Twice or thrice had I lov’d thee,

Before I knew thy face or name;

So in a voice, so in a shapeless flame

Angels affect us oft, and worshipp’d be;

Still when, to where thou wert, I came,

Some lovely glorious nothing I did see.

—John Donne

If I had to choose one medieval artifact that most eloquently expresses the importance of angels in medieval culture, it would be this:

How strange it is to think that men once built such things as Mont-Saint-Michel, instead of this:

What words might we use for this monument to the medieval world’s most beloved and illustrious angel? Magnificent, breathtaking, awe-inspiring? They feel inadequate—perhaps because these adjectives often describe things that belong primarily to the earth, and for people like us, living as we do in an age of enormous human filing cabinets (what some people call skyscrapers) and curiously designed stationary suburban spaceships (confusingly identified by their signage as churches), Mont-Saint-Michel seems to have come more from heaven than from earth. To suggest that it was envisioned and built—over the course of many centuries, by the way—solely by human beings is thoroughly implausible. The more likely scenario, surely, is that the place is named for St. Michael precisely because it was the archangel himself who drew up the plans and superintended the construction. The available records do not indicate how many of his laborers were of celestial origin and how many of terrestrial, but the collaboration was clearly a fruitful one—for there is quite simply nothing upon this earth that entrances the eye and thrills the imagination in the way that Mont-Saint-Michel does.

For those who incline to a more scientific temperament, as I once did, and who therefore doubt that St. Michael built his own castle on a tidal island in northern France, as I (alas) still do, allow me to insist that the idea is undeniably factual, if understood more broadly. For even if Mont-Saint-Michel is exclusively the work of human hands, these hands were animated by souls that not only believed in angels, not only celebrated their feasts and invoked their aid, not only saw them in books and paintings and stained-glass windows, but felt their presence with a ubiquity and intensity and deep affectivity that are virtually unknown and almost unimaginable in the modern world. These were people who saw in the earth a poetic, symbolic wonderland that though ravaged by sin and weighed down with suffering was nonetheless a many-melodied song that ever and always sings of heaven. These were Christians who lived in and inherited the incarnational spirituality, keen intellectuality, and enchanting cosmology of medieval Europe. These were men, women, and children—like you, like me—who lived in the Age of Angels.

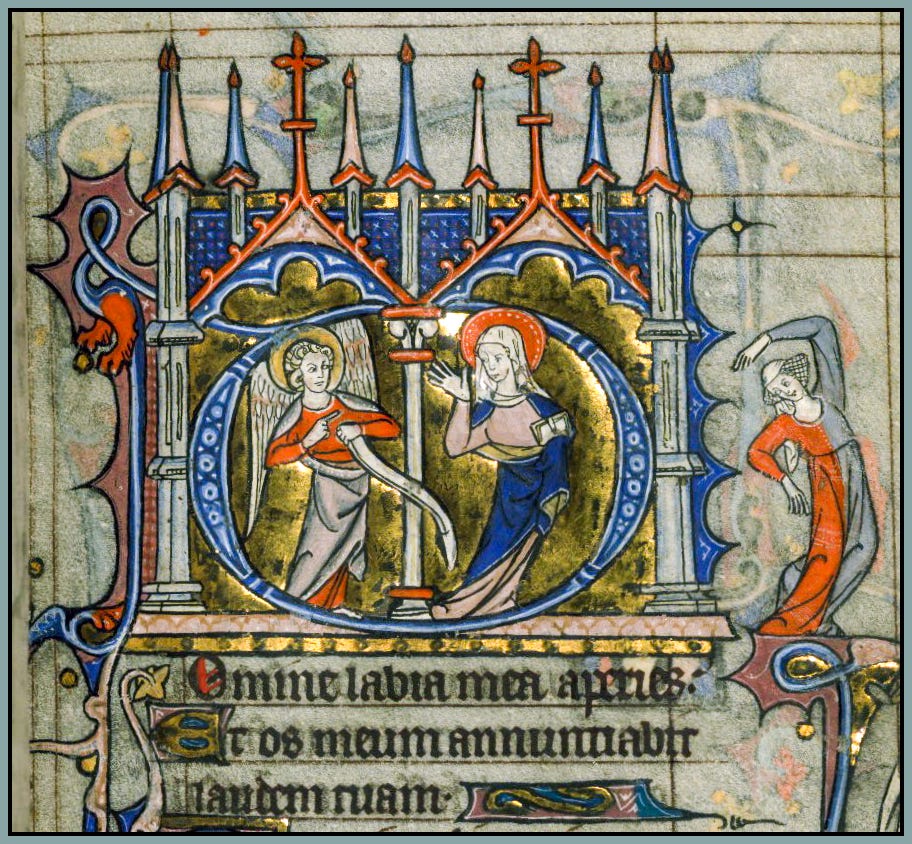

A Google image search for “St. Michael” yields a dizzying crop of pictures in which a militaristic angel is decked out in plate armor, perhaps with duly bulging muscles accentuated by dramatic lighting. These are generally not to my taste. Though I of course have nothing to say against the long and venerable tradition of anthropomorphism in Christian art, such things have their limits. The captain of the heavenly army does not need elaborate weaponry or substance-enhanced musculature to vanquish his enemies—he fights with the strength of Almighty God against spirits whose tragic downfall has reduced them to feckless beasts, as depicted in the illumination above, where St. Michael makes war with the pose of a dancer and wears an elegant robe instead of hammered steel. And did you notice the expression of his face?

He is relaxed and serene, displaying the “tranquility of order”—to borrow a phrase from St. Augustine—and even imposing order on the unruly demons that foolishly oppose him. Furthermore, he is enjoying himself. There is pleasure in fighting the good fight, pleasure in dispensing the immaculate justice of God, pleasure in a battle that moves inexorably toward victory.

It just so happens that this illustration dates to the middle of the thirteenth century, which the historian Dr. David Keck, an expert in these matters, identified as “the most important of all medieval centuries for angels.” The image says a great deal, if we listen carefully, about the simple, sturdy piers that supported the vast and intricate edifice of medieval angelology. The angels are beautiful; the demons are not. The angels are above; the demons are below. The angels resemble humans; the demons do not. The angels are clad in blue, the color of the heavens, and green, the color of life; the demons are red, the color of the infernal fires. And despite the violence and turbulence that surround them, perhaps endanger them, the angels are peaceful, even cheerful; the demons, in contrast, are ill-humored, embittered, (literally) twisted: disordered. This is crucial: medieval societies—with their love and admiration for order, cyclicality, balance, music—were naturally and powerfully drawn to the glorious harmonies, graceful movements, and hierarchical order of the angelic host.

Also, angels were inherently mysterious. Their presence and prominence in the Bible were indisputable, and yet, the sacred authors give no explanation of what exactly an angel is. How, for example, can a bodiless spirit “guard the way of the tree of life”? The Hebrew word (malak) means messenger; Greek angelos means messenger; Latin angelus is merely a borrowing from the Greek. Angels in medieval Christianity were perceived as much more than divine messengers, and even to assert that an angel is a messenger is rather tautological: “an angel is a messenger” means “a messenger (angelos) is a messenger.” The scholars of the later Middle Ages delighted in this mystery. They philosophized and theologized tirelessly about metaphysical questions that were intertwined with the nature of angelic existence—questions on which Scripture was practically silent, and to which the Church Fathers offered answers that did not satisfy the extraordinarily active minds of medieval society’s educated classes.

There was yet another facet of the angelic host that appealed to medieval thought and helped the angels to weave themselves so freely and thoroughly into the fabric of medieval life. Angels, like the culture of the Middle Ages, are deeply paradoxical: they dwell in the luminous heavens and sing everlasting praises to the everlasting God, but they also seem very much involved in, responsible for, even sincerely interested in the humble happenings of earth. How can any created being pass so freely between the realms of time and eternity, perfection and corruption, bliss and sorrow?

We had a brief glimpse into the extraordinary richness of medieval angelology last week, in the conclusion to my series on symbolism. Indeed, the angelic host seems to have a special association with the symbolic energies that circulate through the material universe. I will remind you of the quote from Cardinal Newman, who lived a great temporal distance from the medieval world yet certainly knew something of its spirit: “Every breath of air and ray of light and heat, every beautiful prospect, is, as it were, the skirts of [the angels’] garments, the waving of the robes of those whose faces see God.”

As you may have guessed by now, we are transitioning from an extended discussion of medieval symbolism to an extended discussion of medieval angels; the two topics are, as we will see, more closely related than one might think. I hope that the essays to come will give you the opportunity to see these mysterious, benevolent, heavenly beings in a new and glowing and jewel-toned light—in the light, that is, of the Middle Ages.

I think the use of your voice came out well. I appreciated the audio.

Thank you for the audio! Great article too.