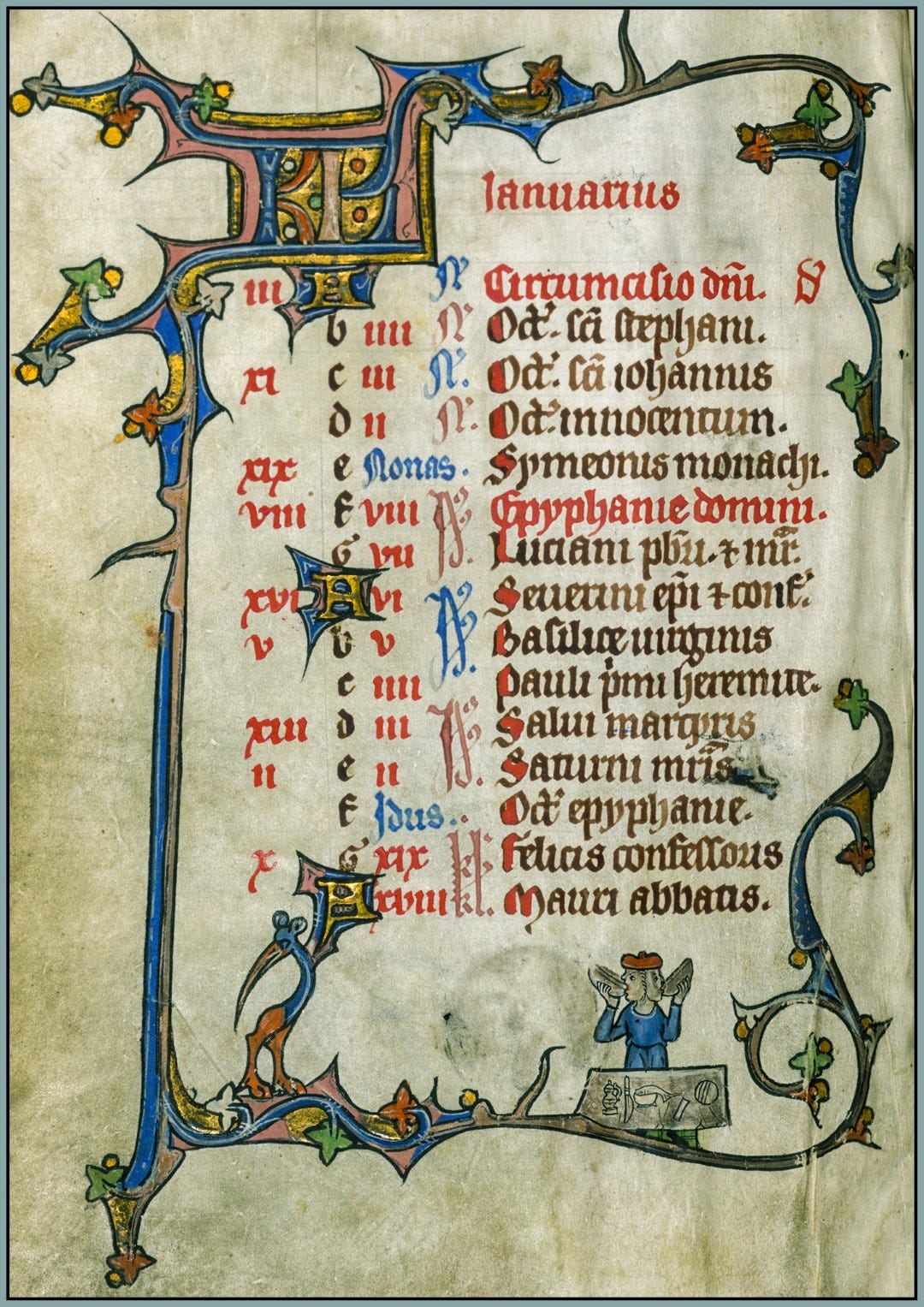

The Medieval Year, a regular feature of the Via Mediaevalis newsletter, gives us an opportunity to appreciate calendrical artwork from the Middle Ages, reflect on the basic tasks and rhythms of medieval life, and follow the medieval year as we make our way through the modern year. You’ll find helpful background information in these posts:

“Poetry may … wonder and complain that she is become so wholly (almost) a heathen. We think nothing speeds well that is not undertaken with the Invocation of I know not what Idols, neither doth any thing sound well that is not graced with some of Ovid’s gross fables of their esteemed gods.”

—William Scott (d. 1617)

A truly striking and edifying feature of medieval society is its comfort with, and measured admiration for, the culture of pagan Antiquity. In the era of the early Church, the classical world was regarded with greater hostility, especially in the west. The second-century bishop Theophilus, for example, scorned and rejected classical culture. Tatian, a disciple of Justin Martyr, condemned classical culture in its entirety. Tertullian, revered as the “father of Latin Christianity,” did likewise. The fourth-century apologist Arnobius inveighed against pagan philosophy, Augustine compared the pagan authors to the Egyptians who oppressed the Israelites, and Jerome related a dream in which angels scourged him and said, “You are not a Christian, you are a Ciceronian.” All this is understandable: Greco-Roman paganism was still a serious threat to the salvation of souls and to the Christian social order, and it was treated as such. Ovid’s poetry may have been some of the finest Latin verse ever written, but if the choice is between Ovid and heaven, the Metamorphoses goes straight to the bonfire.

By the end of the Middle Ages, pagan mores are back in style, and we see Renaissance Christians acting as though the culture of Antiquity, rather than the redemptive grace of Christianity, will save the world. As suggested by the epigraph to this article, though, post-medieval Europe also wandered in the other direction, with puritanical modes of thought disdaining secular (or even religious) art as a tangled web of falsehoods, vanities, and sensual temptations.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Via Mediaevalis to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.