Beware the Ides of March

A post in honor of Julius Caesar, with help from Shakespeare and Dante

If you’ve read a few posts from The Medieval Year, you already have some exposure to the Roman calendrical system. The Romans didn’t specify a day’s position within the month using a single number counting upward from one, as we do. Instead, the date was identified as a certain number of days before the Nones or Ides (of the current month) or the Kalends (of the following month). The Kalends was always the first day of the month; the Ides, marking the full moon, was the middle of the month (sometimes the 13th day, sometimes the 15th); and the Nones was the ninth day (counting inclusively) before the Ides. For example:

March 27th = ante diem sextum Kalendas Aprilis = sixth day before the Kalends of April

March 5th = ante diem tertium Nonas Martias = third day before the Nones of March

March 11th = ante diem quintum Idus Martias = fifth day before the Ides of March

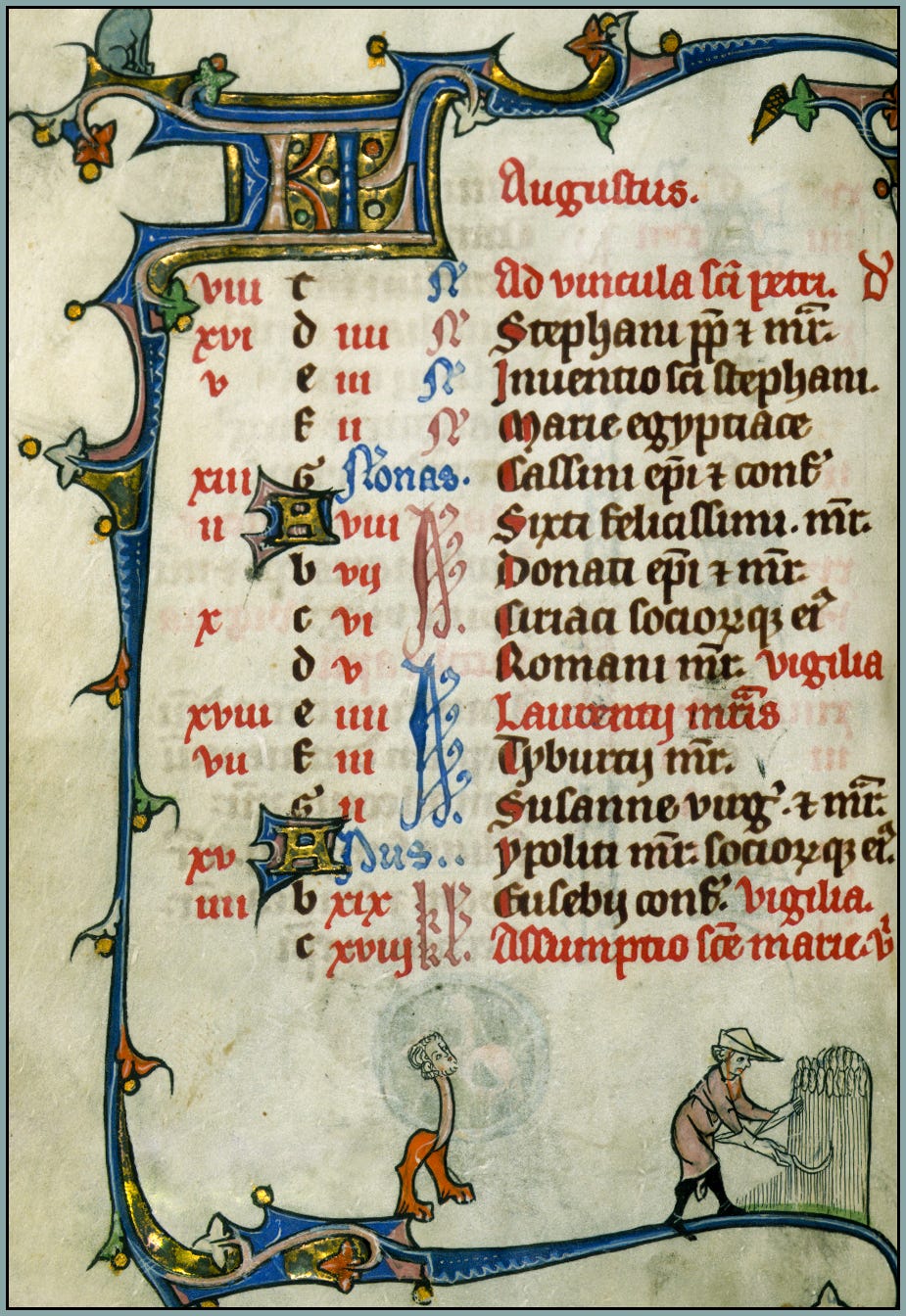

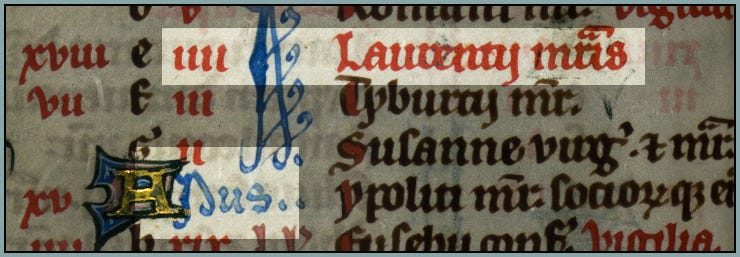

This scheme survived into the Middle Ages, where it was sometimes used for recording dates and very widely used in illuminated calendars. Including at least an embellished “KL” for “Kalends” in calendar pages was standard practice, but other elements are found as well. In the example below, from an early-fourteenth-century French codex, all elements of the Roman calendar are present: in addition to a golden, viny “KL” at the top, days are marked for the Nones (“Nonas”) and the Ides (“Idus”) in prominent blue ink, and note that the dates (in Roman numerals) count down as they approach these days. Thus, the feast of St. Lawrence—August 10th in modern nomenclature—is readily identified as the fourth day before the Ides of August.

Roman calendrical terminology faded out of popular consciousness long ago, and for most modern folks, dates expressed in the Roman style are thoroughly unfamiliar—except, that is, for the Roman version of yesterday, March 15th. It was a date that shook the world; many even today might recognize it, and this immortality we owe primarily to William Shakespeare.

SOOTHSAYER

Caesar.

CAESAR

Ha! Who calls?

CASCA

Bid every noise be still. Peace, yet again!

CAESAR

Who is it in the press that calls on me?

I hear a tongue shriller than all the music

Cry “Caesar.” Speak. Caesar is turned to hear.

SOOTHSAYER

Beware the Ides of March.

I wonder what proportion of current fourth-year college students could extemporize one or two clear, meaningful sentences on the life and death of Julius Caesar. I fear that the number would be small. I say this not to chide or disparage, but mostly just to mourn for a civilization that dug up its own roots and immolated them on the altar of the modern Self. We are all to varying degrees affected by the civilizational amnesia that naturally befalls when a society systematically dismantles authority, disdains tradition, and idolizes innovation.

Against this backdrop of contemporary indifference, the words of David Daniell, a distinguished English literary scholar, are all the more striking: the assassination of Julius Caesar, perpetrated on March 15th in the year 44 BC, used to be “the most famous historical event in the West outside the Bible.” But should we be surprised? The empire’s greatest man in the world’s greatest empire, betrayed by his friend and butchered by his own countrymen—is this not the stuff of legend? Is it not the very height of timeless drama and epic tragedy, to murder a man so monumental that even in death he somehow brought Rome to its knees, reaching as though from beyond the grave to crush the empire in his avenging hand?

Thou art the ruins of the noblest man

That ever livèd in the tide of times,

says Shakespeare’s Mark Antony to Caesar’s corpse, as the fell vision of civil war takes shape in his mind:

A curse shall light upon the limbs of men;

Domestic fury and fierce civil strife

Shall cumber all the parts of Italy;

Blood and destruction shall be so in use

And dreadful objects so familiar

That mothers shall but smile when they behold

Their infants quartered with the hands of war!

What followed, the historians tell us, was indeed a prodigious torrent of “blood and destruction”: political infighting, mass murder, internecine warfare, suicide.

And Caesar’s spirit, ranging for revenge,

With Ate by his side come hot from hell,

Shall in these confines with a monarch’s voice

Cry “Havoc” and let slip the dogs of war!

It all ended with the very thing the assassins sought to prevent, for the Roman Republic was dead, and a Roman Emperor was born.

My sense is that current attitudes toward Julius Caesar’s death, to the extent that such attitudes exist in the Age of TikTok, are ambivalent. We don’t like it when cold-blooded conspirators slaughter national heroes without even so much as a show trial, but then again, Caesar was a threat to that supreme and inviolable virtue of modern life: democracy, or what we might more accurately call quasi-democratic oligarchy, or what in some cases seems best defined as “the right to participate, through elections, in one’s own oppression.”

Medieval attitudes, on the other hand, were far less equivocal: Caesar was a heroic sovereign, and the assassins were villains. That was an age of (holy Roman) emperors and powerful monarchs, of feudal lords and strict social hierarchies, of lionized warriors and popes that commanded armies. It was an age when authority was sacred, punishments were harsh, and democracy was limited to an occasional peasant uprising. If a wise and mighty general like Julius Caesar leaned a bit too far toward autocracy, it was a minor fault and easily forgiven; the insolent men who treacherously killed him, on the other hand, were malefactors of the worst variety.

There was even a certain resonance between Iulius Caesar, slain hero of the Roman Empire, and Iesus Christus, slain Hero of the Roman Church. To what extent medieval Christians perceived Caesar as a secular-political Christlike figure is hard to say, but we do find a notable Christological aura surrounding the Julius Caesar crafted by Shakespeare—and let us not forget that Shakespeare was much closer to medieval culture than we are. This aura is strong, even arresting, when Mark Antony publicly eulogizes the murdered general, telling the gathered plebeians that “the word of Caesar might / Have stood against the world. Now lies he there, / And none so poor to do him reverence.” He feigns hesitation to read Caesar’s beneficent will: “Have patience, gentle friends. I must not read it. / It is not meet you know how Caesar loved you.” For if they were to know the fullness of his love, it would “inflame” them, and

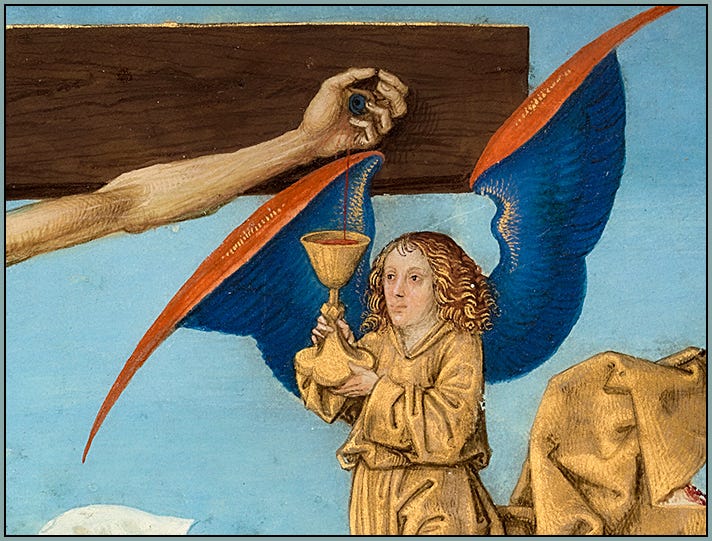

they would go and kiss dead Caesar’s wounds

And dip their napkins in his sacred blood.

The Irish poet W. B. Yeats called Dante “the chief imagination of Christendom,” and if we want to know how medieval Christians integrated Julius Caesar into their highly spiritualized, mystical-literary narrative of human history, we could have no better starting point than the Commedia. Dante finds the so-called “dictator” of Rome—armato con li occhi grifagni (“armored, with falcon eyes”)—in the limbo of virtuous non-Christians, an eternal destiny that he shares with illustrious company, including Homer (“lord of the song most high / who over the others like an eagle flies”); Aristotle (“master of those who know”); Aeneas, father of the Romans; Anaxagoras, who lived to contemplate the heavens; and Dante’s faithful guide, Virgil himself, “of all other poets the honor and light.”

However, the more compelling story of Caesar in the Commedia involves not the triumvir himself but those who murdered him. At the end of the Inferno, Dante and Virgil are in the Fourth Ring of the Ninth Circle of Hell. This is a place not of searing flames but of tormenting ice, and when Dante must look upon the monstrous Fiend who dwells there—“emperor of the dolorous kingdom,” now in his sin so hideous to behold—the poor poet is overwhelmed with horror: “I did not die, yet I was not alive.” Condemned to this foul and frozen swamp of agony, the deepest depth of the hellish pit, are those who betrayed their benefactors.

Only three damned souls are named in Canto 34 of Inferno. The first is Judas, who betrayed Jesus Christ. The other two are Brutus and Cassius, who betrayed Julius Caesar. Each will spend the rest of eternity in one of Satan’s three mouths, everlastingly crushed and torn by the grinding teeth of a ruined angel whose pride made him, like them, a traitor unto his lord.

If once he was beautiful as now he is ugly,

and yet raised his brow against his Maker,

we see why all sorrow proceeds from him.

If Solomon’s love poem is the Song of Songs, the Passion of the Incarnate God is the Story of Stories. It begins in Holy Scripture but does not end there, for no book can contain it. As a flood at once terrible and lovely, like the Virgin, it is ever overflowing from one text to another—sometimes to be found in unlikely places, where its presence, though perhaps in muted colors drawn, finds new pathways into the heart.

For Brutus, as you know, was Caesar’s angel.

Judge, O you gods, how dearly Caesar loved him!

This was the most unkindest cut of all.

For when the noble Caesar saw him stab,

Ingratitude, more strong than traitors’ arms,

Quite vanquished him. Then burst his mighty heart.

…

O, what a fall was there, my countrymen!

Then I and you and all of us fell down,

Whilst bloody treason flourished over us.

Don't St. Thomas's remarks in II Sent., d. 44, q. 2, a. 2 (beloved by liberals) imply some room for ambiguity in the medieval understanding of Caesar?

We can thank Woodrow Wilson’s demand in 1917 that a populace determine its own leadership for the modern view on colonialism and its antipathy towards monarchy. Of course, who really believes the people choose their leaders today?