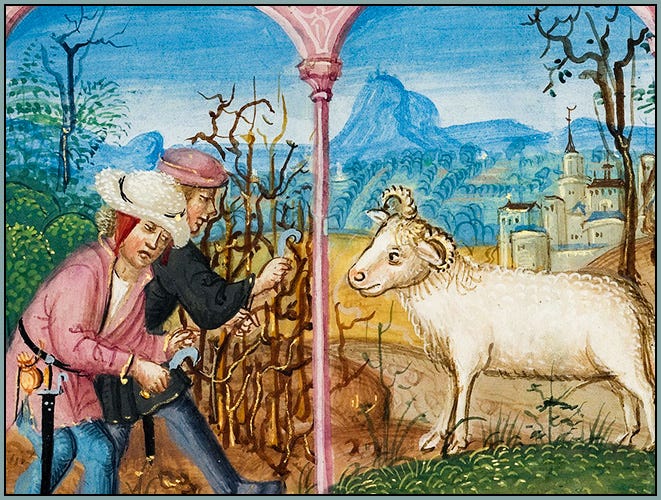

The Medieval Year, a regular feature of the Via Mediaevalis newsletter, gives us an opportunity to appreciate calendrical artwork from the Middle Ages, reflect on the basic tasks and rhythms of medieval life, and follow the medieval year as we make our way through the modern year. You’ll find helpful background information in these posts:

Of late years the Manilla rope has in the American fishery almost entirely superseded hemp as a material for whale-lines; for, though not so durable as hemp, it is stronger, and far more soft and elastic; and I will add (since there is an aesthetics in all things), is much more handsome and becoming to the boat, than hemp.

—Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

Long before the eighteenth century, when aesthetics matured into a distinct branch of Western philosophy, scholars of Antiquity and Christendom were already deeply invested in the art of rhetoric, which we might call the aesthetics of language. There is more to rhetoric than aesthetics, to be sure, and the ancients did not understand rhetorical discourse primarily in terms of beauty. For them, rhetoric was about persuasion, but we should endow this “persuasion” with richness and breadth of meaning, as Plato did when he said that rhetoric, the sister of poetry, is “the art of moving the soul by means of speech.” That which moves the soul—which enlightens, delights, inspires, consoles, impassions—is very often something possessing an excellence and perfection of form, and conveying radiance or harmony or elegance or nobility. In other words, it is very often something beautiful.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Via Mediaevalis to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.