Death and Life, Illuminated

The Medieval Year: Advent, and the Ides of December

The Medieval Year, a weekly feature of the Via Mediaevalis newsletter, gives us an opportunity to appreciate calendrical artwork from the Middle Ages, reflect on the basic tasks and rhythms of medieval life, and follow the medieval year as we make our way through the modern year. Please refer to the first post in this series for more background information!

John Harthan, former Keeper of the Library of the Victoria and Albert Museum, called the Grandes Heures (“Large Hours”) of Anne of Brittany “one of the most magnificent Books of Hours ever made.”1 I would go further and say that it is one of the most magnificent books—of any kind—ever made.

It’s December; it’s advent; it’s cold. Medieval Europeans see the vast tapestry of nature dying its temporary death, and the devotional practices of the Church lead their minds to somber thoughts of mortality and deprivation. The bleak winter may be a prelude to spring, but it is bleak nonetheless; the season of Advent may be a prelude to Christmas, but it was penitential nonetheless—for what thing can we truly cherish without feeling from time to time its absence, or even its opposite? Human nature is, after all, tragically inconstant. The poets knew it. Melville said it well:

Could it be possible that they robbed and murdered one day, reveled the next, and rested themselves by turning meditative philosophers, rural poets, and seat-builders on the third? Not very improbable, after all. For consider the vacillations of a man.

So did John Donne, a man whose spiritual life seems to have been as tempestuous as other people’s love lives:

I durst not view heaven yesterday; and today

In prayers and flattering speeches I court God:

Tomorrow I quake with true fear of his rod.

So my devout fits come and go away

Like a fantastic ague; save that here

Those are my best days, when I shake with fear.

Even life itself deforms and decays, coarsens and stiffens, if it is not preserved and renewed now and then by death: a paradox, indeed, that death should teach us how to live, but such is the wounded psyche of mankind. Christians of the Middle Ages understood this, and found ways to enrich their lives by imagining the moment when those lives would end. Even today we prepare for Christmas, that incomparable celebration of biological and spiritual life, with an old song of death:

Roráte cæli désuper, et nubes pluant justum.

Peccávimus, et facti sumus We have sinned, and we are become tamquam immúndus nos, as one that is unclean, et cecídimus quasi fólium univérsi: and we all have fallen, as a leaf: et iniquitátes nostræ and our iniquities quasi ventus abstulérunt nos: like the wind have carried us away: abscondísti fáciem tuam a nobis, thou hast hid thy face from us, et allisísti nos and thou hast crushed us in manu iniquitátis nostræ. in the hand of our iniquity.

Anne of Brittany was the queen of France not once but twice, because she was married to not one but two kings of France (successively, I mean … not at the same time). As the wife of Charles VIII, she reigned from 1491 to 1498; as the wife of Louis XII, she reigned from 1499 until her death in 1514. We are indebted to her patronage for a manuscript whose beauty is immortal; five hundred years later, it captivates us.

In the spirit of Advent—“we all have fallen, as a leaf”—let us meditate briefly on these three monarchs, who serve as a sobering reminder of life’s brevity and fragility. Charles VIII’s untimely end is the most shocking example of the three. As the king of France in the late fifteenth century, he was, at the moment of his death, one of the most powerful people on earth; he must have looked well-nigh invincible to the ordinary folk who caught a glimpse of him. One day, while rushing to a tennis match that he was eager to watch, he struck his head on the lintel of a low doorway, suffered a concussion, and died. He was twenty-seven years old.

Anne—born into high nobility, made the wife of kings, and no doubt given the best medical treatment available at the time—died from an attack of kidney stones at the age of thirty-six.

Louis XII was sickly and made it only to age fifty-two, and we can extend this theme to his third wife, Mary Tudor, sister to yet another immensely powerful man, Henry VIII of England. She died at age thirty-seven from health problems that the doctors of the time couldn’t even identify much less treat; maybe it was cancer, maybe tuberculosis, maybe even grief over her brother’s cruel treatment of Katherine, his faithful wife.

Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell,

And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well

And better than thy stroke; why swell’st thou then?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally

And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

—John Donne

Let’s take a look at the Grandes Heures calendar pages, which include the labor of the month, for the two previous months—first, because many new subscribers have joined us recently, and second, because the artwork is simply stunning.

The labor for October is preparing the soil and sowing winter wheat or rye. Notice the swans and the charming village, on the right.

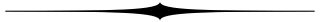

In November, folks are busy getting the hogs fattened up. Let us never underestimate the economic and sociological importance of ensuring an abundant supply of sausage for winter.

In December, the swine must fulfill their destiny (as medieval society understood it), and thus do we return to the theme of today’s post. The Middle Ages was an era of many things; it was emphatically not an era of vegetarianism (except as an element of monastic asceticism).

The artist of the Grandes Heures depicted the hogs’ demise with such skillful naturalism that I find the painting somewhat disturbing. Out of consideration for those who don’t want to look at dead and bleeding animals, I’ve made the image below very small. Those who are comfortable with such things can click to enlarge.

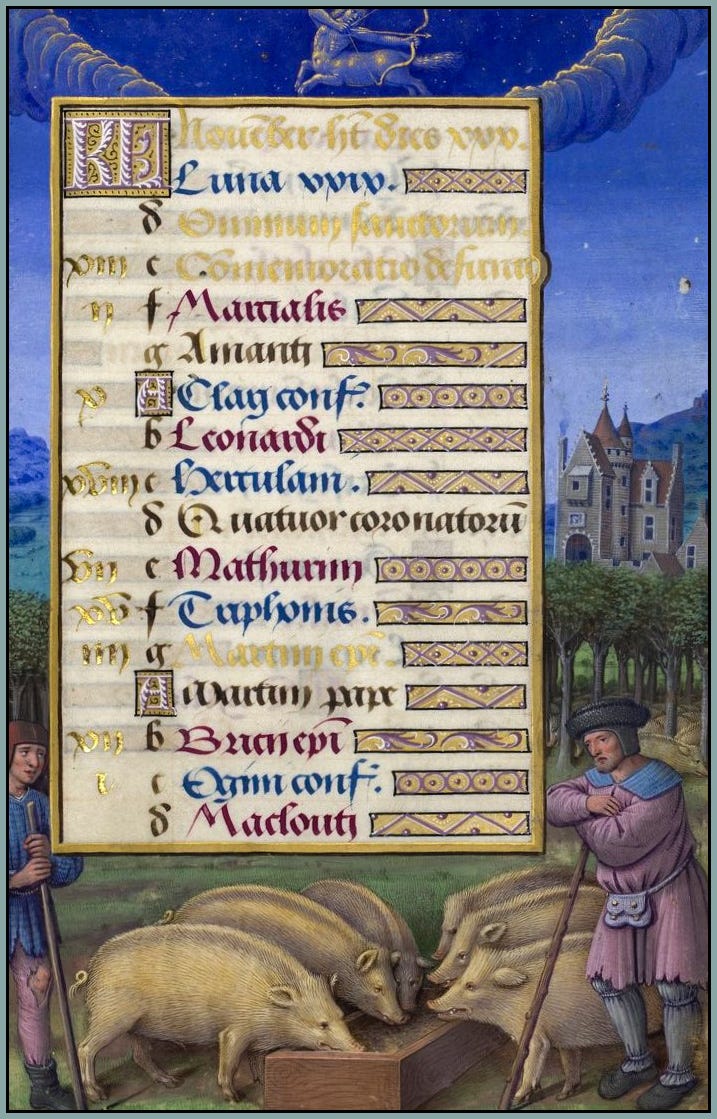

The artistic magnificence of the Grandes Heures owes much to the plants and small creatures that inhabit its extraordinary marginal decorations. Perhaps your world, like mine, is becoming less green and less lively as the leaves, flowers, and insects slowly succumb to winter. It is in such times as these that we are all the more grateful for fine art, which so often supplies what nature lacks, or reveals what the senses do not perceive.

John Harthan, The Book of Hours. Thames and Hudson (1977), p. 128.

Robert, thank you for brightening up this bleak South Texas morning.

As I read this and reflected about my own responsibilities concerning bringing color to families and their homes (I am the sales associate who kinda runs the paint department of a major building supply company in Texas) I see how COLOR is fundamental to spiritual and emotional well-being.

You showcased:

the Father's and Our Lady's BLUE,

the Son's RED (in a negative example provided by the poor pigs). This speaks to the saving power of Jesus Christ's Precious Blood.

the Holy Spirit's GREEN with the vegetation that springs from winter's grave as nourishment for the next generation of life (and love).

I have a computer screen that is used to develop paint colors and dispense tinting and as a background I have a black screen with three interlocking Borromeo Rings to teach customers how full blue, full red and full green LIGHT is perceived by the cones of our eyes as pure, WHITE LIGHT.

Call it subconscious or covert evangelization or not. I haven't been fired yet.

Praise the Holy Trinity, undivided unity, Holy God, Mighty God, God Immortal be adored.

Such luminous images, and so full of life! Elizabeth heavy with child. The swine in abundance being prepared for slaughter. The bugs, butterfies and caterpillars among the plants and fruits. The exquisite beauty of the Virgin. Such a gift!