into the flames.

The description of the sacrifice continues, in this translation, for another twenty-four lines.

My point here, again, is that human cultures used to take religious ceremonies, including the details thereof, quite seriously. This is a natural and, furthermore, perfectly sensible thing to do when one actually believes, as did Odysseus and his countrymen, that heavenly beings exist and have power over earthly life. Indeed, I see no room for modernity’s ritualistic indifference or casual iconoclasm in the liturgies of the Odyssey. Rather, I imagine that if a bystander walked up and told Nestor that the gold was a waste of money, then chuckled at his pointlessly sprinkled barley, then poured out the lustral water to prove that it was unnecessary, he would have been killed on the spot.

Though interwoven in some way with almost everything that I write for Via Mediaevalis, the question of liturgical praxis doesn’t receive much direct discussion in this newsletter. This occurs in part because other writers are already fully committed to it, and here we have many other topics that need to be explored.

It occurs also, however, because the issue of modernized vs. traditional liturgy was virtually nonexistent in the Middle Ages. To the extent that this newsletter gives us an opportunity to experience, intellectually and poetically, the culture of medieval Christendom, the sense of liturgical conflict must diminish, because the sacred liturgy grew slowly and organically during the Middle Ages and was far less susceptible to centralized decision-making. Abrupt, extensive revisions like those published by churchmen in the twentieth century were, in the twelfth century, simply inconceivable. I say again: not within the realm of that which could be imagined. Making drastic modifications to consecrated, inherited rites regarded as supremely important for the well-being of society and the salvation of souls—such would utterly contravene the medieval ethos, which insisted that innovation be distrusted, tradition be respected, and the noble past be preserved. It would be opportune to repeat a quotation, from the most illustrious philosopher of the Middle Ages, that I included in Tuesday’s post:

The customs of God’s people and the institutions of our ancestors are to be considered as laws. And those who throw contempt on the customs of the Church ought to be punished as those who disobey the law of God.

—Thomas Aquinas, S.T. I-II, Q. 97, art. 3

I try to ensure that this newsletter is not about me and not even about “my” perspective on culture, creed, society, and spirituality. Who am I? Nobody—one fleeting ripple in the vast ocean of history, one lamed foot soldier in the good God’s innumerable host. My thoughts are worth your while insofar as they derive from, resonate with, and cast light upon the greatest and truest thoughts of Greco-Roman-Judeo-Christian civilization, which has been accumulating beauty and wisdom and exemplars of virtue for a few thousand years now.

I hope it is also apparent that I’m open-minded and not of an argumentative disposition. If you and I disagree about the liturgical practices that are most compatible with human happiness, most conducive to Christian sanctification, and most pleasing to Almighty God, I’m okay with that. I don’t expect to convince you (though if you want to be convinced I am more than willing to help :), and you’re not likely (that’s another understatement) to convince me. Indeed, my case is an especially hopeless one for those who favor the Church’s modern liturgy, as I pointed out some time ago when responding to a thoughtful reader who does indeed disagree with me, and who kindly broached the issue. I explained that

I do for various reasons consider the Old Rite superior to the New Rite, and with regard to its poetical excellence in communicating spiritual realities, I consider it greatly superior. And honestly, this is the only coherent position for someone like me who is so passionately dedicated to the wisdom and spirituality of the Middle Ages: though the Old Rite has roots in the early Church and even in the Old Covenant, its liturgical forms as we now know them are the fruit primarily of medieval culture. Indeed, the traditional Roman liturgy is the central and ultimate masterpiece of medieval culture.

That being said, one should not be surprised to learn that I thoroughly enjoyed and highly recommend a new book from my friend and colleague

: Close the Workshop: Why the Old Mass Isn’t Broken and the New Mass Can’t Be Fixed. It is an absolute tour de force. As I wrote in an extensive review to be published elsewhere, Kwasniewski has produceda remarkably thorough and wide-ranging text; if there’s a liturgical topic you’ve pondered at some point during the last sixty years, chances are it’s somewhere in this book—and even if you’ve read about it a dozen times already, you’ll probably find something new in Kwasniewski’s characteristic blend of extensive research, rare erudition, and stylistic pungency.

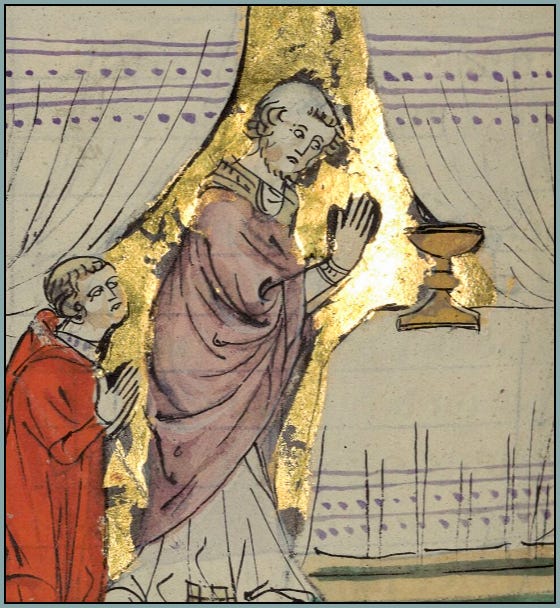

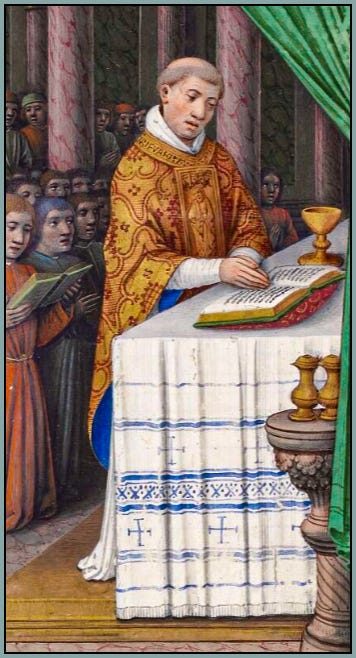

Our objective today is to gain insights into the way Christians experienced the sacred liturgy in the Middle Ages, and we’ll do that using just one chapter from Close the Workshop: Chapter 15, “Allegory as a Key to Understanding Traditional Liturgy.”

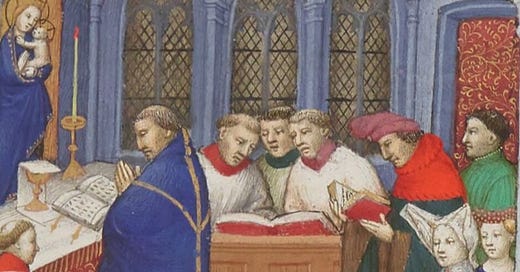

The term “allegory,” as I explained in a previous post about medieval paradox, “derives from Greek allo- and -agoria and therefore suggests ‘speaking the other,’ that is, sharing deeper wisdom and higher truths by telling two stories at once.” Medieval Christians were highly attuned to allegorical modes of thought, and some perceived the Mass as a symbolic narrative involving not only the immediate realities of liturgical ritual but also mystical realities such as events in the life of Christ.

The distinguished literary scholar O. B. Hardison (d. 1990) found that “full-scale allegorical interpretation” of the Mass began, and not without controversy, as early as the ninth century, with the writings of Amalarius, Bishop of Metz. His work responded to the laity’s desire for “a vivid, dramatic understanding of the Roman rite” and was, therefore, quite popular. As evidence of how diligently the medieval Church safeguarded her liturgical treasures, some members of the hierarchy condemned Amalarius for his “fanciful” theories, though the man was hardly a subversive innovator by modern standards. He was, rather, a learned and devoted student of the liturgy who contributed to the development of the Roman rite at a time when it was absorbing elements from the Latin rites used in Gaul. Though Amalarius went a bit too far with his liturgical mysticism, uniting one’s mind and heart to the Mass through temperate allegory is a sound practice validated by “a long succession of interpreters”—including Hugh of St. Victor, Pope Innocent III, and Thomas Aquinas—who “carried on and elaborated the tradition initiated by Amalarius.”

Kwasniewski insightfully connects liturgical allegoresis with the need, especially acute in the modern Catholic milieu, of cultivating a humble and receptive encounter with sacred liturgy:

The contemplative atmosphere of the classical Roman liturgy has nurtured in me a patient, open-minded, speculative disposition towards texts, music, and ceremonies. My habit of mind is now to ask, in accord with the allegorical method of our ancestors: “What meanings can I glean from the liturgy as it exists in front of me?” rather than “How could it be improved according to my own ideas?”2

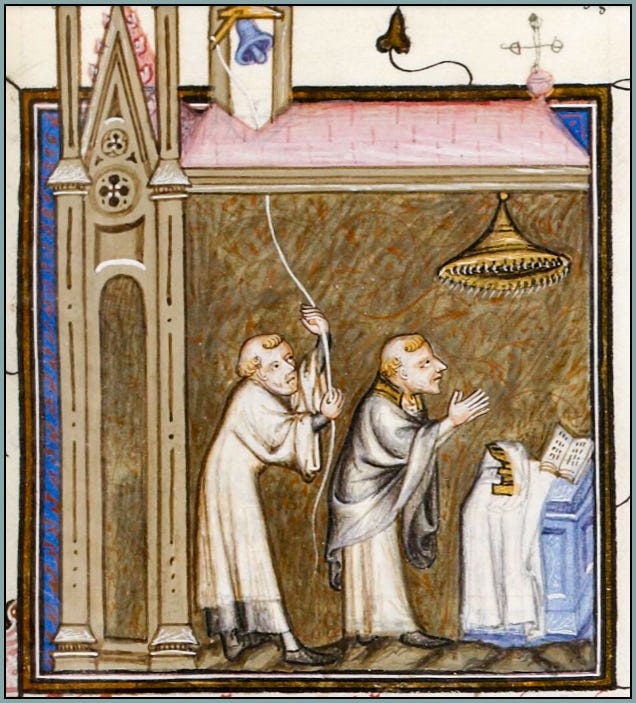

He discusses the custom whereby sacred ministers sit down during the Gloria and Credo. Through liturgical allegory, this seemingly pragmatic custom acquires mystical significance: “I can honestly say that I had never pondered the mystery of the ‘session’ or seatedness of the Son of God until I had seen ministers at the High Mass and Solemn Mass moving from the altar in a liturgically dignified manner and sitting down ceremonially.”3 This example, from just one minor feature of the Mass, gives us an idea of the extensive poetical richness that medieval Christians could discover in the liturgies they attended. This richness should be available to modern Christians as well, but unfortunately, “allegorical interpretation of the liturgy … was totally rejected during the period of liturgical reform, and even earlier by liturgists who tended towards rationalistic or reductionistic explanations.”4

One of my favorite verses from the Bible is Matthew 13:52: “every scribe which is taught unto the kingdom of heaven, is like unto an householder, which bringeth forth out of his treasure things both new and old.” This fecund balancing of new and old is essential to my understanding of sacred tradition, and Kwasniewski shows how allegorical interpretation of the liturgy helps us to fruitfully understand and apply this principle. The objective is not to remove some (or much) of the old treasure so that it can be replaced by something new, but rather to preserve the old treasure while making our experience of it new: the ceremonial actions of the Mass can always acquire

new meanings, new interpretations, new resonances. In its fine texture of details, the traditional liturgy speaks both the same messages and new messages to each generation. Like an ancient epic poem, the same text reads differently in this or that age, without losing its remarkable ability to transcend them all.5

As [Fr. Claude] Barthe points out…, for over a thousand years the Roman Mass was approached as a “forest of symbols.” Every part of the rite, every ceremony, down to the smallest sign of the cross or movement from left to right or incensation pattern, was eagerly mined for meaning.

—Close the Workshop, p. 263

An ancient and medieval liturgy reaches its full potential when received and appreciated according to ancient and medieval modes of thought. Kwasniewski’s discussion invites us to reflect on the calamitous dissatisfaction with which many twentieth-century Catholics regarded a Mass that was cherished for centuries by countless peasants, priests, scholars, and saints. Without oversimplifying a complex situation, we must recognize that a prodigiously symbolic liturgy will lose some of its appeal when those celebrating it and attending it dismiss, or even disdain, the medieval art of living a symbolic life. If, in an even worse scenario, that which replaces this allegorical spirituality is “the sterility of academic rationalism,”6 the liturgical rites of our ancestors are bound to seem inefficient, inaccessible, incomprehensible. It is rather unfair, though, to blame the liturgy for this, since people, not the rites, were the ones that changed.

And that leads us to one of the most memorable and important sentences in Close the Workshop:

Fundamentally, we ourselves are the ones who need reform, not the liturgy.

All three excerpts are from The Odyssey of Homer: A New Verse Translation, by Allen Mandelbaum.

Close the Workshop, p. 253.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 256.

Ibid., pp. 256–57.

Ibid., p. 264. The concluding quotation is from p. 212.

Thank you for a thoroughly thought-provoking read! That last quotation is so well chosen: "Fundamentally, we ourselves are the ones who need reform, not the liturgy."

If the traditional Roman liturgy "does not speak to modern man," as the critics of the traditional Mass and Divine Office claim, then it is not because there is something wrong with the liturgy; it is because there is something seriously wrong with modern man.

"Making drastic modifications to consecrated, inherited rites regarded as supremely important for the well-being of society and the salvation of souls—such would utterly contravene the medieval ethos, which insisted that innovation be distrusted, tradition be respected, and the noble past be preserved"

Definitely true regarding the later medieval era of which you seem to speak. Curious if Dr. K's book discusses the earlier "drastic" reforms that developed those inherited rights - e.g. the Visigothic introduction of propers that specifically combat the heresy of Arianism and promote Marian theology?