The Medieval Art of Living an Epic Life

Facilis descensus Averno...

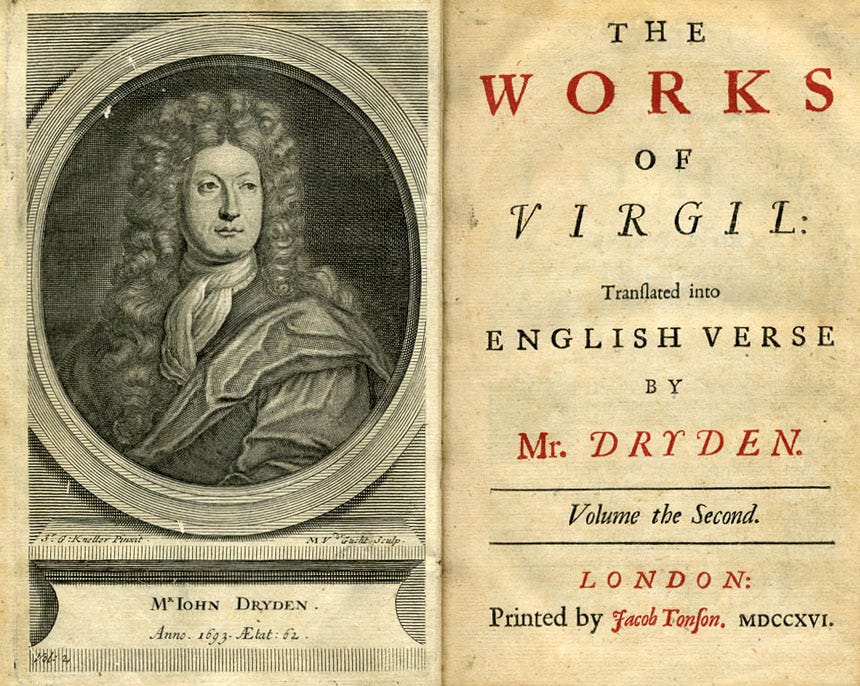

The poet laureate John Dryden published his translation of Virgil’s Aeneid in 1697, about a decade after doing something that respectable English gentlemen of his era almost never did: converting to Roman Catholicism. The release of Dryden’s Aeneid was a landmark event in the history of English letters, and a fairly direct result of his conversion. Stripped of lucrative posts (and his laureateship) in 1688, when he refused to swear allegiance to the invading Protestant Dutchman William of Orange, Dryden became one of those pitiable souls who must make an income from writing poetry. Fortunately, he didn’t starve, and he probably didn’t have to scratch out his verses in an unheated garret by the fading light of a tallow candle. His work on the Aeneid brought in £1400—or about $350,000 in today’s money.

The Aeneid is the foundational epic poem of Western Civilization, and Dryden had some strong words on the value of epic poetry:

An heroic poem, truly such, is undoubtedly the greatest work which the soul of man is capable to perform.

This sentence alone should be enough to make us feel uneasy—how much emphasis does modern education, Christian or otherwise, place on the great epics of the European literary tradition? Not enough. In many cases, not nearly enough.

Dryden’s first justification for thus extolling epic poetry is so simple as to sound almost naïve:

The design of it is to form the mind to heroic virtue by example; it is conveyed in verse, that it may delight, while it instructs.

To delight and instruct, to form readers in virtue, to inspire new heroes—if literature is not doing this, what is it doing? And by the way: as Robert Lazu Kmita recently pointed out, we need saints. The world is dying for want of them. And what is a saint? Someone who has been well instructed in the Truth, and has learned to delight in the Good, and has developed the desire and the ability to practice heroic virtue.

But the roots of Romantic ideology run deep: art is about art, and beauty about beauty—didacticism belongs in the classroom, and preaching belongs in the chancel. “A weak attempt to teach certain doctrines,” says Romantic poet Percy Shelley: “to such purposes poetry cannot be made subservient.” And in any case, observes Romantic poet John Keats, “we hate poetry that has a palpable design upon us.” Furthermore, as the post-Romantic Elizabeth Barrett Browning explains,

We get no good

By being ungenerous, even to a book,

And calculating profits, – so much help

By so much reading. It is rather when

We gloriously forget ourselves and plunge

Soul-forward, headlong, into a book’s profound,

Impassioned for its beauty and salt of truth –

’Tis then we get the right good from a book.

She wrote this in Aurora Leigh—which is considered a Victorian epic. But is she right?

Lately we’ve been studying Beowulf, the only surviving epic poem from early-medieval England, and I wanted to specifically explain what an epic is and what some of its key features are. We’ll continue this topic in Tuesday’s post for paid subscribers, where I’ll give you an example of heroic conventions at work by sharing some poetry I wrote about a uniquely heroic historical figure.

Beowulf is an epic in the broad sense of a long poem that narrates the deeds of a heroic character. With a loose definition like this, we can include various other vernacular works of medieval literature in the epic category: the Song of Roland, the Song of My Cid, the Nibelungenlied, the Alliterative Morte Arthure. Some prefer to define an epic as simply “a long narrative poem,” at which point the genre is so vague as to be of little value and may even include the Roman de Brut (which is a chronicle in verse), Piers Plowman (which is spiritual allegory), or the Canterbury Tales (which is an estates satire).

To be more strict with the “epic” category is to recognize that it came to Western culture from a coherent corpus of Greco-Roman poetry. Tolkien wrote that “Beowulf is not an ‘epic.’… No terms borrowed from Greek or other literatures exactly fit.” Indeed, Beowulf is not the Anglo-Saxon Aeneid, nor is it the Anglo-Saxon Iliad. Greco-Roman epics were long narrative poems about heroic figures, but they were also more than that: they participated in an established epic tradition by conspicuously adopting the poetic forms, narrative styles, and thematic features of that tradition. To be familiar with this tradition of epic literature is to be familiar with ideals and imaginative experiences that are inseparable from Christian civilization, and that flourished in new and wondrous ways during the Middle Ages. To esteem that tradition is to defy the corrosive cynicism of postmodernity, which looks askance at heroism because it sees so few things as worth fighting for. And to love that tradition is to learn a life-changing, soul-saving lesson from the medieval world, which was deeply enamored of heroes—and of saints.

Let’s take a look at four venerable conventions of epic literature: a narrative that begins in medias res, the aristeia, the katabasis, and the proem.

In Medias Res

An epic poem dives right into the midst of the primary narrative; in medias res means “into the midst of things.” There’s no lengthy preamble, and readers (or listeners) must wait for flashbacks even to learn about important events that led up to the main action. This is a good way to live: duc in altum, said the Master to Simon Peter: “Put out into the deep.” Medieval culture was an in medias res culture. When the moment arrived—for knights to charge off toward the Holy Land, for monks to charge out into the wild lands of mortification, for an archbishop to charge into his cathedral despite the threat of violent death—everything else had to wait. Such was the medieval art of living an epic life.

Aristeia

From the Greek word for “prowess,” the aristeia is a poetic episode that celebrates the skill and valor of a warrior. In the Iliad, Homer gives us aristeiai for Diomedes, Agamemnon, Hector, and Patroclus, who acquit themselves admirably on the battlefield—but can’t compare to the hero, Achilles, when finally he decides to show the Trojans what he’s made of. How very different and strange is Beowulf’s aristeia, when he locks Grendel in some sort of death grip until the monster’s arm is torn off. A passage from G. A. Henty’s novel Winning His Spurs gives us an example of the real-life aristeiai that abounded in the days of sacred knighthood:

Then having, by his single arm, put to rout the Saracens at this point, he dashed through them to the aid of the little band of knights who had remained on the defensive…. All thought that they would never see him again. But he soon reappeared, his horse covered with blood, but himself unwounded; and the attack of the enemy ceased.

From the hour of daybreak, it is said, Richard [the Lionheart] had not ceased for a moment to deal out his blows, and the skin of his hand adhered to the handle of his battle-axe. This narration would appear almost fabulous, were it not that it is attested in the chronicles of several eye-witnesses.

If there must be war in the world, this is how it should be fought.

Katabasis

Meaning “descent” in Greek, katabasis in epic poetry is specifically a descent to the underworld. Odysseus’ visit to the land of the dead in the Odyssey is similar to a katabasis, and Beowulf descends into a watery underworld when he vanquishes Grendel’s mother, but the award here goes to Virgil. He immortalized the epic katabasis in Book VI of the Aeneid, which contains one of history’s most unforgettable poetic passages:

… facilis descensus Averno;

noctes atque dies patet atri ianua Ditis;

sed revocare gradum superasque evadere ad auras,

hoc opus, hic labor est.

Here it is in Dryden’s translation:

The gates of hell are open night and day;

Smooth the descent, and easy is the way:

But to return, and view the cheerful skies,

In this the task and mighty labor lies.

Going downward—physically, psychologically, intellectually, morally—is easy. To climb toward greatness, to ascend steadily unto the heights of human life when the world with all its false promises and digital simulacra is trying to drag you into a swamp of mediocrity: that’s the work of heroes.

Proem

We ought to savor the unique thrill of an epic’s proem, or introductory passage, where the poet conveys the essence of his story and—in one of my favorite literary conventions of all time—invokes the Muse, who sings through mortal men the heavenly song of the hero. The scholar and translator Robert Fagles crafted stirring English versions of Homer’s proems. His opening for the Iliad is superb:

Rage—Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles,

murderous, doomed, that cost the Achaeans countless losses,

hurling down to the House of Death so many sturdy souls,

great fighters’ souls, but made their bodies carrion,

feasts for the dogs and birds,

and the will of Zeus was moving toward its end.

The first lines of his Odyssey are also very fine:

Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns

driven time and again off course, once he had plundered

the hallowed heights of Troy.

Many cities of men he saw and learned their minds,

many pains he suffered, heartsick on the open sea,

fighting to save his life and bring his comrades home.

The proem of the Alliterative Morte Arthure, from the late fourteenth century, also includes an invocation but overall isn’t very Homeric; instead, it’s a model of how to begin each precious, ordinary day of an epic and heroic and—God willing—saintly life:

Here beginnes Morte Arthure. In Nomine Patris et Filii

et Spiritus Sancti. Amen pur Charite. Amen.

PRAY FOR TRANSLATORS! 📚🌙🌴🌊

This was a gem of an essay that made for pleasant reading. My undergraduate days go back fifty years. I said that to say this: You and Robert Kmita will be directly responsible for the goodly number of books I will acquire in 2025 to either read or re-read. I would answer the rhetorical question from your Elizabeth Barrett Browning excerpt with a succinct yes. Finally, the last sentence is just outstanding. I made the sign of the cross as I read it.