The Timeless Spiritual Writings of a Medieval Mystic

C. S. Lewis, T. S. Eliot, and Julian of Norwich

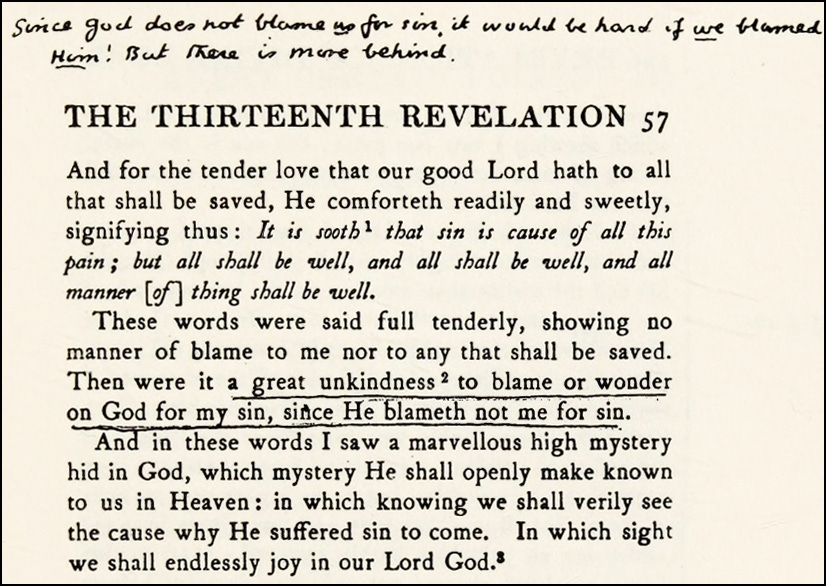

The annotation at the top of the page reads, “Since God does not blame us for sin, it would be hard if we blamed Him. But there is more behind.” The handwriting is that of C. S. Lewis, who was reading Revelations of Divine Love, by the medieval mystic Julian of Norwich, in the summer of 1940.1

This one image says much about Julian’s strangely enduring presence in English spiritual and literary culture. We might, first of all, be surprised to find that C. S. Lewis, a twentieth-century Protestant novelist and scholar, was reading and reflecting upon the words of a fourteenth-century Catholic anchoress who never received an advanced education. We could also notice the sentence in the paragraph preceding the one with the underlining: “…but all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner [of] thing shall be well.” These are the words that made Julian something of a celebrity in modern literary circles, thanks to T. S. Eliot:

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flames are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.

Those are the final lines of “Little Gidding,” which in turn is the final “quartet” in Four Quartets, a series of poems—superb, relative to other Modernist poetry—that Eliot composed in the 1930s and ’40s. Julian’s cryptic assurance that “all shall be well” appears three times in “Little Gidding” and comes heavily laden with ironic foreboding: the poem was published in 1942, when Europe was committing the collective suicide known as the Second World War, and in that very year, the Church of St. Julian’s in Norwich—where Julian the mystic lived as an anchoress—was destroyed by German bombs. All was not well in the land formerly known as Christendom, and likewise, Julian’s words are less optimistic when one observes that they are given as consolation to “all that shall be saved.” Elsewhere she says, “Sin is so vile and so much for to hate that it may be likened to no pain if that pain is not sin…. When a soul willfully chooses sin,… he has absolutely nothing. That pain [of sin] I think is the hardest hell, for he has not his God.”

Finally, the passage that Lewis underlined and commented upon captures that elusive, exploratory, sometimes even audacious or unsettling quality in Julian’s prose. It is statements like that one—“[God] blameth not me for sin”—which pique the interest of modern scholars or theologians who have a keen eye for subversive currents in the culturally placid sea of premodern society. Julian’s writings are extraordinarily rich, even potentially transformative, but they are emphatically not a catechism, not systematic theology, not doctrinal explication. They are, rather, the difficult thoughts of a holy and thoroughly medieval woman who encountered Christ and journeyed, through Him, into the deepest mysteries of human existence. She searched, she pondered, she wondered, she loved—but the boundaries were never questioned: “In all things,” she declares, “I believe as holy church teaches. For in all this blessed vision of our lord ... I understood never nothing therein that bewilders me nor keeps me from the true teaching of holy church.” We should hesitate to extract her assertions from their immediate context, and we should never estrange them from their overarching context, which is Julian’s unfailing devotion to the doctrinal structures of medieval Christianity.

Lewis said it well in his marginal note: “But there is more behind.” With Julian, there is always something more behind, and that something is “the true teaching of holy church.”

I’m serious about weaving medieval spirituality into the fabric of my postmodern life, and I’m also serious about making this newsletter a valuable resource for those who are similarly inclined. Last week we discussed something that is crucial to this process, namely, traditional sacred liturgy, which in the Middle Ages was happily wedded to the Latin language. This week I want to convey the importance of experiencing medieval spirituality through the vernacular, and to find the vernacular, we look not to liturgy but to poetic and devotional literature.

Unfortunately, medieval vernaculars are not fully accessible to non-specialists, because languages have changed a lot since the Middle Ages, even since the Late Middle Ages. English is certainly no exception, and that’s why we’re talking about Julian of Norwich today. Because her writings are so famous, they’re surrounded by various types of scaffolding—glosses, modernizations, translations, commentaries—that allow any motivated reader to explore the magnificent exterior of her spirituality and even to glimpse the beautiful, numinous, candlelit recesses within.

This doesn’t mean that reading Julian’s works will be easy, but it will, I think, be worth the effort, because the vernacular opens a medieval mind to us in a special way. Latin was not a native language for Christians of the High and Late Middle Ages. Its supreme importance for liturgy, scholarship, international relations, and cultural continuity, along with its formal excellence and natural sonority, cannot change the fact that most people were not thinking in Latin. Or if they were, those Latin thoughts were still somehow distanced from the deepest aquifers of the psyche—still somehow removed from that mysterious region of the mind where primal impulses and preverbal realities emerge, like germinating seeds, into the light of language. That is the region of the “mother tongue,” whose words and grammatical structures supply our first and irreplaceable sign system for communicating sensations, emotions, concepts, attributes, relationships—in short, Reality. Indeed, we are fortunate that knowledge of modern English still gives us some degree of competency in late-medieval English, which is the language that most fully, and beautifully, and powerfully conveys the interior world of Julian of Norwich.

Above I mentioned modernizations and translations, but I want to emphasize that those should play a supporting role only. Nicholas Watson and Jacqueline Jenkins, in their introduction to a scholarly edition of Julian’s works, speak eloquently in favor of reading her original words:

Any careful reading of writing like Julian’s has to be in Middle English, the language in which her thinking is incarnated as fully as the Christ of her revelation is incarnated in the flesh.

This next section is especially insightful; the italics are mine:

Julian’s thought is difficult in any language, but the differences between medieval and modern English have less to do with this than [with] the cultural shifts that divide her conception of what written English does from our own. More like modern lyric poetry than prose, Julian’s writing … [needs] to be read in the mouth as well as with the eye…. For all its superficial unfamiliarity, the look and sound of Middle English provide a clearer avenue than translation or modernization into the strangeness of the language as this is molded in Julian’s hands, a strangeness essential to understanding her and that translation can only destroy as it tames.

I wholeheartedly agree with this. When I first read one of Julian’s works in medieval English, I was captivated. The effect is unlike anything I’ve experienced with modern English prose, and it wasn’t immediately clear that the writing style was so central to the power of its theological and devotional message. I’ve even suspected the language of creating a sort of optical-sonic-grammatical illusion, as though Julian’s thoughts seem more compelling and profound than they really are just because the spellings are so different, and the sentence structure feels primitive, and some of the words are unfamiliar.

But I don’t think in terms of an “illusion” these days. Now I more fully appreciate the union of form and content. The spelling, the mystical obscurity, the stone-and-timber syntax, the homely turns of phrase, the rough Anglo-Saxon texture—all are part of the magic by which medieval communities made the truths of heaven resonate in the hearts of men. I also find myself more convinced that medieval writers crafted their language with a subtle artistry that, much like medieval culture in general, possesses a special ability to move the soul and enlighten the mind. Julian’s prose doesn’t have the clarity and elegance of a modern essay, and her rhetoric is not that of classical Antiquity or of the Renaissance. Her writing has something else—a sort of elemental vitality, a “spiritual rhetoric” that ultimately derives not from Greco-Roman oratory but from the Spirit who, as St. Paul said, “intercedeth for us with unspeakable groanings.”

I’ll conclude today’s post with a practical guide to reading Julian of Norwich, and then on Tuesday we’ll take a detailed, meditative look at a Middle English passage on prayer, from her longer treatise.

And that brings us to the works that Julian composed. To make a long story short, Julian wrote two books based on her visionary experiences. The first, completed perhaps in the 1380s, is the shorter of the two. Following Watson and Jenkins, we will call this one A Vision Showed to a Devout Woman. The second and longer text, which may have been completed much later in her life, expands upon the first and offers a more speculative exploration of the Christian religion. Again following Watson and Jenkins, we will refer to the longer text as A Revelation of Love. Both are excellent; I think it makes sense to start with A Vision Showed to a Devout Woman, but it’s easier to find Middle English versions of A Revelation of Love.

Unfortunately, the titles chosen by publishers don’t clearly indicate which text has been used, and to increase the confusion, there are significant differences between two important manuscripts (called “Sloane 1” and “Paris”) containing A Revelation of Love. The list below provides some information on editions currently available,2 and I’ll conclude with two tips: First, read slowly, not only because Middle English is difficult, but also to imitate medieval reading, most of which was probably more vocal and more meditative than modern reading. Second, read as if you’re listening to Julian speak to you—she wrote for “alle mine evencristene” (“all my fellow Christians”), so if you consider yourself a Christian, then she wrote for you.

The Showings of Julian of Norwich (Norton critical edition, edited by Denise Baker): This is an annotated, Middle English version of A Revelation. It is relatively affordable and includes a helpful introduction and glossary.

The Shewings of Julian of Norwich (Medieval Institute Publications, edited by Georgia Crampton): This is a free, online, annotated version of A Revelation in Middle English. It is based on Sloane 1, whereas Norton preferred the more modernized language of the Paris manuscript.

The Writings of Julian of Norwich (edited by Nicholas Watson and Jacqueline Jenkins): This is the edition I mentioned above. It has Middle English versions of A Vision and A Revelation, with extensive annotations.

Revelations of Divine Love and The Motherhood of God (translated by Frances Beer): This book includes a modern English version of A Vision.

Revelations of Divine Love (Oxford World’s Classics, translated by Barry Windeatt): This includes modern English versions of A Vision and A Revelation.

The Complete Julian of Norwich (by John-Julian, OJN, an Episcopal clergyman): According to the publisher’s description, this includes “a modern translation of all of Julian’s writings” along with analysis and “historical, religious, and personal background material.”

Revelations of Divine Love (edited by Dom Roger Hudleston, a Benedictine monk, available for free on HathiTrust): This is a modernized version of A Revelation, but the editor attempted to keep the modernized text close to the medieval text.

The image is reproduced from John Lawlor’s C. S. Lewis: Memories and Reflections (Spence, 1998).

Your writing is amazing.

Thanks, Robert -- I'm enjoying this series so much! I've loved Julian of Norwich since I was an Episcopalian (no idea why Anglicans love her so much, but they do -- CS Lewis wasn't an exception!)