Language is the house of being. In its home, man dwells.

—Martin Heidegger

Those who study and write about medieval culture, myself included, say things that imply a knowledge of thought processes, mental habits, and modes of perception—despite the fact that there are no medieval people around to tell us how they think, how they structure their mental space, and how they perceive the exterior world. Why can anyone claim to have such knowledge? How is it possible to integrate “the medieval mind” into discussions presented as primarily factual rather than conjectural or imaginative?

Part of the answer comes from something that often finds its way into the pages of Via Mediaevalis: literature. A maxim that I like to keep always at the ready, just in case someone stops me on the street and asks why we should bother studying literary “fiction” instead of historical “fact,” is that “history tells me what people did, but literature tells me what they thought.” This is an oversimplification, but it gets the point across: literature is a window into the interior world—sensations, relations, understandings, ideas, beliefs, values, desires, dreams—of individuals and communities that lived in the Age of Faith (rather than the age of humanism, or “enlightenment,” or industrial capitalism). I delight in history and esteem it highly, but it is literature that tells me more eloquently and shows me more vividly how to rediscover reality, reimagine human life, and reform my own self.

Even literature, however, provides a somewhat indirect path into the medieval mind. People didn’t sit down and write books with the express intention of revealing the shape and structure of their thought, as though sketching the framework of a Gothic cathedral. Books, then as now, are written to give pleasure (of story, rhythm, rhyme…), to convey moral or spiritual truths (through imagery, allegory, character…), and to stir the emotions (which naturally and powerfully respond to tragedy, comedy, and rhetoric). Thus, narrative, poetry, and symbolism reflect the medieval mind like a windswept lake reflects a mountain: a likeness is there, but so are the waves of drama, passion, and art. We ought also to look when the waters are still: that is, when the reflection appears in something more unified, more fundamental, more primal—something that is not quite literature, but of which literature is made. Here I refer to language itself.

Christ alwayes in hys speakynge dyd vse fygures, metaphores and tropes.

—Bishop Edmund Bonner (d. 1569)

Most of us, I think, learned about metaphors in school. Maybe you still have the definition in your head: “a comparison without using ‘like’ or ‘as.’” In my opinion this isn’t even quite right, since a comparison that does use “like” or “as” is still a metaphor; it’s just a special type of metaphor now called a simile. But beyond that, the definition makes metaphor sound about as interesting and important as a doorknob—at best maybe a handcrafted, wrought-iron doorknob that catches the eye more readily, and sustains conversation a little longer, than something that came out of a factory.

This is a sad state of affairs, because it is likely that without metaphor, human civilization as we understand it would not and could not exist. The reason, if you boil it down, is fairly simple: culture, especially Christian culture, cannot flourish in the absence of metaphysical realities, and human beings cannot adequately comprehend and communicate metaphysical realities without metaphorical thought and language.

Let’s elaborate upon that. A metaphor is not fundamentally a “literary device.” It is a way of expressing something so abstract or profound that human beings cannot adequately express it in direct, “factual” language. Metaphor allows us to use strong, clear, deep-rooted sensory knowledge to understand and explain things that surpass our physical senses and perhaps our intellectual faculties as well. Furthermore, it allows us to experience these things in ways that captivate and resonate and transform. “The Lord is my shepherd,” says the Psalmist, “in a green pasture he giveth me rest, by peaceful waters he leadeth me.” How many lives have these Hebrew words—recited for thousands of years, translated into who knows how many languages from all over the world—how many lives have they enriched by imparting a new understanding of, appreciation for, and relationship with God and His presence in human life? And yet, none of this is “real.” God is not (literally) a shepherd, and the believer is usually not resting in a green pasture or walking by peaceful waters. It’s all metaphor: a pleasing, consoling, inspiring feast of sensory knowledge is used to express the inexpressible perfection of divine Providence.

For a long time now, metaphor has had a special relationship with poetry. This is, by the way, a quick and effective, though incomplete, answer to the question of why all children should extensively read, and all schools should diligently teach, poetry and poetic literature: it helps us to think metaphorically, and without the capacity for metaphorical thought, a person’s encounter with culture and religion will be weakened, eroded, even undermined. And without culture and religion, man is too little like man, and too much like the beasts.

However, scholars have recently been more attentive to the role of metaphor in everyday language, and rightly so: this does not devalue poetry but rather confirms that metaphor is a vital organ in mankind’s intellectual and spiritual life. It also supplies motivation for an impressive scholarly project that I want to introduce in this post, because of its special ability to provide insight into the medieval mind. This project is called the Metaphor Map of Old English.

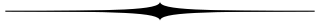

Language is thoroughly intertwined with thought, and metaphor reveals something about how language and thought reach up into the cosmos, out into society, or down into the soul. A metaphor map displays details of a particular mental world using the intersection of metaphor and language, and when the language in question is Old English, which was spoken during the Middle Ages and died out long before the modern period, that mental world is a medieval world.

The Metaphor Map of Old English is available online, for free. The main page shows the diagram below, which the site describes as a representation of “all recorded knowledge in Old English: every word in every sense which we have evidence of from the Anglo-Saxon period.” The white lines are “metaphorical links in language and thought between different areas of meaning.”

As you might imagine, a lot of work went into this, and the methodology is not something I will attempt to explain in detail. The bottom line is this: the researchers used a comprehensive historical thesaurus to find words that have meanings associated with different categories of human experience, and then these words were analyzed manually to identify meanings that “overlapped” metaphorically.

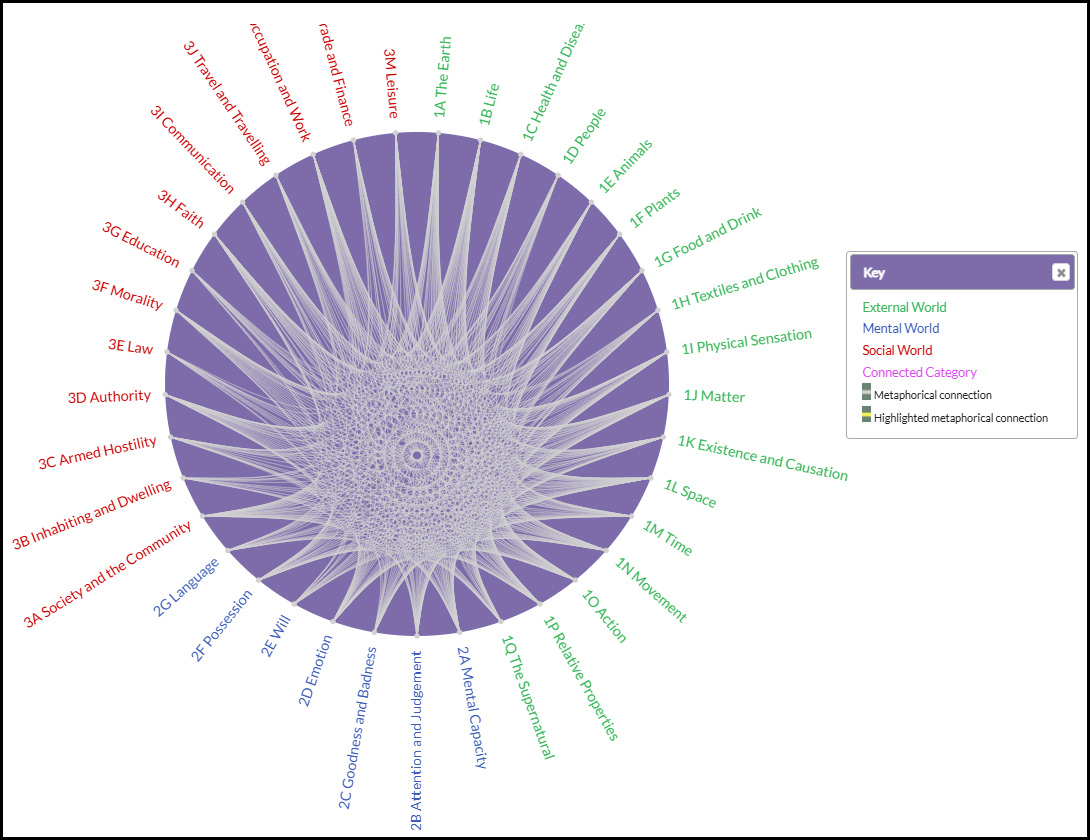

For example, “storm” (which is an Old English word) appears in both the “atmosphere and weather” category (with its literal meaning) and the “vigorous action” category, where it means “violent or tumultuous action.” Thus, we have a metaphorical link: early-medieval Englishmen used the sensory, elemental realities of a storm to understand and express the behavior, perhaps also the mental state, of human beings engaged in a rebellion, a riot, a brawl, etc. This is one way in which the site can display the link:

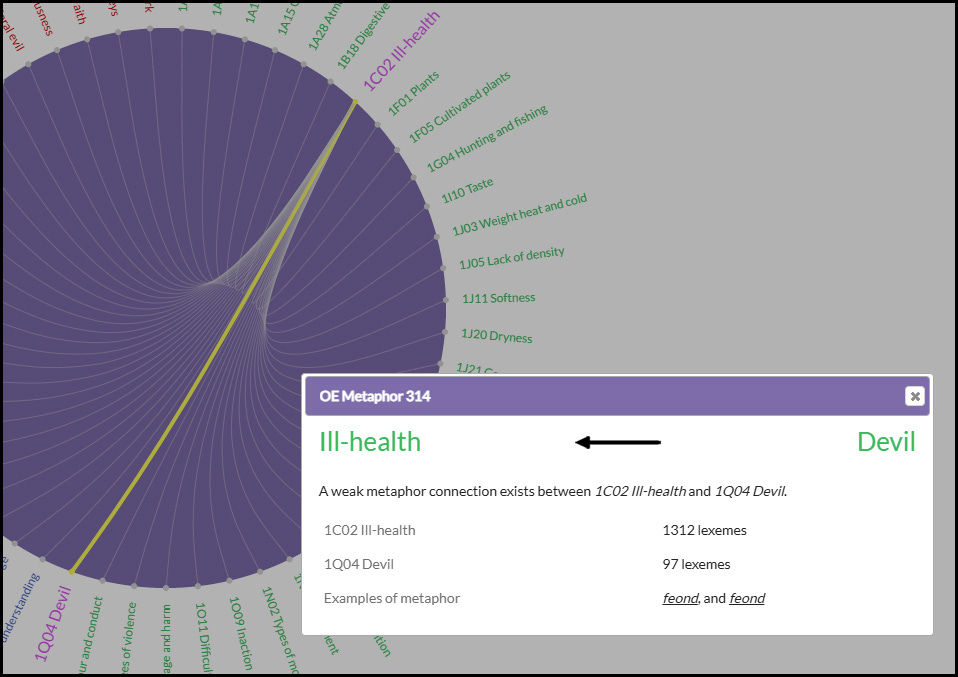

Another example is the word feond, meaning “devil.” (The same word, spelled “fiend,” still exists in modern English, but we don’t normally use it to denote the devil.) Old English feond appears also in the “ill-health” category:

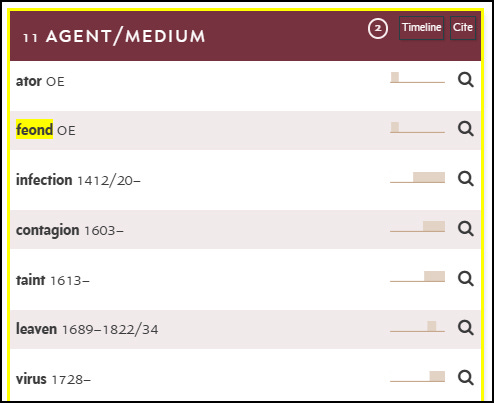

One click takes you from the metaphor map to the Historical Thesaurus of English, where we find that feond is listed among words for the agent or medium of disease. This metaphorical connection suggests that in the medieval mind, the devil fulfilled a role similar to that of “contagion” or “virus” in the modern mind:

Modern medicine would chuckle at this as an example of medieval ignorance and superstition—“those poor rustics, they knew little about human biology and nothing about microbiology, so when someone got sick all they could do was blame the devil.” My interpretation is rather different: The medieval mind was a place of wholeness rather than scientific materialism. Perhaps medieval Christians knew nothing about microbiology, but they knew a great deal about the spiritual life and about the union of body and soul. To say that a man is sick because he “has a feond” is to see more deeply into disease, and to recognize that the natural result of an unhealthy soul is an unhealthy body.

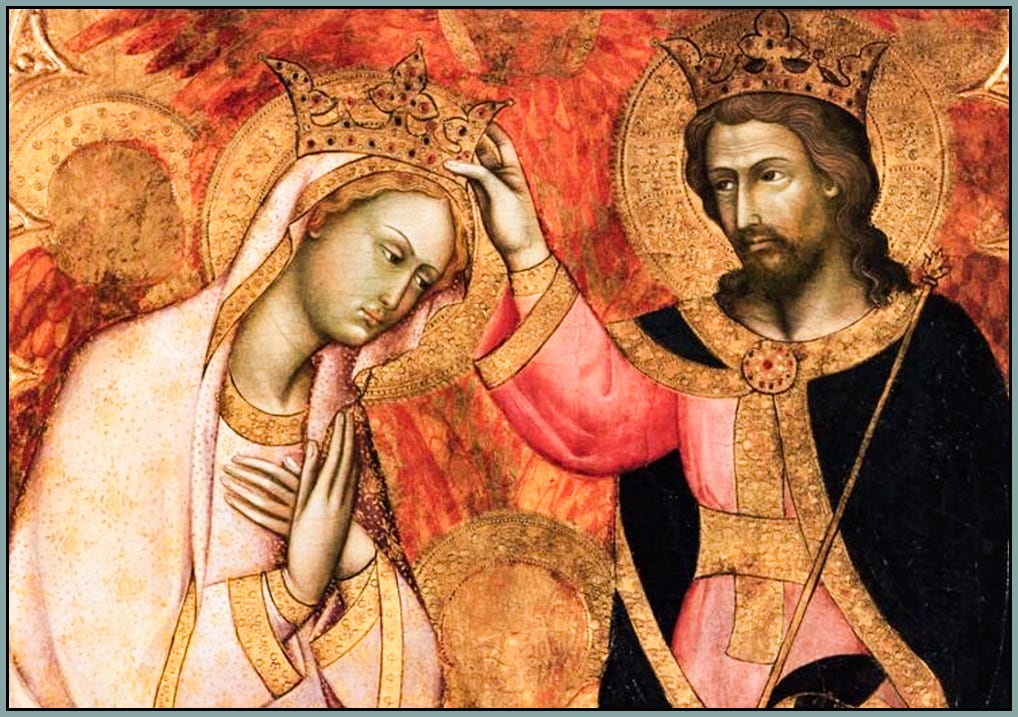

Let’s consider one more example: cwen, or “queen” in modern English, appears in both the “rule and government” category and the “supernatural” category, where it was used to refer to the Virgin Mary. This metaphorical link shows us that the Anglo-Saxon mind perceived and understood Mary as a heavenly version of an earthly queen. This may not seem too interesting, since the association still exists in modernity, but links in the metaphor map are starting points for further investigation: if we look more closely, we gain more insight.

First, medieval Englishmen actually lived under monarchical governance, and thus they were making a stronger statement by identifying the Virgin with real queens whose husbands were not just ceremonial kings but powerful, authoritative men expected to mete out justice and lead armies into battle. Thus, if the Virgin Mary was an Anglo-Saxon queen, then God was an Anglo-Saxon king, and that is definitely not the sort of God who, to borrow some unforgettable words from Peter Kwasniewski, is perceived as “a stuffed animal in bright fuzzy colors that tinkles ‘All Are Welcome’ when you squeeze it.”1

Second, cwen in Old English poetry could also mean “noblewoman,” which creates a somewhat different portrait of the Virgin as a heavenly member of medieval society. Rather than just a distant, idealized monarch at the pinnacle of the social pyramid, she is the paragon of female nobility—superior to but also closer to the people, an example of grace and goodness for all regions and communities, a woman of dignity and honor but also of the local castle, of the shire, of the land. (In the pre-Tolkien days, “shire” was an Anglo-Saxon term for an administrative district; instead of “shire” the conquering Normans used counté, ancestor of modern English “county.”)

Finally, one modern-English definition of “queen” is “something regarded as supreme, especially as the finest or most beautiful of its kind.” There is evidence for this usage in Old English, which suggests that in calling the Virgin Mary cwen, Anglo-Saxon folks understood her also as the most beautiful of all women. Or is it possible that the metaphorical connection flowed in the other direction? Maybe this usage entered into the English language because the Virgin, already imagined as a heavenly queen, was also honored by medieval Christians as the finest and greatest and most beautiful woman in history.

I hope this has been a useful introduction to a unique resource for exploring medieval thought. We’ll talk more about the Old English Metaphor Map, and metaphor in general, on Tuesday.

He continues: “At this point there is nothing left of religion as such, and certainly nothing that resembles a serious Christian culture in any way.” Agreed.

Sir Robert,

Once again, it is my privilege to be an early reader and commenter of and to your work. I will pass this on to my sister...fascinating.

I want you to know that timing means everything to me, and not 12 hrs before I read this I sent Emily Finley the daddy-to-daughter short story I wrote for my beloved adopted teenage daughter Gianna Rose. As the separation from my wife and family deepened and hardened during the COVID Interruption in 2021 I was inspired like never before. It was based on bedtime stories I used to 'conjure up' on the fly when tucking our three kids in bed after night prayers.

So, since I was moved deeply by Emily's last post on Castles and Knights, I send it to her so that maybe her kids might enjoy it.

NOW, I read this!!!

Your red, green and blue coding got me, because the intersection is WHITE, just like my logo in Substackland. This intersection point is where inspiration dwells.

You Sir Robert are on my Roundtable of Knights/Ladies to the MAST Project.

Steve Hermann leads the (M) Knights with his Incarnational Mysticism.

You and Amelia McKee share that station on the (A) quadrant because your depth of knowledge here is so profound.

Then there are the (S) and the (T) Knights/Ladies...and my list is growing.

The common thread?

The light, life and love that inform and permeate your efforts, for after reading and/or listening I am left with some combination of the principle fruits of the Holy Spirit: love, joy and peace.

My rambling point?

I'm alive both literally and figuratively because of the combined efforts of you all who 'feed me' daily and I am eternally grateful to you.

I, will remain an unaccredited seed planting hack. That is my lot in life and at 66 years old, I am at peace with it.

You all are the substantial food for this present moment of crisis and the vanguard of the future.*

*-IMHO, we are in a holding pattern at Rev.10-11. That is why we must keep repeating, "Get ready, Stay ready." That 7th Trumpet blast ends time and mystery.

Metaphor makes the real more real through the unreal.