The Huns were on the move, heading west. Scholars still don’t know who exactly they were. Their ethnic origins and racial characteristics are not well understood, and little of their language has survived. They emerged from somewhere in Inner Asia and lived a nomadic, pastoral life on the steppe—a hard life it surely was, and it made them a hard people. They fought on horseback, with the bow and the sword, and were a force to be reckoned with. Even the fabled soldiers of Rome were impressed with their discipline on the field of battle. The Strategicon of Maurice, a Late Roman military treatise, recommended attacking them in late winter, when their horses were weak. That seems like good advice, but it doesn’t help much if they decide to attack you in June, when the meadows are lush, and the horses strong.

The northern coast of the Black Sea led them from Asia into eastern Europe, and around the middle of the fifth century AD, they were in central Europe. At this point they were not so loosely organized as before—their society had become more hierarchical, and at the top of that hierarchy was a Hun named Attila. It’s hard to know what to make of him. Attila wasn’t the proverbial “nice guy” so often mentioned with approbation in modern conversations—he broke treaties, laid waste to cities and regions, murdered his elder brother, and so forth. But the kings and warriors of medieval Christendom weren’t nice guys either, and Attila must have been a remarkably skilled leader to accomplish all that he did. Skilled leadership is in short supply, these days. Also, it’s hard not to admire the self-aggrandizing audacity of a man who claims the sister of a Roman emperor as his wife and then suggests that he be given, as a dowry, half of that emperor’s empire.

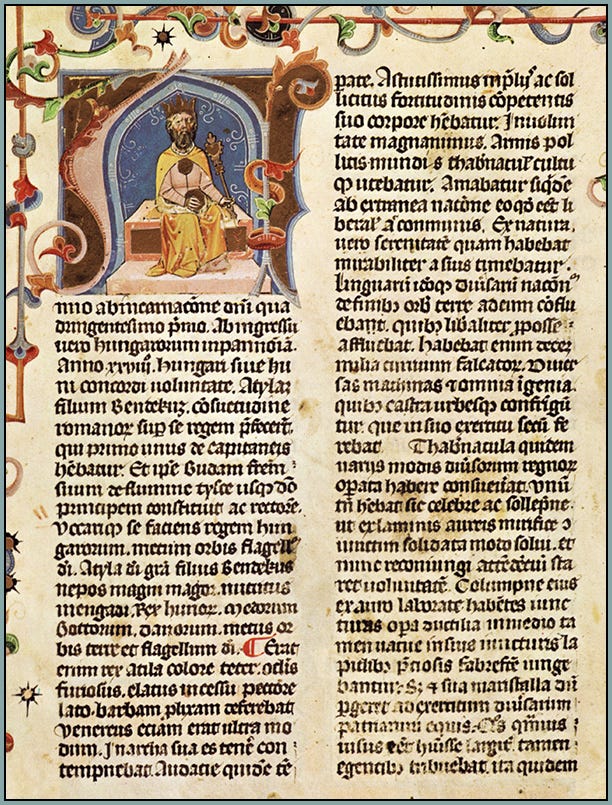

Even in the minds of medieval Christians, who were much closer in time and space to Attila’s rampaging exploits than I am, there’s an interesting ambivalence surrounding this most famous king of the Huns: the barbarian general who threatened the city of Rome is also “the Dread of the World” and “the Scourge of God.” Those appellations are found in the Chronicon Pictum, an important fourteenth-century codex also known as the Chronica de Gestis Hungarorum: “Chronicle of the Deeds of the Hungarians.” Here is the passage in question:

The Latin word metus is not purely negative: it’s “fear, anxiety” but with a touch of “awe.” And what are we to make of flagellum Dei? Attila was a scourge, to be sure, but the scourge of God? Medieval Christians, accustomed to viewing reality through the lens of Sacred Scripture, understood that the Almighty could somehow use a pagan warlord as an instrument in dealing with the sins of His own people. They understood, furthermore, that the real scourge, always and everywhere, is sin. Even when the problem appears to be Attila or the Vikings or bubonic plague (or climate change), the real cause—the fundamental cause—of our woes and miseries is always sin.

To make a long story short, Attila invaded Gaul in 451 and was defeated. As a consolation prize he went to northern Italy and wreaked havoc, burning and killing and destroying his way toward Rome. But before he got there, a man went out to meet him. This man had no weapons and no army, but his name was Lion, and he believed in God.

What exactly Pope Leo the Great said to Attila will never be known. The following contemporary account, from a theologian and saint named Prosper of Aquitaine, gives no details:

To the emperor and the senate and the Roman people, none of all the proposed plans to oppose the enemy seemed so practicable as to send legates to the most savage king [i.e., Attila] and beg for peace. Our most blessed Pope Leo—trusting in the help of God, who never fails the righteous in their trials—undertook the task…. The outcome was what his faith had foreseen, for when the king had received the embassy, he was so impressed by the presence of the high priest that he ordered his army to give up warfare, and after he had promised peace, he departed beyond the Danube.

I like how Leo is identified as “the high priest.” Maybe if this title were applied to modern popes from time to time, the office would feel a little more sacerdotal, and a little less political.

This account was later expanded and dramatized by an anonymous writer. In the second version, Leo—an “old man of harmless simplicity, venerable in his gray hair and his majestic garb”—addresses Attila as “king of kings,” speaks to him about the glory he has already attained in subduing the Romans, and then asks for clemency: “The people of Rome, once conquerors of the world, now indeed vanquished, come before you as suppliants…. We pray that you, who have conquered others, should conquer yourself. The people have felt your scourge; now as suppliants they would feel your mercy.” The words sound to me like the author’s rhetorically embellished attempt to convey the assumed content of Leo’s message. I find them rather distasteful, and the miraculous intervention, completely absent from St. Prosper’s description of the encounter, doesn’t appeal to me either:

As Leo said these things, Attila stood looking upon his venerable attire and aspect, silent, as if thinking deeply. And lo, suddenly there were seen the apostles Peter and Paul, clad like bishops, standing by Leo, the one on the right hand, the other on the left. They held swords stretched out over his head, and threatened Attila with death if he did not obey the pope’s command. As a result of this, Attila … promised a lasting peace and withdrew beyond the Danube.

I am much more inclined to believe that Pope Leo’s “victory” over Attila the Hun was the work of a wise and holy man assisted by a more subtle sort of miracle: “When they deliver you up, be not anxious how or what ye shall speak: for it shall be given you in that hour what ye shall speak. For it is not ye that speak, but the Spirit of your Father that speaketh in you.”

However, we should keep in mind that medieval writers didn’t necessarily intend for such prodigies to be interpreted as historical fact. Indeed, I think that an allegorical interpretation is reasonable here: Peter represents the power of Leo’s papal office, and Paul represents the power of his words. Both are “clad like bishops” and “standing by Leo,” because they convey two complementary aspects of what the bishop of Rome is doing. Attila, though a pagan man, was not a modern man, and therefore he would have known a thing or two about fearing the gods. The outstretched swords thus represent Attila’s awareness that there is something divine, and therefore dangerous, in Leo’s priestly mien and grave words—perhaps the king’s reaction was akin to that of the guards sent to apprehend Christ: “Never did man speak like this man.”

I don’t think that Leo described Rome as vanquished and then begged Attila for mercy. In my imagined version of the encounter, Leo knows that it is actually Attila, a worldly chieftain and a man of blood, whose downfall is assured, whereas Rome is rising toward new glory built not on the strength of its legions but on the truth of its doctrine, the beauty of its liturgy, and the holiness of its Christian heroes—and notice how Leo embodies all three of those things: he was the pope, that is, the defender of Truth and the guardian of Tradition; he was a priest, that is, a sacred minister who celebrated the Roman Church’s ritual sacrifice; and he was a saint.

Attila looked into Leo’s eyes and saw something that frightened him. It wasn’t rage, cunning, hatred, defiance—he was used to all that. What he saw, quite simply, was peace. Not the “peace” that modern churchmen often talk about, and which is more a sound than a word, because it means almost nothing. This was the peace of a man who came out from the city of martyrs, and who carried no weapon, brought no military escort, commanded no soldiers, and would have died right then and there to defend the Faith he had received from his fathers. It was the peace, in other words, of someone who, having stored up his treasure in heaven, sees the false pleasures and fickle plaudits and fleeting dominions of earth for what they really are—vanities.

Attila was the type who could stare down a massive horde of bloodstained, battle-hardened, war-crying enemies, and smile. But remember what St. Prosper wrote: “he was so impressed by the presence of the high priest…” The one thing Attila was not prepared for, the one adversary that made “the Dread of the World” deeply uneasy, was a man whose appearance and words and actions all combined to make one fundamental statement: You, Attila, are nothing; God and His Truth are everything.

He replies, disconcerted but feigning confidence: “Do you not tremble at my armies? Do you not lust after my riches? Do you not know of my conquests?” The Leonine eye, unmoved as the eternal hills, gazes back. “For what shall it profit a man, though he should win the whole world, if he lose his soul?”

You don’t need to be a Christian to fear death, oblivion, utter powerlessness, eternal irrelevance. And even a barbarian can feel the weight of the dark cloud of divine chastisement—looming ever lower, drawing ever nearer—when the person who warns him of it is not an opportunist, or a blasé politician, or an internationally recognized “nice guy,” but a saint, who seeks first the kingdom of God and speaks the truth, in season and out.

As the negotiations were drawing to a close, the Hun seemed somehow smaller than before, the pope somehow larger. But still, the barbarian had his army, his weapons, his health—why not kill the high priest, and then kill his attendants, and then march on Rome, and show everyone that he was still a mighty conqueror, still unsurpassed in the destroying of civilization, the pillaging of culture, the spilling of innocent blood?

The priest, though, had once again that maddening look in his eye. Why is he not afraid? The Hun’s own thoughts were preying upon him now—troubling his mind, weakening his body, smothering his ambition, undermining so much that he thought he knew about his poor, earthbound life. What is this bishop of Rome, and why does he never recoil, never reconsider, never recant? The warrior was in a fragile psychological state when the final blow was struck: “Rome cannot defeat you, Attila, it is true. But those who live by the sword shall die by the sword, and when the battle is over, God will know His own.”

And that was the end of Attila the Hun. He did not attack Rome, nor did he remain in Italy. The following year, he was dead.

Good of you to recall Leo I (and in a splendid, grounded imagining). Much of the comment on Leo XIV has relied on describing Leo XIII, and it’s great to see the older namesake in detail.

Love it! Great art accompanying this post too.