“Desdemona Is Shakespeare’s Word for Love”

Medieval culture and the transformative power of allegory

[To detract from the honor of parable] would be rash, and almost profane; for, since religion delights in such shadows and disguises, to abolish them were, in a manner, to prohibit all intercourse between things divine and human.

—Francis Bacon

Key to Shakespeare’s literary genius was an ability to create characters who are both allegorical types and real people, at the same time. How exactly he did this, I cannot say. There is a point at which his poetic craftsmanship is beyond the reach of critical method—beyond, perhaps, the reach of the analyzing mind. As with traditional Christian liturgy, one must simply acknowledge that an irreplaceable thing has somehow been wrought, and that its proper effect, when rightly received, is to delight, to captivate, to transform. And as with the preaching of the God-Man, one must marvel at the mysterious power of words that tell two stories at once: “And with many such parables spoke He the word unto them, according as they were able to hear it: and without parable spoke He not unto them.”

If I were to evaluate the emotional intensity, narrative elegance, and thematic richness of famous texts relative to their length, I might conclude that the allegory of the Prodigal Son is the greatest story ever told. And have you noticed that its characters—the father, the son, the brother; Mercy, Penitence, Self-righteousness—are both strikingly real and perfect embodiments of a higher truth? Shakespeare was not the first to achieve masterful harmony between realism and allegory, and we should be mindful of the possibility that he learned a great deal—not just about religion, but about telling stories—from Jesus Christ.

There has been some heated controversy of late about using the term “magic” in a positive sense. I confess I am quite lost as to the motive for the opposing party’s condemnation: the non-occult usage of the word “magic” has been part of the English language for four hundred years; it’s right there in the dictionary for all to see. Indeed, we should be grateful that something evil like sorcery can at least help us to discuss something immensely good that operates, according to human nature’s limited and metaphorical way of thinking, in a similar fashion. I, for one, can think of no better word to convey the extraordinary results of Shakespeare’s creative labor: it is magic, and he, like his creature Prospero, was a magician. How fitting, then, that the first recorded use of the word in its figurative sense—“remarkable influence producing surprising results; an enchanting or mystical quality; exceptional skill or talent”—comes from Shakespeare himself, in The Winter’s Tale: “O royal piece,” says repentant Leontes to a statue that, though depicting his virtuous wife, quite clearly alludes to the Virgin Mary, “there’s magic in thy majesty.”

For as hieroglyphics were in use before writing, so were parables in use before arguments. And even to this day, if any man would let new light in upon the human understanding, and conquer prejudice, without raising contests, animosities, opposition, or disturbance, he must still go in the same path, and have recourse to the like method of allegory, metaphor, and allusion.

—Francis Bacon

Over the past two weeks we’ve been thinking about the languages of medieval life. First we explored medieval liturgy, which in western Christendom was joyfully united to Latin. Then we considered the special value of the vernacular, taking Julian of Norwich’s Middle English as a representative—and beautiful, and enlightening—example. Today we’re continuing this line of inquiry, but now we’re broadening the idea of language from specific systems of communication into general modes of communication, and one of the modes that had a special role in medieval culture was allegory.

Pre-modern societies gravitated to allegorical thought and expression more naturally than modern folks do. In my simplified view of a complex historical process, allegory became somewhat unfashionable in early modernity as Renaissance aesthetics emphasized realism and sophistication—though the quotes from Francis Bacon, who died in 1626, show that its exceptional significance in human culture was still recognized. Allegory survived the upheavals of the seventeenth century, thanks in large part to Milton, but it was losing momentum. Next comes the neoclassical period; with its emphasis on rationality, restraint, and lofty imitation, it was not fertile ground for allegorical thinking. The Romantics revived an interest in symbolism, but not really in medievalesque allegory; the two are related, but the latter looks “reductive” and “mechanical” when viewed through a Romanticist lens. There wasn’t much room for allegory in the novelistic realism of the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century, culture more or less went off the rails. It hardly matters if, after the dust cleared, some of the wreckage was carried off in an allegorical direction, because by this time the strongest influence on human thought—by far—came from the proliferation and eventual ubiquity of modern science, industrial manufacturing, and electronic technology.

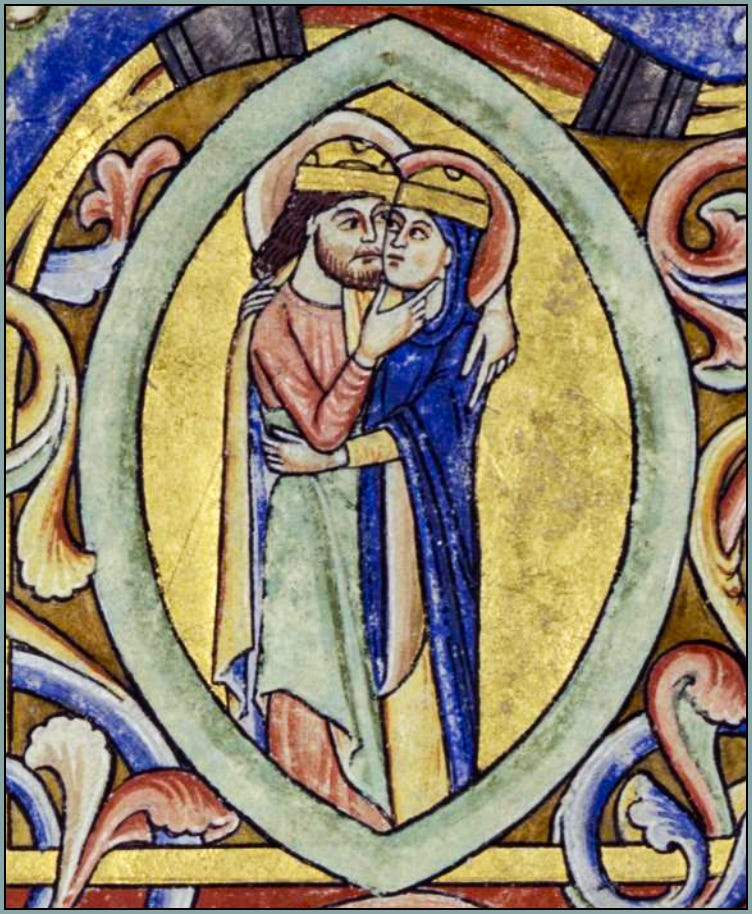

Medieval Christendom’s devotion to the allegorical mode is inseparable from its devotion to the sacred literature of the Bible, and the allegorical heart of the Bible is the divine love poem that we call the Song of Songs. All the images in this post are visual depictions of a story about two human lovers that for medieval Christians was also about Christ and His bride, the Church.

When it comes to the paradoxical feat of making characters both deeply real and powerfully allegorical, I’ve found no other modern author who succeeded as Shakespeare did. Dickens and Melville come to mind as artists who worked in a similar mode, but few if any of their characters have affected readers, and culture more generally, as Shakespeare’s have—and let’s not forget that a Shakespearean character must take shape within the confines of a three-hour play consisting only of speech and a few bare-bones stage directions. Moby-Dick is a fifteen-hour read filled with descriptive narration, and still, Captain Ahab doesn’t resonate in the Western imagination like King Lear does.

In defense of modern authors—by which I mean “late modern,” since Shakespeare was “early modern”—one could point out that the objective was different. Hemingway said this:

When writing a novel a writer should create living people; people not characters. A character is a caricature.

Hemingway, come now. You should know better than this, and by the end of your career maybe you did know better—that piece of dubious advice is from Death in the Afternoon, first published in 1932. But Hemingway is really just acting as a spokesman for the aspirations of so-called “realism,” which was on the rise in eighteenth-century novels, reached its apogee with the Victorians, and remained dominant into the twentieth century. (It is perhaps not widely recognized that even literary Modernism, despite its aura of strangeness and experimentation, was informed by artistic realism. Virginia Woolf envisioned Modernist fiction as a realist representation of the interior world—that is, as narrative which brings the reader closer to the “real life” of the human psyche, or as she said, to the “quick of the mind.”)

Realism, in both the visual and the verbal arts, has animated numerous masterpieces. A wholesale rejection, as far as I’m concerned, is out of the question. But the “realist” project (here I’ll bring back the scare quotes, to sharpen the point) has a fatal flaw: the “real” implied in “realism” tends to be observable, meaning physical and psychological, reality. What about the medieval realities—moral, spiritual, symbolic, eschatological—that were essential to social order, cultural flourishing, and mental health in pre-modern Europe? They are pushed into the background, or maybe even booted off the stage.

Thus, “realism” makes art more “real” under the assumption that “reality” is composed primarily of physical objects and human beings. However, that sort of reality wasn’t good enough for medieval poets and painters, who lived in a society where the visible world was subordinated to, and ennobled by, and dependent upon, the invisible world. They sought, therefore, to build bridges between these two worlds, and allegory was a means of doing that. For them it was not just a literary device, not a merely imaginative excursion. Rather, allegory gave man what he truly needed to understand himself, his world, and his eternal destiny. Realism has been around for a long time; it comes with a lot of baggage, and we’re all carrying it. Modern folks like us, if we want to rediscover reality, must learn to think allegorically.

The title of this post comes from an essay on Othello by Alvin Kernan, a distinguished scholar who taught at Yale and Princeton. He would not deny for a moment that Desdemona is a complex character drawn with all the fine contours of human thought and feeling; indeed, as the process of technological zombification continues apace, her vibrant humanity is increasingly a reproach to those who actually are alive and were created by God instead of an English dramatist. Nevertheless, Kernan recognized that Desdemona also is “Shakespeare’s word for love.” When you put everything together, and meditate on the play as the unified artwork that it is, you see that Desdemona is a poetic discourse on the nature of true love—in other words, that she is an allegorical type. In a medieval play, her name could have been Love. Shakespeare’s name for her, which by the way he simply inherited from his principal source text, is more subtle but still charged with significance: Desdemona means (in Greek) “ill-fated,” which perfectly expresses her particular destiny within the play, but which also names those who choose to love boldly in this vale of tears and sin: “If the world hateth you, ye know that it hath hated Me before it hated you…. If they persecuted Me, they will also persecute you.”

We can only speculate as to why Shakespeare developed an ability to weave his characters, in so deft and balanced a fashion, from both realistic personality and allegorical typology. Nonetheless, there is a remarkable correspondence between this aspect of his writing and the general outline of his biography: Shakespeare spent his most formative years in a liminal space between late medieval culture and early modern culture. The second half of England’s sixteenth century was a time when new mentalities and Renaissance art were thriving. Modernity was in the air—the London air was especially thick with it—and Shakespeare was breathing it all in. But his hometown was far from London, and out there in the West Midlands there was plenty of medieval breeze still blowing through the fields and forests. The mixture that formed the mind of the young Shakespeare—allegory from the medieval past, realism from the modern future—seems to have formed his characters as well.

We cannot know all the subtle ways in which Shakespeare may have encountered the allegorical thought and culture of his medieval ancestors. We can, however, be confident that he directly experienced one important holdover from the allegorical art of the Middle Ages. It was art of an especially vivid and memorable kind, and it may have strongly influenced his life, both as a Christian and as a dramatist. It is called the “morality play,” and it will be our topic of discussion on Tuesday.

I needed to read this just now Robert.

You wrote, "What about the medieval realities—moral, spiritual, symbolic, eschatological—that were essential to social order, cultural flourishing, and mental health in pre-modern Europe? They are pushed into the background, or maybe even booted off the stage."

Divine Providence was at work when The Third Wave by Alvin Toffler (1980) 'jumped' into my hands four days ago at a rural lending library as if commanding, "READ ME!"

Your quote is precisely descriptive of what occurred when the First Wave was beginning to be challenged by the Second Wave.

Now we are experiencing the surmounting of the Second Wave by the AI fueled Third Wave.

There are chilling conclusions to the impending cresting that is dwarfing our feeble breakwater.

I hope to try to get a men's conference here in Texas to discuss this situation and raise awareness.

I'm only 150 pages in but it is worth the read for perspective.

This was, as usual, beautifully written and philologically insightful. You hit the mark when you wrote, “Modern folks like us, if we want to rediscover reality, must learn to think allegorically.” I was going to say something about the chances of this happening in a large way in today's era, but I won’t. I want to be positive.(!)