Savonarola

One apocalyptic monk, two monumental eras, three dead bodies, hanged and then burned

Imagine that you’re in Florence, “first city of the Renaissance,” in the year 1497. The world still feels rather medieval at times, especially in the countryside, but for a lifelong Florentine like you, (early) modernity is thriving. People are more likely to believe things that their ancestors never believed, and to do what they want rather than what they’ve heard in sermons. The pursuit and enjoyment of material wealth, increasingly allied with the entrepreneurial spirit, is more socially acceptable now, with even priests and religious thinking too much about finances and not enough about Him who “poured out the changers’ money, and overthrew their tables.” Pagan styles are in, with private palaces and public buildings and even churches looking more classical, and less Christian. Artists have imitated and then surpassed the ancients in reproducing the anatomical details, and the erotic energy, of the unclothed human body. And authors are more inclined to explore profane subjects, taking inspiration from the literary forms of Antiquity, and to write not in Latin but in the vernacular. The times, as Bob Dylan observed, they are a-changin’.

Presumably you’re not the type who’s intoxicated with all these new ideas, and you’re not sure what to say to your kids about all the half-naked Greek gods in town, and of course you’re not pleased with the way the young ladies are dressing these days, but still—you’re used to it. Petrarch, your fellow Tuscan whose poetry and scholarship laid the foundation for post-medieval “humanism,” died over a century ago. For you, Renaissance Florence is simply Florence, a place where life is more monetary, religion a little more worldly, culture much more zesty, and premarital pregnancy rather more common, than it used to be.

It’s early February. You need to visit some old friends, and your route takes you through the political center of the city. As you approach the Piazza della Signoria from the west, something catches your eye. Curiosity adds a spring to your step, and though you’ve grown accustomed to strange novelties in these heady days of the Italian Renaissance, you really don’t know what to make of this one. Soon you’re close enough to confirm that it is, indeed, a massive wooden pyramid. You stop, and wonder, and stare—right about here:

It’s sixty feet tall and has eight sides, and each side has fifteen shelves. The shelves are not empty. No, in fact, they’re filled. But with what?

Having learned a bit of medieval superstition from your grandmother, you hesitate to come too close. Aren’t pyramids a symbol of the devil, or of heathen idols, or some such? The other folks milling around seem fine, though, so you venture in a few steps, then a few more, and gradually you discern the astonishing variety of objects with which those great wooden shelves are laden:

shameful pictures and sculptures, gambling devices, musical instruments and music books, masks, costly foreign draperies overpainted with immodest scenes, sculptures of very beautiful and shapely ancient Roman and Florentine women by Donatello and other great masters, gaming boards, playing cards, dice, harps, lutes, zithers, harpsichords, dulcimers, pipes, cymbals, … hairpieces, diadems, cosmetic cases, polish, mirrors, perfumes, face powder, musk, wigs[, and] … “all the lascivious Latin and vernacular books,” including not only Luigi Pulci’s Morgante but also Petrarch, Dante, Boccaccio’s Decameron.1

(In other words, “every diabolic instrument then in use,” to borrow a phrase from a contemporary writer.)

It’s a dazzling sight, to be sure. More than a few of those items would make a fine addition to your parlor decor or your bookshelf, but nobody seems to be buying anything. Actually, you’ll later hear that a Venetian merchant offered to purchase the pyramid, with all its “diabolic” cargo, for 20,000 ducats (well over a million dollars in today’s money). It wasn’t for sale.

The sound of psalms, chanted by youthful voices, draws your attention away from the pyramid and toward the northern entrance to the piazza. It’s a procession, arriving with full ceremonial from the Cathedral, where lauds in honor of the Virgin has been sung. A glorious sight it most surely is, complete with silk canopy and red crosses and a statue of the Christ Child borne aloft on the shoulders of His faithful servants. But as the procession files into the square, with the participants taking up their positions on either side, something feels not quite right. You even have a vague sensation that they’re arrayed for some kind of battle. They begin to sing again, but the song has changed—it’s a hymn not of praise, but of condemnation. Now thoroughly unsettled, and not at all keen to get embroiled in a political controversy, you decide it’s time to move along. But you haven’t got far when you notice the unmistakable aroma of woodsmoke in the air: a dark cloud rises above the rooftops of Florence, and fiery tongues climb inexorably up the doomed edifice. Soon the pyramid is a towering pillar of raging flames, which warm your face as you behold a spectacle at once so captivating and so terrible.

It is the Bonfire of the Vanities, and its author is a Dominican friar—and a saint? or a madman?—by the name of Girolamo Savonarola.

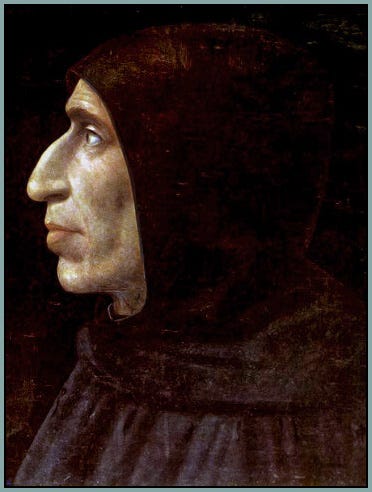

Our topic last week was the Renaissance: whether it existed, what it was, and how its relationship with the ancient world differed from that of the Middle Ages. But I like to put a human face on things when possible, and for me, the face that most dramatically conveys the vexed transition from medieval to Renaissance culture is the one you see above. It belongs to a man who conquered Florence with little more than his erudition, his preaching, and his apostolic zeal, and who died right around this time—May 23rd, to be precise—in the year 1498.

A quick online search will bring up plenty of biographical articles on Savonarola, and you might also find some discussions on what exactly he was: Reformist heretic or Catholic hero? Ambitious visionary or delusional fanatic? I don’t want to spend much time on information that is widely available elsewhere, and I certainly won’t pretend to unravel the mystery of a life that is and will always be fundamentally mysterious. I will say, however, that I instinctively distrust people who publicly claim to have received private communications from Almighty God, and Savonarola did precisely that. Pope Alexander VI apparently had similar misgivings, and he suggested that Savonarola come on over to Rome and explain himself. The fiery friar declined, and things went downhill from there.

What I’m more concerned with in this week’s articles is Savonarola’s status as a liminal figure: that is, as someone whose interior life seems to have been an unstable compound of medieval and Renaissance culture, and whose death—whose violent dissolution, we might even say—seems to confirm how deeply inharmonious those two cultures were.

His biography is definitely worth reading, though. There weren’t many in fifteenth-century Italy with a story like his: he began his adult life as an ordinary Catholic monk, gained recognition as a preacher, wrote some unremarkable philosophy textbooks, attracted the attention of scholars and a few prelates, inveighed against the clergy (for their greed) and the secular princes (for their immorality) and the judges (for their corruption) and the people (for their degeneracy), developed a knack for apocalyptic oratory, opposed the humanists, proclaimed himself a divinely inspired prophet, preached impending doom and the need for radical moral reform, declared Florence the New Jerusalem and refashioned it into a theocracy subject to his dictatorial rule, won the hearts of the citizenry, convinced most of them to do penance and return to the Gospel, defied the pope who then forbade him from preaching, kept preaching anyway until he was excommunicated, ignored the excommunication (which he deemed invalid), decided that the current pope was not even a Christian and therefore illegitimate, and called for a council that could elect a new pope.

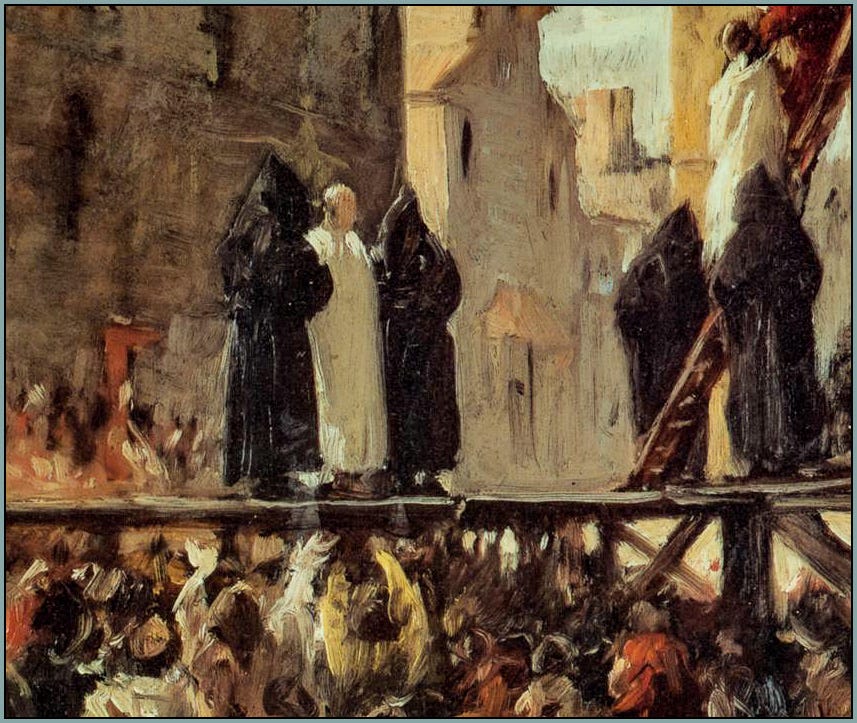

By this point the patience of the authorities, and to some extent of the general populace, was wearing thin. A tragic hero in the epic drama of his own life, Savonarola was in the fifth act, and the story can end in only one way. He was arrested, accused of heresy and schism, tortured, and executed.

On Tuesday we’ll take a deeper look at Savonarola’s status as a complex hybrid of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. And I use that term “hybrid” advisedly: plants and animals that have genetically disparate parentage benefit from “hybrid vigor” (the technical term is “heterosis”). Hybrid varieties can outperform their parent varieties in certain ways, but as many gardeners know, hybrids are also unstable: you can’t save seeds from hybrid vegetable plants because they don’t reliably pass their traits to their offspring. When I look at the profound fervor and extraordinary accomplishments of Savonarola’s life, I see an exceptional spiritual vigor born of the union between medieval and Renaissance Christianity, and when I look at his extremist tendencies and catastrophic demise, I see this vigor ending in doctrinal disorder and spiritual sterility—much as post-medieval European culture suffered increasingly from doctrinal disorder and spiritual sterility.

To conclude this essay, then, let us return to the place where we began: the Piazza della Signoria. This time it is not the great wooden pyramid that looks down upon the populace, but three motionless human beings: Savonarola and two of his followers have been hanged. Nor is it the “vanities” of Florence that will be consumed by flames: the bodies of these executed—martyred?—Christians will burn, and the order has been given that the ashes be cast into the river, lest anything remain that might become a relic.

The man who converted Florence is dead.

Many who came to witness the execution … hoped for a sign that would prove the truth of Savonarola’s glorious prophecies. But no sign was forthcoming; he went to his death without a word and their remaining faith was shattered.2

Shattered indeed. For me, that is the essence of Savonarola’s downfall. Was he a believer? Certainly. An eloquent preacher? Undoubtedly. A devoted reformer? Yes. A man who sought to boldly and radically live the Gospel, and who expected others, including the pope, to do the same? It appears that he was. But he strayed too far from the wisdom of medieval saints, of medieval culture more generally, and the harmful effects became cumulative. Increasingly, he lacked wholeness, balance, stability, interior harmony. He internalized the stress fractures and incongruities of the world around him, and eventually, the life resulting from all this—a fragmented life, lived by a fragmented self—was shattered.

Donald Weinstein, Savonarola. Yale University Press (2011), p. 218.

Ibid., p. 1.

Alexander VI? Heaven help us. History is written by the rich and powerful. No matter that it is as full of holes as a rusty colander. My sense of Faith tells me this saintly Dominican held the Truth, and was martyred for it.

One of the first “celebrity priests” gone bad… it seems like extremism in religion must be born of too much self-love, of thinking you have God’s ear to yourself. A sad tale.