In Sunday’s post, we looked at key passages from Aristotle’s Poetics to understand the emotional, spiritual, and social significance of a specific and uniquely potent form of pain: the emotional pain that we experience through theatrical tragedy. We wondered why tragic plays, and by extension other forms of tragic literature, appeal so strongly to human nature—why do we inconvenience ourselves and even pay money to watch a disturbing and heartbreaking enactment of villainy, turmoil, death, and ruin? Why do we voluntarily place ourselves in the path of an emotional wrecking ball, when we could just stay at home and do something that makes us relaxed and happy instead of fearful and sorrowful? Why, in short, do we go to the theater seeking pain instead of pleasure?

We learned from Aristotle that when we buy tickets for a play like Othello or King Lear, we are, to some extent, seeking pleasure—a special type of psychological pleasure that comes from theatrical pain. Even more than that, we are seeking wholeness, because a morally coherent, aesthetically refined tragedy brings emotional restoration to the individual and ethical restoration to the community. The theater becomes, through the mimetic representation of sin, suffering, and death, a place where we see more deeply into the mysteries of personal and social life. By inspiring us to contemplate pain and misfortune rather than flee from it, poetic tragedy allows us to more fully understand our lives as a dance of joy and sorrow. Aristotle said that “to learn gives the liveliest pleasure, not only to philosophers but to all mankind”; through tragedy we learn about our very selves, our very nature as mortal and fallible beings, and therefore the pleasure, though it begins in pain, is great indeed.

And yet, we had to end our discussion on Sunday with the feeling that something was amiss. If drama has had so weighty and beneficial a role in the cultural life of European civilization, how could it be that during the Middle Ages, the art of the theater was dormant? How, we wondered, could medieval society flourish despite the absence of theatrical tragedy?

The answer, I believe, is quite simple: Though classical theater had faded away and Renaissance theater had not yet arrived, drama during the Middle Ages was far from absent. It was, on the contrary, exceedingly common. But what medieval society had was a rather different type of tragic drama, and it was performed in a rather different type of theater.

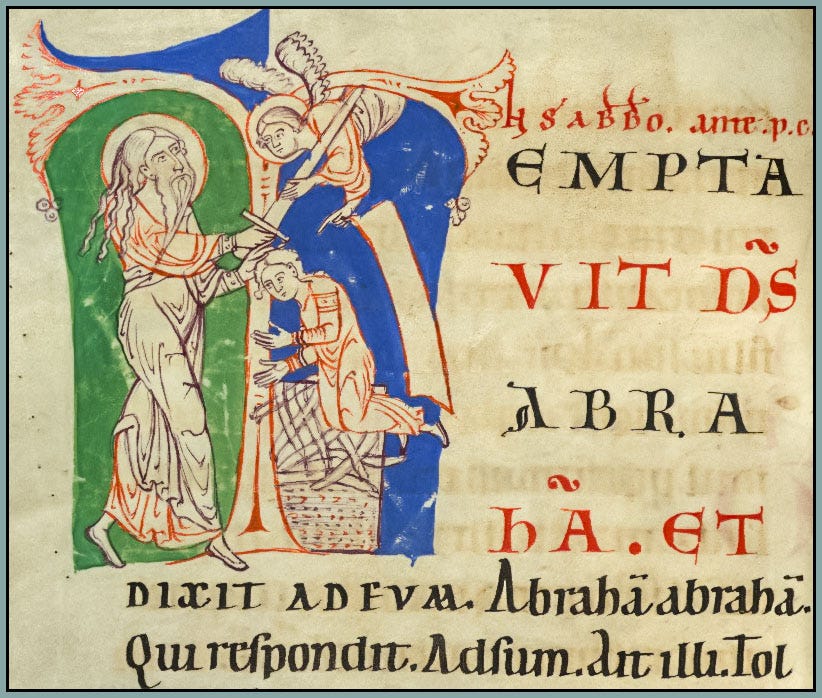

It’s the twelfth century; imagine yourself in an abbey church. The shadowy Romanesque interior draws your attention to the sanctuary, and the smooth stones, seemingly as immoveable as the earth itself, make distant voices sound near. There are sumptuously vested clerics at the altar, robed singers in the chancel, and laity standing in the nave. The celebrant seems to be in dialogue with the choir, as he moves from one noble posture to another, one expressive ritual to another, one prayer or reading or song to another. A continual movement of sacred objects accompanies the continual movement of sacred ministers, each attending to his particular task, each acting as one distinct note in an embodied harmony that brings the celebration to perfection.

While all this is happening, a larger structure, a narrative arc of sorts, emerges. The service is building toward something. A story is being told—through Latin, yes, a verbal language, but also through the language of gesture and ceremony, the language of melody and bell song, the language of incense and symbol and silence.

An emotional weight seems to be gathering; from the sanctuary come feelings of mystical urgency and reverential fear, of expectation soon to be fulfilled, of a great and heroic and sorrowful deed soon to be accomplished.

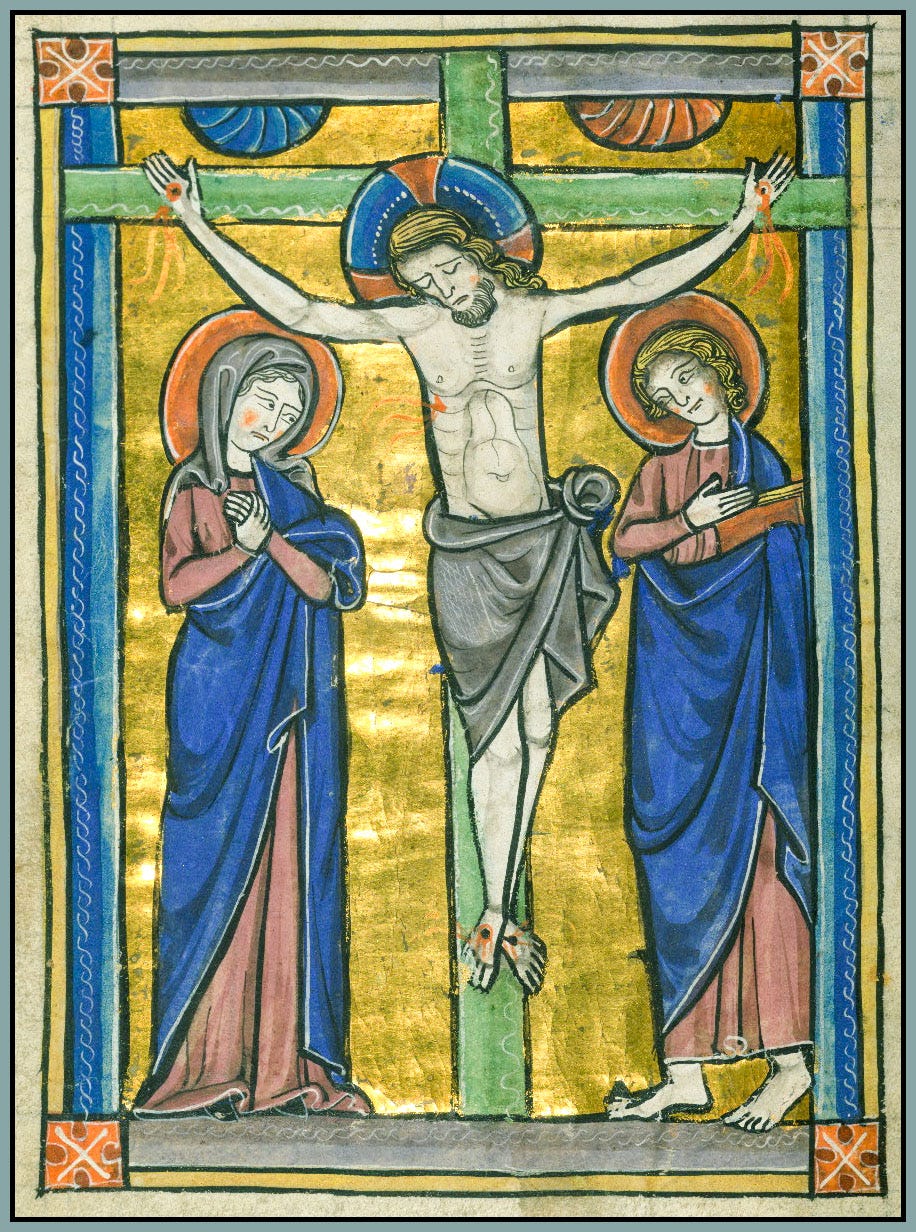

Qui pridie quam pateretur…—“Who, the day before He suffered…” There is talk of pain now, and this “He” of whom the priest speaks is known to all in attendance. There is no need to remind them that He was most cruelly betrayed.

Hoc est enim corpus meum…—“For this is My body…” The celebrant speaks in the first person now. Somehow becoming both himself and Another, he has assumed the role of Sufferer; he gives Him a body and a voice, that He might be seen and heard.

Hic est enim calix sanguinis mei, … qui pro vobis et pro multis effundetur…—“For this is the chalice of My blood, … which shall be poured out for you and for many…” Now there is violence: the shedding of blood.

…in mei memoriam facietis—“…you shall do them in remembrance of Me.” There is death, foretold. And there is death, remembered: Unde et memores, … ab inferis resurrectionis…—“Calling to mind … His Resurrection from the dead…” And in the midst of it all, there is peace, joy, pleasure, for the story ends not with death but with new and glorious life, not with darkness but with the light of self-knowledge, not with pain but with the hope of everlasting delight.

Betrayal, suffering, blood, death, redemption: This was the tragic drama of the Middle Ages. This was the public event that has been called “the central artistic achievement of Christian culture.” It spoke through both recited poetry and song, as Aristotle insisted that tragedy should; its costumes were vestments of both aesthetic and symbolic excellence; and its dance was composed of rituals so august and solemn that they surpassed the movements of mortal man, evoking instead the postures and processions of the angels in the courts of the Lord. This drama did not take place in a Greek amphitheater, nor in an Elizabethan playhouse. Its venue was every cathedral, monastery, chapel, and parish church in Christendom. Though not everywhere celebrated with the same skill and magnificence, it was everywhere the same story about the same tragic Hero, whose downfall resulted, as Aristotle required for a tragedy to be “perfect,” not “from vice, but from some great error or frailty.” This Hero’s frailty, as the Prophet Isaiah foresaw, was the greatest imaginable:

He hath borne our infirmities, and carried our sorrows: yet we did judge him as plagued, and struck by God, and afflicted. And he was wounded for our transgressions, he was broken for our sins…. The Lord hath laid upon him the iniquity of us all.

Let us return to the question with which we began: How could medieval society flourish despite the absence of theatrical tragedy? The answer is that theatrical tragedy was not absent but almost omnipresent, if we simply transpose theatrical drama into ritualized religious drama and see the eucharistic liturgy of the Middle Ages as a unifying, ennobling, cathartic tragedy of the highest order.

The idea of medieval liturgy as sacred drama is, in my view, a crucial contribution to our understanding of medieval thought and culture, and of Christian civilization in general—and of human life in general. It is by no means my invention, though I would like to develop it and make it more widely known. The idea was elaborated in compelling fashion by a highly distinguished scholar and professor named O. B. Hardison, whose research led him to make statements such as this:

The conclusion seems inescapable that the “dramatic instinct” of European man did not “die out” during the earlier Middle Ages, as historians of drama have asserted. Instead, it found expression in the central ceremony of Christian worship, the Mass.

And this:

In the ninth century the boundary … between religious ritual (the services of the Church) and drama did not exist. Religious ritual was the drama of the early Middle Ages and had been ever since the decline of the classical theater.

And this:

Should church vestments then, with their elaborate symbolic meanings, be considered costumes? Should the paten, chalice, sindon, sudarium, candles, and thurible be considered stage properties? Should the nave, chancel, presbyterium, and altar of the church be considered a stage, and its windows, statues, images, and ornaments a “setting”? As long as there is clear recognition that these elements are hallowed, that they are the sacred phase of parallel elements turned to secular use on the profane stage, it is possible to answer yes.

I must emphasize that these assertions do nothing to demean or discredit medieval liturgies. They do nothing to suggest that church services were a mere “performance” or a vain imitation of classical drama. They do not lower sacramental ceremonies to the level of fine poetry or sensational entertainment. Rather, they open our minds anew to the extraordinary richness and powerful social appeal of medieval liturgies, which in addition to being reverent and solemn, prayerful and meditative, authentic and hieratic, were also—in the best possible sense of the word—theatrical. They adopted and purified and sublimated mankind’s innate desire to gather together within a consecrated space and experience the enduring mysteries of human life in dramatic, and especially in tragic, form. And at the center of it all, made present spiritually, allegorically, and sacramentally, was the One whom the twelfth-century theologian Honorius saw as a mighty Protagonist in the dramatic contest at the altar:

After our accuser has been destroyed by our Champion in the struggle, peace is announced by the judge to the people, and they are invited to a feast. Then, by the “Ite, missa est,” they are ordered to return to their homes with rejoicing. They shout “Deo gratias” and return home rejoicing.

Those who would minimize the role of drama in the middle ages also forget the flourishing of little dramas that flowed from the Mass like Holy Week processions, Plough Monday rituals, and other paraliturgical activities that occurred outside the Church, inspired by what happened in it.

Grand opera operates and is successful at all levels, music, costume, drama, makeup, stage management, sets, through a suspension of disbelief…well understood by the lovers of grand opera, if not at a conscious level. Likewise your analysis well explains the attraction or perhaps, sense of authenticity of the tlm or traditional latin mass versus the novus ordo modernist mass to those who prefer the tlm. The former never lifts the dramatic veil, the priest, celebrants, altar boys move in military precision independent of the audience in as you say a sacred drama. The new (since 70s) modernist mass shatters the suspension of disbelief, turns on the fluorescent box store lights, faces and interacts with the parishioners/audience and pierces the veil, ruining the drama, replacing it with the pedantic. You will have to get your drama elsewhere.