This is the concluding essay in a series on the transformative role of symbolism in medieval life and in our lives. The preceding articles are listed below.

“Alack,” says Shakespeare’s Juliet, “alack, that heaven should practice stratagems / Upon so soft a subject as myself.” By a strange path indeed have I come to where I am, and to look back is only to wonder at the mysterious workings of Providence.

The place was a high school English class; my age was seventeen. The teacher, a man of curious propensities, showed us a portion of a video that appealed to him for some reason. I don’t remember why we were watching it, what it was called, what its primary subject matter was…. I actually remember almost nothing about it except for a short scene that has, against all odds, remained quite clearly in my memory from that day to this.

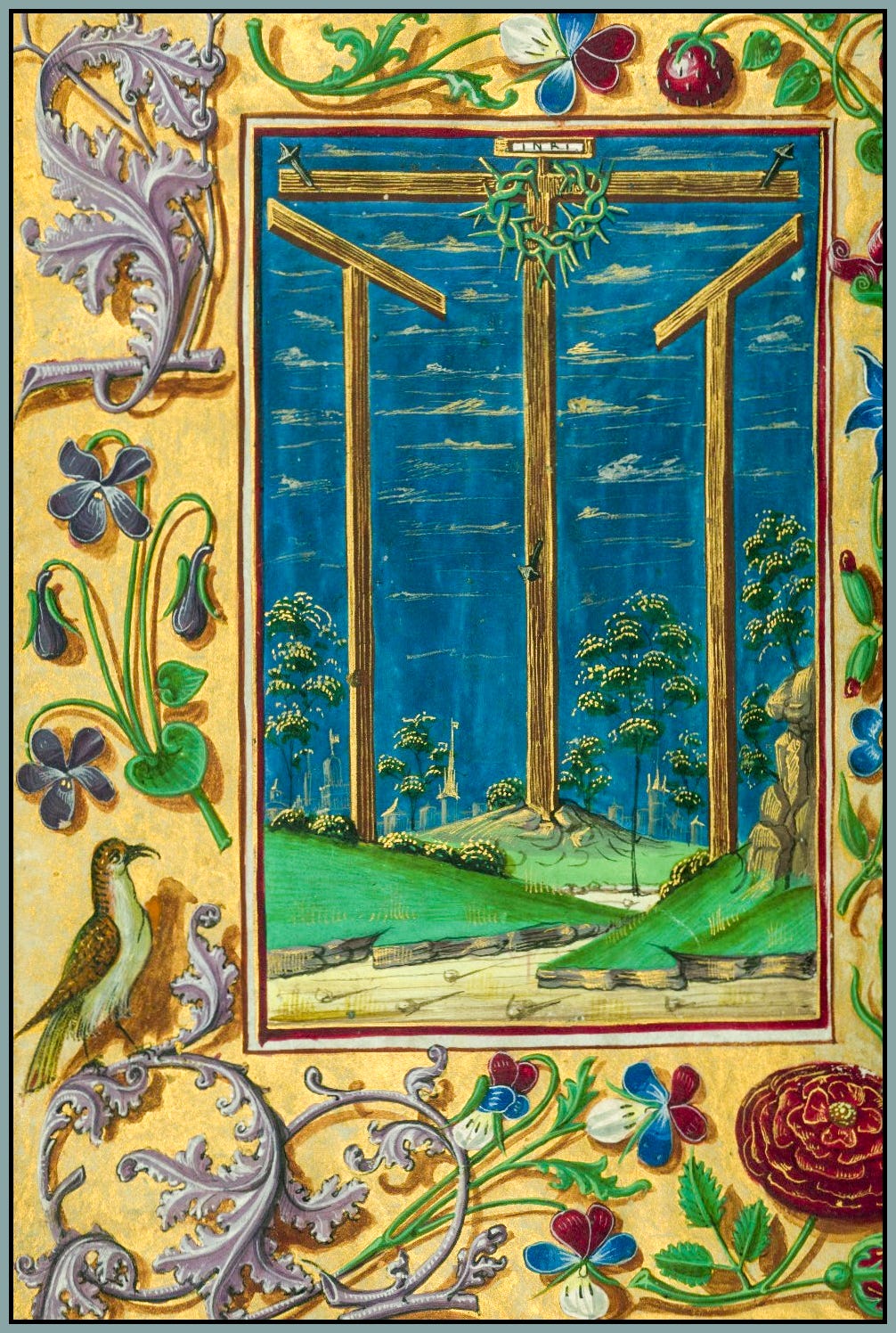

An older man with a British accent—some sort of scholar, I think he was—knelt down next to a rose plant and looked at the camera. He was talking about the Dark Ages. Don’t quote me; the words have faded and I’ll need to fill in the gaps. But he was saying something about the modes of thought in medieval—i.e., “illiberal, barbarous”—culture. You see, people back then knew basically nothing about science. Those poor medievals looked at rose plants and had no idea that their red flowers were red because they reflected long-wavelength light, or that their white flowers were white because they reflected all wavelengths of light, or that their stems had thorns because thorns are an evolutionary adaptation. Instead, medieval people—pitifully ignorant but good pious folk they were—medieval people looked at rose plants and said that they have red flowers for the Blood of Christ, and white flowers for the purity of the Virgin Mary, and thorns for the Crown of Thorns.

At that time in my life, the Middle Ages seemed about as relevant to my destiny as an uninhabited island somewhere in the Arctic Circle. So I really had no strong reaction to what I was watching. I suppose it struck me as mildly charming in a preposterous sort of way. Or if it wasn’t charming, it was certainly preposterous. I had already learned more than enough science to understand how hopelessly lost those medieval peasants must have been if they looked at a rose plant and saw a green, growing mirror of religious beliefs.

Oh, the twists and turns of fate! I was seventeen, the future was bright, and the video was quickly forgotten—or so I would have thought. Somehow it stayed with me, and I was able to remember it many years later when I finally realized that I was wrong about roses, and that those medieval peasants were right.

“Why is the sky blue?” It’s a question that children ask. Let’s pose it to Google and see what the AI bot gives us: “The sky is blue because of a process called Rayleigh scattering, which occurs when sunlight passes through Earth’s atmosphere and is scattered by air molecules.” Well done, Google—that’s a correct answer.

Well, not quite. The statement is correct, but as far as I’m concerned, it’s an answer to a different question. When Google says this, and when all the humans whose knowledge Google has consumed say this, they are explaining how the sky is blue. They’re describing a physical process by which the white light from the sun is converted into blue light that reaches our eyes when we look up toward the heavens.

I would like an answer to the question I asked: Why is the sky blue? What is the reason, the purpose, behind this blue sky? That’s not the sort of question Google understands, though. We’ll have to look elsewhere.

For those who believe that God exists and that He created the universe with love and wisdom, there can—in my view—be only one answer. If God created the universe with intention and diligence and foresight and good will toward its eventual inhabitants, the only answer is this: the sky is blue because a blue sky symbolizes something more important—more eternal, more enlightening, more spiritually liberating—than a blue sky.

An eminent medieval scholar named Hugh of St. Victor (d. 1141) thought a great deal about symbolism. He said this:

The whole world is open to our senses as if it were a book written by the finger of God, … and everything created is as it were a symbol, not invented by human whims, but ordained by the will of God, to make manifest and, as it were, to signify in some way the invisible wisdom of God.

“Everything created is … a symbol … ordained by the will of God … to signify in some way the invisible wisdom of God.” That’s a monumentally consequential statement, and it was not Hugh’s innovation. Rather, he was elaborating upon a tradition inherited from the ninth-century theologian John Scotus Erigena:

God realizes Himself in the creation, manifesting Himself in wondrous and ineffable manner; though invisible, He becomes visible, and though incomprehensible, He becomes comprehensible.

And from Origen, the illustrious theologian of the early Church:

All things in the visible category can be related to the invisible …; the creation of the world itself … can be understood through the divine wisdom, which … teaches us things unseen by means of those that are seen, and carries us over from earthly things to heavenly things.

And from the Psalmist:

The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament showeth the work of his hands.

And from Plato, who imagined men chained up in an allegorical cave—men who could not see the real objects moving through their world, but instead saw only the shadows of these objects. For men such as these,

the truth would be nothing but the shadows.

Plato was right, except that the shadows of which he speaks were made by God, and they are good, and beautiful, and true. But if we wish to be fully alive, we must nonetheless recognize that they are, in a certain sense, shadows, and that the realities which they signify are more good, and more beautiful, and more true.

Plato has led us to the crux of the matter. Our preceding study of medieval symbolism in numbers, primordial elements, flowers, and churches has already indicated that all of Creation is a vast, particolored, multifaceted masterpiece of physical realities that signify the higher things of the mind and spirit. The quotations above, from great thinkers of the Christian and pre-Christian past, confirm this notion. But we need to go one step further to reach our destination in this journey to the heart of the symbolic life. We need to follow Hugh of St. Victor’s theology to its logical conclusion:

The material universe is filled with objects that declare the presence of poetic and emotional and spiritual and heavenly things, and furthermore, these objects, like the shadows in Plato’s cave, are not the truest reality. They are not objects that happen to be symbolic. They are symbols first, and objects second.

I am convinced that it cannot be any other way, for when the Almighty was in the midst of creating the world, what was foremost in His Mind? The material object, which will perish someday, or the symbolized Truth, which is eternal and incorruptible? The plants and animals, which will die someday, or the angels and saints, who live forever? That which is noble and spiritual and cosmic and salvific must take precedence over that which is ordinary and carnal and ecological and utilitarian. The symbolism must take precedence!

What would be the thoughts of a man who, when examining a flower, or a herb, or a pebble, or a ray of light, … suddenly discovered that he was in the presence of some powerful being who was hidden behind the visible things he was inspecting, … [and] whose robe and ornaments those objects were?

—St. John Henry Newman

Let us gaze with wonder, then, upon the awe-inspiring glory of Creation; let us marvel at the overpowering goodness of the Creator: sun and moon, trees and flowers, silver and gold, bird and beast, food and drink, flute and harp, home and hearth, summer and winter, wind and rain, fire and ice, land and sea, meadow and mountain—they all are voices that sing to us of God! They all exist first and foremost to declare the presence of higher things. They are deeply known, truly seen, fully enjoyed only when known, seen, enjoyed as symbols.

Roses have thorns because there was once a Crown of Thorns. They have white flowers because the Virgin was pure. They have red flowers because Christ shed His Blood for our salvation.

How is the sky blue? Raleigh scattering.

Why is the sky blue? Because very few objects on earth are naturally blue, and therefore a blue sky tells us that the divine realm is a sacred mystery, and that the joys of heaven far surpass those of earth, and that the thoughts of the Deity are not our thoughts.

How is the sun a luminous, flaming orb? Nuclear fusion.

Why is the sun a luminous, flaming orb? Because the Gospel of Christ is the light of the world, and He burns with prodigious, self-sacrificing love.

How does the moon have phases? Changes in the relative positions of the sun, moon, and earth.

Why does the moon have phases? To symbolize the enduring love and providence of the heavenly Father, who is always with us, even when He seems absent—as the Psalmist says, “established forever like the moon, a faithful witness in the sky.”

How does a guitar—a wooden cavity with a few stretched strings—produce such sonorous, enchanting sounds? Sinusoidal vibrations of air molecules.

Why does a guitar produce such sonorous, enchanting sounds? My guess is because the good God wanted us to know what an angel’s voice would sound like if we could hear it. Saint John Henry Newman said of the angels, “Every breath of air and ray of light and heat, every beautiful prospect, is, as it were, the skirts of their garments, the waving of the robes of those whose faces see God.”

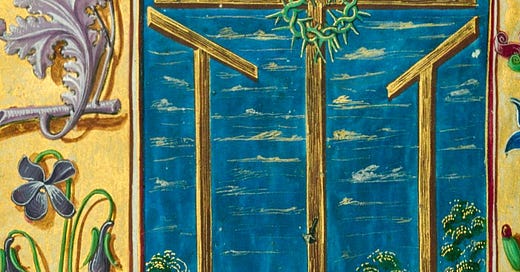

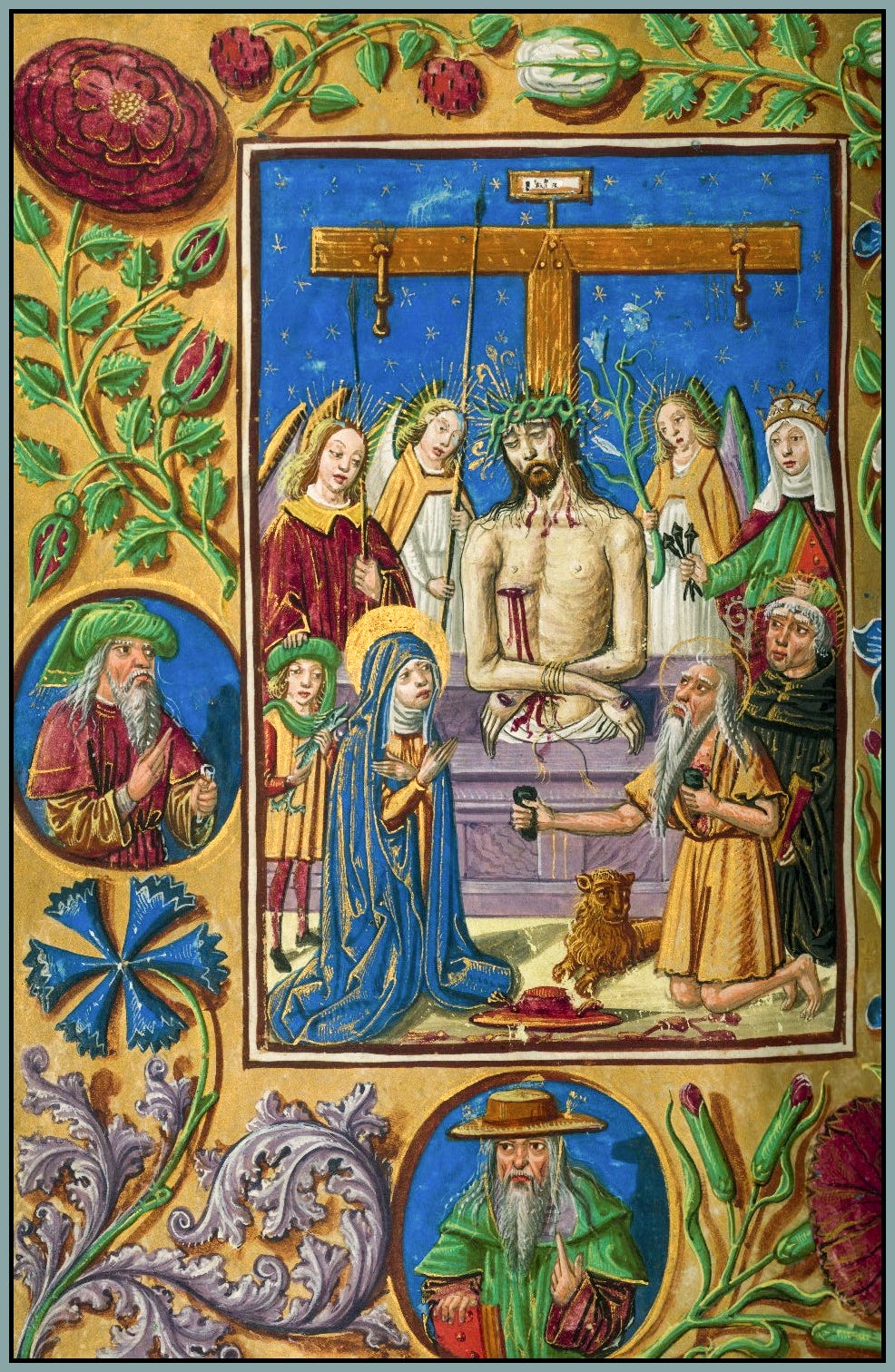

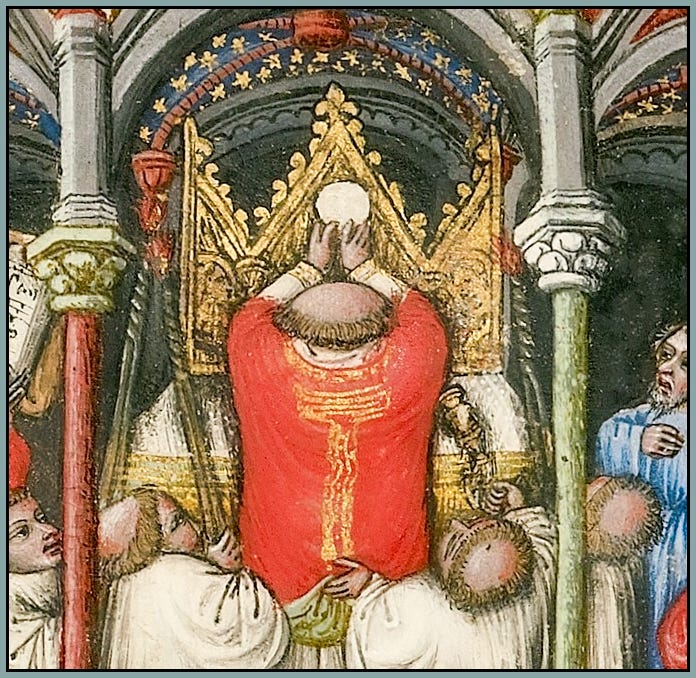

Why is bread so vibrant and beautiful when growing as a plant, and so rich and golden when cut down in death, and so nourishing when eaten as food, and so readily broken and shared with friends? I will answer that one with a picture instead of words:

There is no feast without symbol. There is no complete celebration, no true fellowship, no fullness of joy if we do not recognize that the things we perceive with our senses are, and were intentionally created to be, so much more than sight, sound, aroma, taste, and touch.

Let the drab, prosaic pragmatism and cynical, suffocating materialism of modernity fade away into the nightmares of history, to be replaced by this waking dream, this cosmic poem, this living icon, this tapestry by angels wrought, this wondrously symbolic world that will surround us every moment of every day until our eyes are closed in death—and then opened unto many Truths of which the signs and symbols spoke.

Everywhere we look, the universe is radiant with meanings that illuminate divine truths, and signify the ineffable goodness of God, and lead us to our true destiny. Let our minds ponder it, let our eyes delight in it, let our hearts draw warmth from it, let our weary, wounded, starving modern souls make feast and festival within it. This is the day which the Lord hath made; let us rejoice and be glad in it.

Why is the sky blue? On reason is to remind us that our Blessed Lady has her mantle spread over us in loving protection. At least it reminds me and hopefully now whoever reads this.

Rephrasing the question as you have done, turns the whole world inside out. It’s so liberating to feel the creative soul within nature as opposed to staring outwards barred from the world’s life by heady misconceptions. My eyes will feast on blue today. Gracias.