No Beginning, No End

The circle of time in the pre-medieval world

Thus ebbs and flows the current of her sorrow,

And time doth weary time with her complaining.

She looks for night, and then she longs for morrow,

And both she thinks too long with her remaining.

Short time seems long in sorrow’s sharp sustaining;

Though woe be heavy, yet it seldom sleeps,

And they that watch see time how slow it creeps.

—Shakespeare, “Lucrece”

On Sunday, we began our journey into medieval temporality by examining the linear, teleological conception of time that has accompanied and powerfully influenced post-medieval culture. Today we will consider the opposite end of the theoretical spectrum: time as an endless cycle of repetition and renewal. However foreign or unscientific this cyclical model of time may seem to those educated in the modern West, this is truly how time and human history were understood in the ancient civilizations of India, Greece, and, perhaps to a lesser extent, Rome.

In ancient Indian culture, cosmic and human existence were so thoroughly cyclical that there was essentially no notion of history as we now understand it. The Indian historian R. C. Majumdar declared that

except Kalhana’s Rajatarangini, which is merely a local history of Kashmir, there is no other historical text in the whole range of Sanskrit literature which … may be regarded as history in the proper sense of the term.

And this is despite the fact that “there is hardly a branch of human knowledge or any topic of human interest which is not adequately represented in Sanskrit literature.” Think of all the history books that nowadays you could find in just one university library. In ancient India, the genre did not exist. Try to imagine how massively different your experience of life would be if all those books, and all the knowledge that they contain, simply disappeared—stories of the past, unknown; that which came before, not spoken of; the origin and evolution of the world you now inhabit, forgotten. Time was a cycle, life was a cycle, and history, as another scholar explained, was a dangerous illusion from which man, in seeking wisdom, must free himself.

The situation in ancient Greece was less extreme. First of all we have Greek mythology, which was deeply interested in the origin of things and the crucial events—the triumph of Zeus, the Golden Age of the Mecone plain, Prometheus and the fire, Pandora and the box—that helped to explain the precarious and paradoxical nature of man’s existence.

Furthermore, the supreme glories of Greek literature, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, were poetic narratives clearly rooted in a sense of historical reality. Homer and his works never could have attained such immense esteem if the ancient Greeks had dismissed history as an illusion that obstructs the path to wisdom. For example, in one short passage from the Poetics, Aristotle refers to both Homer’s greatness and the historical nature of his subject matter:

Herein … we have a further proof of Homer’s marvelous superiority to the rest. He did not attempt to deal even with the Trojan war in its entirety, though it was a whole with a definite beginning and end.

We must also recall, however, that Aristotle viewed poetry as nobler and more edifying than historical literature:

The poet and the historian differ not by writing in verse or in prose…. The true difference is that one relates what has happened, the other what may happen. Poetry, therefore, is a more philosophical and a higher thing than history: for poetry tends to express the universal, history the particular.

And despite the sense of history that we see in Greek literature, ideas of epic cyclicality were widespread in ancient Greece. In the Statesman, for example, Plato mentions a belief in cycles of regeneration that govern the existence of the cosmos and of the human race:

These earliest forebears were the children of earthborn parents; they lived in the period directly following the end of the era of the earthborn, at the close of the former period of cosmic rotation and the beginning of the present one.

Also in the Timaeus, we read of cataclysmic events after which humanity must “begin all over again like children, and know nothing of what happened in ancient times.” Aristotle, in the Metaphysics, similarly alludes to history as a cycle in which human civilization repeatedly flourishes and dies back, evoking the life-rhythms of a deciduous forest rather than modernity’s forward march of continual scientific advancement: “probably each art and each science has often been developed as far as possible and has again perished.”

Again, let’s take a step back and think about what this really means. Plato’s and Aristotle’s statements, taken as mere cosmology or anthropology, may appear outlandish to us. But we must look beyond the surface of their words and seek the underlying principles; they were, after all, lovers of wisdom, not scientists in the modern sense. What I see in the cyclical time of the ancient Greeks is sensitivity to the enticements, and protection from the dangers, of linear time. I see a warning against the idolization of progress—that is, against excessive admiration for our cultural accomplishments; against quasi-religious faith in our potential for self-made magnificence; against the hubristic belief that we are ever surpassing what has come before, that our new things are necessarily better things, and that the principal means of solving humanity’s problems is innovation rather than restoration.

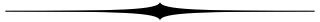

The ancient Roman understanding of historical time shows a blend of linear and cyclical modes, and it leads us, through St. Augustine, to the multifaceted and highly spiritualized temporality of the Middle Ages.

First let’s consider Stoic philosophy. Stoicism originated in Greece in the third century BC and was by no means a universal belief system. Nevertheless, it was well known in Rome and left a lasting impression on Roman culture. Stoic cosmology proposed a model of history that is cyclical in the extreme; David Sedley, a professor of ancient philosophy at Cambridge, explained it in this way:

The Stoic world is a living creature with a fixed life cycle, ending in a total “conflagration” [i.e., destruction by fire, or as some believed, by water]…. Being the best possible world, it will then be succeeded by another identical world, since any variation on the formula would have to be for the worse. Thus the Stoics arrive at the astonishing conception of an endless series of identical worlds—the doctrine of cyclical recurrence, according to which history repeats itself in every minute detail.

No beginning, no end: for Stoics, historical time was an endless cycle of self-destruction and identical re-emergence. Does this sound absurd to you? It sounds absurd to me. And yet, it was believed by intelligent members of a famously erudite civilization.

As a counterpoint to Stoicism, however, we have Roman mythology, which includes the notion of a Beginning, when the world emerged out of chaos. We also have Virgil’s Aeneid; though not at all devoid of cyclical temporality, it does convey a notably teleological view of history—there is a sense that the poem’s epic historical narrative moves steadily from origin toward completion. And interestingly, both of these endpoints can be identified with individuals: what begins in Aeneas is fulfilled in the emperor Augustus.

And now that we are approaching the completion of this essay, we will move from Augustus to Augustine. In The City of God, he directly addressed this issue of cyclical versus linear time:

This controversy some philosophers have seen no other approved means of solving than by introducing cycles of time, in which there should be a constant renewal and repetition of the order of nature; and they have therefore asserted that these cycles will ceaselessly recur.

Augustine rejected such notions, which he ascribed to the ignorance of philosophers who could not “penetrate the inscrutable wisdom of God”:

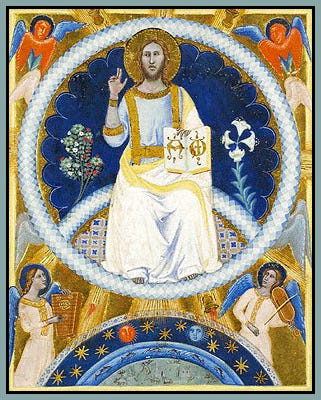

For, though Himself eternal, and without beginning, yet [God] caused time to have a beginning…. And man, whom He had never made before, He willed to make in time.

Furthermore,

Once Christ died for our sins; and, rising from the dead, He dies no more.

For Augustine, cyclical time was a theological impossibility. He saw the fundamental temporal mode of salvation history and of Christian civilization as “linear movement from Creation to Apocalypse, a teleological process directed toward the single goal of individual salvation.”1

We started with linear, teleological time as the prevailing temporal mode of modern thought, then we traveled back to the cyclical time of Antiquity, and now we’ve returned to linear, teleological time—but we’re nowhere near modernity! Rather, we’re looking with St. Augustine at the dawn of the Middle Ages. Given that Augustine and modern culture are about as compatible as fire and water, we need to get this situation sorted out.

We’ll do that in the next post, when we explore the via media: not cyclical time, not linear time, but medieval time.

Andrew Fichter, Poets Historical: Dynastic Epic in the Renaissance. Yale University Press (1982), p. 64

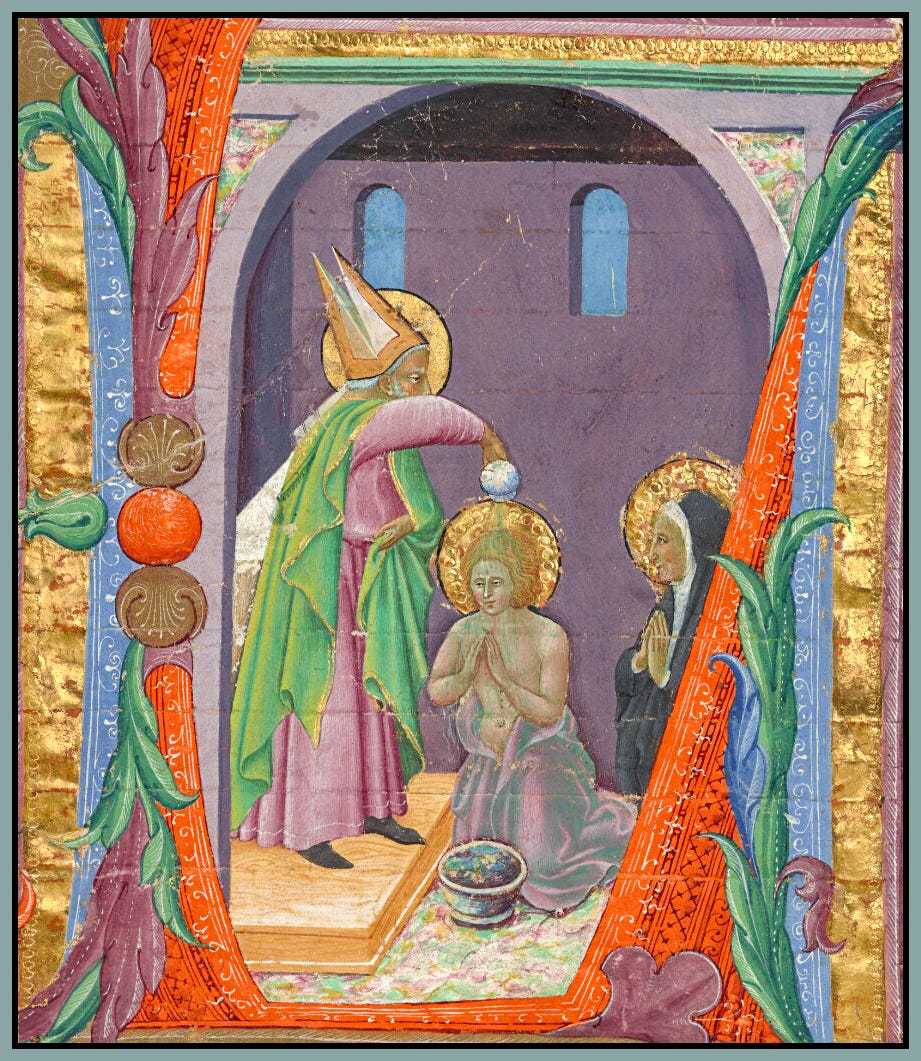

One of the things I hope to experience in my own life, perhaps for a significant portion of the latter part of it, is monastic time. I envy the monks this aspect of their lives perhaps more than any other thing.

You introduce ideas that I never would have considered! Thanks!