Modern Perspectives on the Problems of Democracy

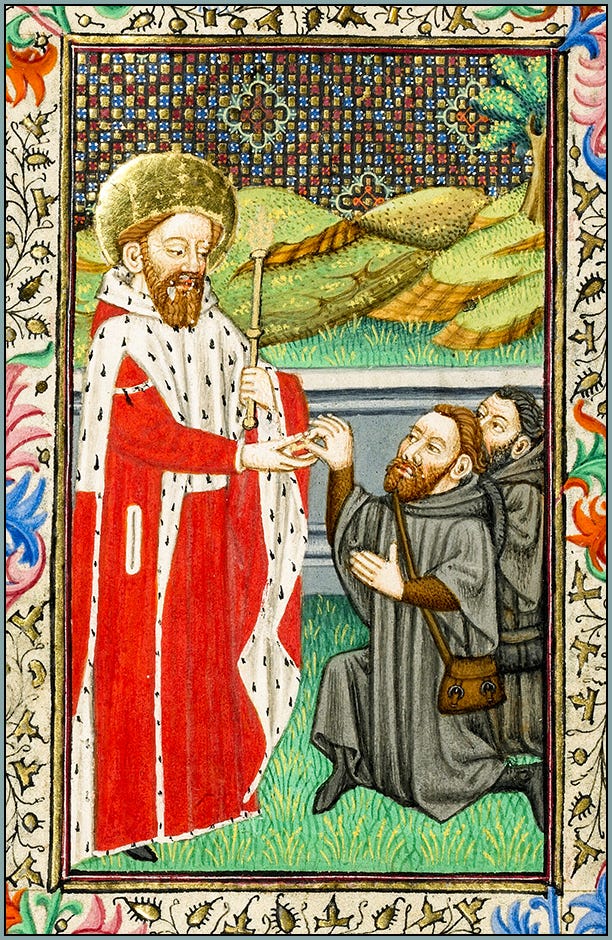

The Age of Faith was an age of monarchs and heirs, not voters and elections

We should not listen to those who are in the habit of saying that the voice of the people is the voice of God, since the riotousness of the multitude is always close to madness.

—Alcuin, medieval scholar and theologian (d. 804)

As you probably have noticed by now, modern society exhibits various features that I’m not particularly enthusiastic about. In many cases, though, these features don’t really surprise me, insofar as they follow logically from the disordered tendencies of human nature in its fallen state. Unruly appetites, imbalanced emotions, darkened intellects, hubristic ambitions, weakened bodies—these things have been throwing wrenches into human civilization for an awfully long time. The historically unprecedented tribulations of modernity are the result of, first, inheriting the wreckage of the past while abandoning its wisdom, and, second, creating cultural and technological conditions that are for our disordered tendencies what strong winds, high temperatures, underfunded fire departments, and ammunition depots are for a burning city.

However, one thing about modernity that I do find rather surprising is its infatuation with democracy. Honestly, I’m not trying to sound like some sort of cantankerous monarchist. As far as I can tell, no political system will produce good governance in a society that is so religiously, morally, artistically, and psychologically fragmented as those of the modern West. Thus, on a purely practical level, I’m fine with democracy, or at least with the status quo that most people call democracy but some might call an electoral version of oligarchy, plutocracy, technocracy, gerontocracy, pathocracy, etc. But on a theoretical level democracy is so manifestly problematic, in some ways even with respect to monarchy, that I really do wonder how it became deeply rooted in, and inseparably bound to, the ideologies and aspirations of the late modern period. Consider the following:

“The people” can be very wrong

As wise political thinkers have long recognized, the so-called will of the people is a highly unreliable basis for any type of governmental action. It’s hard to discuss this issue without offending our egalitarian sensibilities, but seriously, not everyone has the education, judgment, ethical integrity, temperament, etc. proper to those who will be entrusted with the welfare of the commonwealth and the lives of its members. If you’re a brain surgeon, I don’t think you should be teaching my Shakespeare class, and I in turn should not be anywhere near an operating room. That’s just common sense. But why are both of us expected to participate in governance as though we have expertise in law, economics, and international diplomacy?

Elections = (often egocentric) ambition

Running for high office is a voluntary act that tends to be costly, time-consuming, physically dangerous, psychologically stressful, fraught with temptation, and likely to end in failure. Thus, elections inevitably favor highly ambitious individuals—and is extreme personal ambition really the sort of thing that is likely to make a good leader? Is this the sort of trait typically accompanied by altruism, principled realism, moderation, and scrupulous adherence to the laws and customs that constrain the exercise of power? Should we be surprised if democratic presidents, prime ministers, and lawmakers have become notorious for corruption, moral dysfunction, and megalomania? Think about how different this is, at least in theory, from hereditary monarchy: power is bequeathed to an heir regardless of his or her personal interest in exercising it, rather than awarded to a candidate who was hungry for it and managed to acquire it by winning a race—our own democratic terminology shows that elections are perceived as a competition, with the winner taking political power as the prize! Newly crowned Christian monarchs could be very flawed and still at least recognize that their power, made of equal parts privilege and duty, was received.

Elections = money

Elections also ensure that money, sometimes vast quantities of it, will get hopelessly entangled in the political process. Campaigns are inherently expensive, and the trend is always toward more expense, because if you’re running for office and you have money, the easiest way to get ahead of your opponents is to spend it: travel more, advertise yourself more, propagandize more, “compensate” “collaborators” more, and so forth. Could there be any better way to achieve the utter ruination of politics? The Bible says that “the love of money is the root of all evil”!

The throne is empty

A question as fundamental as “who’s in charge?” has no clear answer in an electoral democracy. Is it the elected officials? If so, “democracy”—from the Greek demos (“the people”) and -kratia (“power, rule”)—exists only during elections and referenda. Is it the appointed ministers and hired bureaucrats? If so, we have a problem, since they’re not elected. Is it the people? If so, do they hold power individually, or as a collective? If as a collective, is power somehow divided equally among all voters? Or among all citizens? And how do they exercise this power? I live in a democracy, and I have a burning desire to abolish the “daylight-saving” (whatever that means) time changes that needlessly disrupt my biological rhythms in the spring and the fall, every year of my life, with no end in sight. Why do I feel utterly powerless to accomplish this, especially considering that about 70% of “the people” in my country also want to see the time changes abolished?

Though power in medieval societies was distributed in complex ways, the monarch was understood by all to be the ultimate temporal authority, and perhaps more importantly, he or she possessed and occupied the symbols of power—the crown, the scepter, the throne. The French political philosopher Claude Lefort (d. 2010) wrote insightfully on the symbolic dimension of power and its strange absence in modern democracies:

Under the monarchy, power was embodied in the person of the prince. This does not mean that he held unlimited power. The regime was not despotic. The prince was a mediator between mortals and gods…. Being at once subject to the law and placed above laws, he condensed within his body, which was at once mortal and immortal, the principle that generated the order of the kingdom.

With this deeper understanding of the monarch’s role in a medieval society, we discern

the revolutionary and unprecedented feature of democracy. The locus of power becomes an empty place…. The locus of power is an empty place, it cannot be occupied—it is such that no individual and no group can be consubstantial with it.1

The result, as I observed above and as Lefort expressed succinctly, is that in a certain sense, power in a democracy “belongs to no one.”

The two things I want to connect are, on the one hand, the people, who are composite, multiple, and conflictual, and, on the other, power, which belongs to no one. These are the two things that we must understand, I believe, to grasp democracy’s nature.2

Democracy = ?

Despite using the word repeatedly in the foregoing paragraphs, I’m not sure what “democracy” even means—and that is by design! As George Orwell observed,

in the case of a word like democracy, not only is there no agreed definition, but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides. It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic we are praising it: consequently the defenders of every kind of régime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using that word if it were tied down to any one meaning.3

Thus, we have a political system with grave, glaring, virtually irremediable defects and a track record that in some ways is simply abysmal. And yet, it is now a sacrosanct and almost universally acclaimed feature of modern societies, to the extent that someone like Jane Addams, a social reformer and Nobel Peace Price winner who died in 1935, could say that “the cure for the ills of Democracy is more Democracy.” Perhaps that is true, insofar as modern societies, having fashioned themselves into historically anomalous entities, are utterly incompatible with forms of government that worked well in the past. If the West has reached a point at which the only conceivable alternative to democracy is secular dictatorship or technocratic totalitarianism, by all means, give me more democracy! But at the very least, we should recognize that modern political systems are not good just because they are democratic, and that medieval political systems were not bad just because they were monarchical.

Politicians, unelected bureaucrats, and capitalists have significantly more power and control over your lives than a medieval king over a peasant. The king had no authority … to legislate new laws or manipulate his people’s economy, politics, and rights. There was no legislation! The law was practiced and enshrined over many generations, and it was the king’s duty to protect and uphold it.

—Jeb Smith, author of Missing Monarchy: What Americans Get Wrong about Monarchy, Democracy, Feudalism, and Liberty

I am certainly not the first modern person—by which I mean someone educated in a modern environment and thoroughly accustomed to modern lifestyles—who has questioned the purported excellence of democratic governance. Voltaire, of all people, believed that the only rational form of government was enlightened monarchy:

“Why is almost the whole earth governed by monarchs?” Voltaire asked. “The honest answer is because men are rarely worthy of governing themselves…. Almost nothing great has ever been done in the world except by the genius and firmness of a single man combating the prejudices of the multitude…. I do not like government by the rabble.”4

I’m not sure who exactly “the rabble” are, but the medieval “rabble”—that is, the hard-working, tradition-loving peasantry whose keen minds and leathern hands built Europe into Christendom—probably possessed more real-life political wisdom than Voltaire did.

Two much more recent examples come from an essay by Professor Todd DeStigter, who summarizes the views expressed by the political theorists Slavoj Žižek and Jodi Dean. For Žižek, democracy is “an empty signifier” that “stands for nothing except its own deliberative processes” and impedes meaningful change. For Dean, democracy is a “neoliberal fantasy” that turns political responsibility into endless discussions that just reinforce the status quo (case in point: the daylight-savings time changes!).

I’ll conclude with some statements that really are quite shocking—or at least, you might find them shocking when I tell you who wrote them.

“Democracy has never been and never can be so durable as Aristocracy or Monarchy. But while it lasts it is more bloody than either.”

“The Athenians grew more and more Warlike in proportion as the Commonwealth became more democratic.”

“It is in vain to Say that Democracy is less vain, less proud, less selfish, less ambitious or less avaricious than Aristocracy or Monarchy. It is not true in Fact and no where appears in history.”

“Remember Democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes exhausts and murders itself. There never was a Democracy Yet, that did not commit suicide.”

Those words are found in a letter written in 1814 by John Adams, Founding Father and second President of the United States of America.

As I’ve already indicated, the practical implications of this essay have nothing to do with contemporary politics—any attempt to shift away from democracy in its current form would surely lead us to something worse. The importance, rather, is in avoiding the cognitive dissonance, perhaps even the spiritual danger, of seeing the Age of Faith as a time when supposedly humane, enlightened political systems (democracy) were unheard of and supposedly oppressive, primitive political systems (monarchy) were pervasive. If the preeminently Christian culture of the Middle Ages bore such wondrous fruit in the domains of art, literature, philosophy, monasticism, personal holiness, and social wholeness, we must also be willing to believe that it approached—as closely as poor sinners can—to the ideal methods and structures of governance.

On Tuesday, we’ll continue this discussion by taking a closer look at medieval monarchy and the doctrine of the Two Swords.

Claude Lefort, Democracy and Political Theory, translated by David Macey. University of Minnesota Press (1988), p. 17.

“Trial by Politics: A Conversation between Pierre Rosanvallon and Claude Lefort,” published in Books and Ideas.

George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language.”

Robert Massie, Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman. Random House (2011), p. 335.

It's also interesting that for most of history, democracy did not mean will of "the rabble" but rather the will of a land owning cultured class. I could be wrong, but I don't think pre-industrial people ever thought giving literally everyone over the age of 18 a vote was desirable.

Couldn't agree more -- it seems to me that governing a nation is practically just another level of the family, and what family can have any peace or order without headship resting in one father?

And I also couldn't agree more with your thoughts on Daylight Savings, sick and tired of it!