A Fundamental (Modern) Problem of Christianity

or, A Tale of Two Christmases

Year after year after year of reading books and articles and news reports on so many different aspects of the Christian religion, and yet I’ve never seen the problem articulated in quite the way I have in mind. Maybe that’s a sign that I’m just wrong. Or maybe this is common knowledge that I’ve somehow never come across, and that is too obvious to merit discussion.

I’m going to discuss it anyway.

The Christian religion, despite vicious persecutions and a variety of logistical impediments, took the ancient world by storm. The culmination of this momentous, civilizational rebirth was the youthful period that we call the Middle Ages—one thousand years during which virtually everyone in western Europe believed in and practiced Christianity. To “believe in and practice Christianity” is not to be a saint. There was no shortage of sinners and scoundrels in medieval society. But the sinners, at least in their better moments, were mindful of the God who abhorred their iniquity and hoped for their conversion. And the scoundrels, probably even in their worst moments, wanted to have faith and to be a part of the vast Christian family that surrounded them. Those who didn’t were few in number and belonged to one of two general categories: Muslims and Jews who had no interest in renouncing their ancestral religion, and residual pagans, whose descendants would eventually embrace the Gospel and entrust their lives to a world so overflowing with Christ that it was not a kingdom but rather a Christendom.

The sixteenth century was the long and complex transition from medieval to modern society. The early modern period, however, was still intensely religious. Despite the gradual ascent of secular values—commercialism, humanism, nationalism—it was still shocking and scandalous when, for example, a public figure like Christopher Marlowe dabbled (allegedly) in atheism. The Scientific Revolution came along and made Christianity look rather unscientific, but belief remained crucial to personal and social life. The Enlightenment brought skepticism to new levels and painted historical Christianity as hopelessly unenlightened, and yet, the Christian experience mysteriously endured—even Voltaire, that monumental crusader against the “infamy” of non-Voltairean Christianity, “built a Catholic chapel on his property and attended Mass. He sent his workers to Mass and had their children taught the Catholic catechism. He accompanied his solitary meals with sermon readings. He was an active member of a Catholic lay order. He put in writing that he wanted a Catholic burial.”1

But then, after a revival of sorts in the nineteenth century, a process of unprecedented—I say again, unprecedented—dissolution began. Soon there were immense segments of the Western population who regarded anything resembling historical Christianity as simply impossible. The cultural descendants of Christendom somehow developed an overpowering blind spot where the Christian religion once was: they could not believe it, could not practice it, could scarcely even fathom its existence.

We are in the late stages of this process, the results of which I need not describe. You see them all around you.

The religious and spiritual state of postmodern society is a complex reality that has emerged from an equally complex interplay of historical forces. I have no intention of denying or downplaying any of that complexity.

At the same time, though, the fundamental message of Christianity is simple, and perhaps it’s worth our while to think in simple ways about the fundamental problems of Christianity in modern culture. My proposal—which is built from many years of formal education and personal experience, and which, as I mentioned above, seems to be largely absent from discussions of this nature—is as follows:

Christianity is, quite simply, too good to be true.

Now let me make that more specific:

For a world without joy—a world that has largely forgotten how to be deeply, vibrantly, communally joyful—Christianity is too good to be true.

A providential, fatherly Creator who made us out of nothing and breathed His life into us and loves us with an infinite love? A God who became a Man so that He could teach us and heal us and enamor us and die for us? Forgiveness of sins, even the worst sins, even seventy times seven of the worst sins? The deep, psychologically transformative pleasure of knowing with certainty that some things are true and some things are false? A bare minimum of non-negotiable religious duties, all of which are perfectly consonant with basic human happiness, and one of which involves a single day of the week when we are “obligated” to practice leisure and attend a liturgical service that is—that should be—a delightful experience appealing powerfully to the intellect, the memory, the poetic sense, and all five physical senses?

Divine compassion for illness, pain, poverty, sorrow? The sublimation of suffering, which imparts transcendent value to afflictions that we all must endure anyway? The destruction of death, which need no longer be feared? The possibility of reuniting with deceased friends and family?

The hope of perfect, unalterable, everlasting joy and celebration in a celestial paradise?

How many people nowadays look out from their world—at its worst, a nihilistic, agnostic, consumeristic, relativistic, dehumanized, roboticized, skeptical, pragmatical, isolated, fragmented, increasingly substance-enhanced and tragically despair-ridden world—and simply say “No.” Christianity is implausible, improbable, inconceivable. It’s a fairly tale, a myth, a dream. Nothing that hopeful could be real. Nothing that good could be true.

Sometime in the fourteenth century, a curious event occurred in the history of the English language. The Old English word wuldor, which was the standard equivalent to Latin gloria (or Greek doxa) had gradually faded away, and English writers of the late Middle Ages found themselves without a word for “glory.” What to do?

Modern Englishmen would have filled the gap by importing a word from the Continent. But medieval Englishmen came up with a different solution: they took a related word and enriched its meaning. Which word did they choose? “Joy.”

We see examples of this in a fourteenth-century translation of the Latin Psalter into Middle English:

minuisti eum paulominus ab angelis: gloria et honore coronasti eum

thou lessid hym a litel fra aungels: with ioy and honour thou coround himcaeli enarrant gloriam dei

heuens tillis the ioy of Godet gloriabuntur in te omnes qui diligunt nomen tuum

and ioy sall all in thee that lufis thi name

We see it in the mystical text Scale of Perfection, by the Augustinian Canon Walter Hilton (d. 1396), when he comments on a Latin text and expresses the idea of the gloria of the Lord:

We … bihalden, as in a miror, heuenly ioye ful schapin and onyd [united] to þe ymage of Oure Lord.

We find it even in a translation of a very familiar prayer:

Gloria Patri et Filio et Spiritui Sancto, þat is, Ioye to þe Fadir, Sone, and Holy Goost.

This word was not chosen by accident. It was chosen because joy is not just an idea, and is much more than a feeling, and is not incompatible with the travails and misfortunes of our earthly pilgrimage. Joy is a social experience, an act of the will, a religious practice, a heavenly reality. It is, or at least it used to be, a way of life.

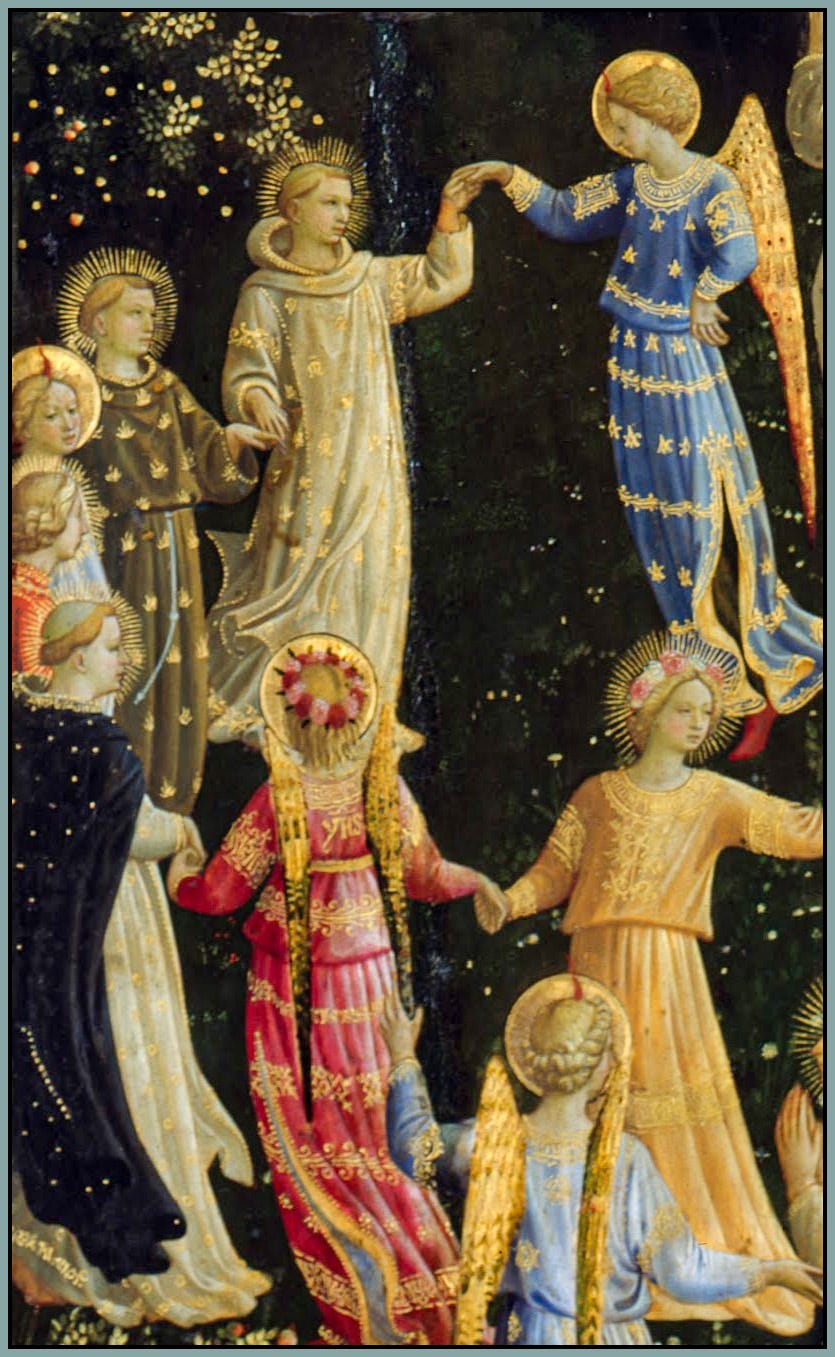

In the High and Late Middle Ages, the practice of Christianity was universal; the birth of the Incarnate God was a historical fact that informed and spiritualized the entirety of human civilization; Christmas began on Christmas; and the season of Christmas continued into January, with joy-filled revelry and feasting on a scale that is, for us, unimaginable.

In my corner of the modern world, the practice of Christianity is a withered, distorted shadow of its former self; the commercial Christmas emerges sometime in October; the season of Christmas, which in spiritual terms never really began, ends on December 26th; and the post-Christmas period is notorious for widespread loneliness, disappointment, and depression.

Authentic Christianity brings joy. But let’s not forget the converse of that statement: authentic joy brings Christianity. We need more of both.

How to recover them? Well, that’s the hard part. Returning to a more medieval Christmas would be an excellent way to start. And when it comes to stirring up some deeply human joy in a weary human heart, dancing works wonders—so I guess I’ll conclude with some advice borrowed from Shakespeare, Love’s Labor’s Lost, Act 5, scene 2:

The music plays. Vouchsafe some motion to it.

H. W. Crocker, Triumph: The Power and the Glory of the Catholic Church. Three Rivers Press (2001), p. 334.

The sin of despair indeed. Where there is no hope, there is no joy. Thank you, Robert, for having the courage to speak - it definitely did need to be said, and I for one, really needed to read it. A merry, joy-filled Christmas to you and your kin!

Joy to the world!