There Is No Feast without Symbol

Modern maladies, and a medieval remedy

After this dream he saw another vision:

He was in France, at Aix, in his chapel;

his right arm is gnawed by a vicious bear.

Out of Ardennes a leopard was coming;

it attacks his body ferociously.

And from the hall a hunting-dog came,

leaping and running toward Charles.

It tore the right ear of the vicious bear;

in fury the leopard next it fights.

Of a mighty battle the Franks then speak;

which will be victor, they know not.

Charles sleeps on, awakening not.

Today begins one of the most important discussions we will have here at Via Mediaevalis. The topic is symbolism, which if understood fully—if understood as medieval communities experienced it—will fundamentally change your life.

Symbolism entered my intellectual world perhaps in much the same way as it entered yours. High school English teachers explained to me that symbols are things that novelists put in their stories, presumably to make them more complicated, or clever, or something. For example: The green light at the end of Daisy’s dock in The Great Gatsby isn’t just a green light. It also has some sort of special meaning. It signifies something profound, or philosophical, or emotional—Gatsby’s hopes and dreams, according to SparkNotes.com and LitCharts.com; or maybe “the unreachable dream that lives inside all people,” as PrepScholar.com would have it; or even “the inability to recapture the past,” as CollegeTransitions.com explains. For me, as a pretty typical teenager in an American public school, what it signified was the tiresome complexity of books that were often long and boring, the importance of reading the commentary (not just the summary) in the CliffsNotes, and the fear that I might have to write an essay about symbolism in The Great Gatsby.

The first problem with all this is that symbols feel contrived and utilitarian; one might imagine F. Scott Fitzgerald at his writing desk, pencil in hand, as he tries to think up enough symbols to ensure that his story will qualify as “literature” and therefore make him famous. The more serious concern, though, is that it teaches young people, in their most intellectually formative years, that symbols belong in books—and more specifically, in fictional books, which can have things like symbols because the tales they tell are not real.

We’re going to work through this topic gradually, and it will take some time to arrive at the far-reaching, overarching ideas that I want to share with you. However, I’ll try to draw the basic outline of our destination now, so that you have a feeling for where we’re headed:

Symbols don’t belong only, or even primarily, in books. The truest realm and richest treasury of symbols is the place where you are right now: the material world.

Symbolism is not something that makes a fictional story less “real.” Rather, symbolism makes the factual world more real.

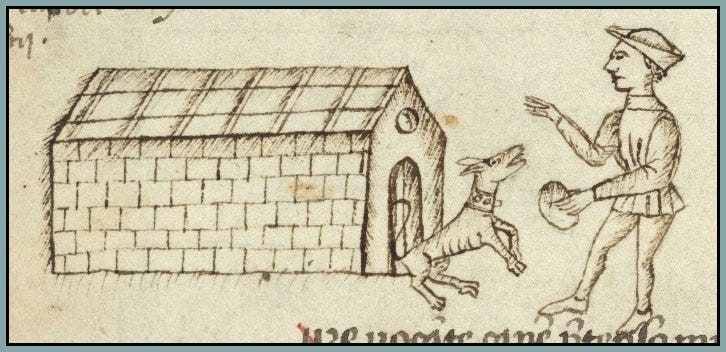

The epigraph to this essay is laisse 57 from the Song of Roland, one of medieval France’s most admired and cherished works of literature. Charlemagne’s vision, presented by the poet as a tapestry of symbolic creatures and actions, gives us insight into the mysterious, symbolic texture of medieval life. The bear, the leopard, the dog—animals had symbolic meanings in the Middle Ages. Places also carried layers of significance, and we see that the poet is careful to mention the chapel, Ardennes, and the hall. The body also was a highly symbolic entity, and twice in the vision a wound is inflicted on the right side: first Charlemagne’s right arm, then the bear’s right ear.

Another thing to notice in this passage is that symbolism exists in a liminal state somewhere between comprehensibility and incomprehensibility. The general symbolic meaning is clearly implied—Charles and the beasts are caught up in a violent fray, which represents a “mighty battle” involving the Franks, and the dangerous wild animals contrast with the dog, a domestic creature valued for its loyalty and service to mankind. But why are the attackers a bear and a leopard? Why does the bear lose an ear? No explanation is given, and the next laisse begins abruptly with the action of the following morning. The reader—or in the case of the original audiences, the listener—is left to ponder the vision and find in its obscurity a sense of wonder, which as we saw in a previous post, is where spiritual wisdom begins.

Finally—and this is crucial—there is no boundary between the material and symbolic realms:

It tore the right ear of the vicious bear;

in fury the leopard next it fights.

Of a mighty battle the Franks then speak;

which will be victor, they know not.

Charles sleeps on, awakening not.

The poet creates a seamless transition from the symbolic battle to the physical battle. Are the Franks in the vision, or outside of it? Or both?

Where does the symbol end, and reality begin?

A feast without song and music, without the visible form and structure of a ritual, without imagery and symbol—such a thing simply cannot even be conceived.

—Josef Pieper

The reputation of the modern world, and especially of the postmodern world, is weighed down by a long list of grievous accusations—it’s inhuman, fragmented, oppressively fake, socially dysfunctional, etc., and afflicted by chronic malaise, isolation, stress, self-obsession, etc. These assessments don’t originate only from the quarters that you might expect. Mainstream scholars, or what we might call “public intellectuals,” sometimes speak quite strongly on this matter. A few examples will suffice:

The depthless, styleless, dehistoricized … surfaces of postmodernist culture are not meant to signify an alienation, for the very concept of alienation must secretly posit a dream of authenticity which postmodernism finds quite unintelligible.

—Terry EagletonWe need information to be silenced. Otherwise, our brains will explode. Today we perceive the world through information. That’s how we lose the experience of being present. We are increasingly disconnected from the world. We are losing the world. The world is more than information, and the screen is a poor representation of the world. We revolve in a circle around ourselves.

—Byung-Chul HanLiving in the modern world is more like being aboard a careering juggernaut … than being in a carefully controlled and well-driven motor car.

—Anthony GiddensThere is not much talking now. A silence falls upon them all. This is no time to talk of hedges and fields, or the beauties of any country. Sadness and fear and hate, how they well up in the heart and mind, whenever one opens the pages of these messengers of doom.1 Cry for the broken tribe, for the law and the custom that is gone. Aye, and cry aloud for the man who is dead, for the woman and children bereaved. Cry, the beloved country, these things are not yet at an end.

—Alan Paton

Let us compare all this to what another scholar said in a truly remarkable description of late-medieval and early-modern England:

“Merry England” was merry chiefly by virtue of its community observances of periodic sports and feast days. Mirth took form in morris-dances, sword-dances, wassailings, mock ceremonies of summer kings and queens and of lords of misrule, mummings, disguisings, masques—and a bewildering variety of sports, games, shows, and pageants improvised on traditional models. Such pastimes were a regular part of the celebration of a marriage, of the village wassail or wake, of Candlemas, Shrove Tuesday, Hocktide, May Day, Whitsuntide, Midsummer Eve, Harvest-home, Halloween, and the twelve days of the Christmas season ending with Twelfth Night. Custom prescribed, more or less definitely, some ways of making merry at each occasion.

—C. L. Barber

As the great modern philosopher Josef Pieper understood, a society without symbolism is a society without celebration, festivity, fellowship—that is to say, without joy.

We will explore, in the articles that follow, the question of why this is so.

Here the author refers to newspapers. Nowadays, messengers of doom come in both physical and electronic forms.

I’m looking forward to the exploration.

Great essay! The bit about Great Gatsby is spot on lol