What Fire and Sword Cannot Unmake

The classical ancestors of medieval poetry.

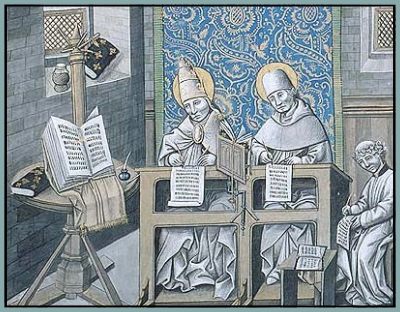

We’re continuing our introduction to medieval poetry, and after exploring the nature of poetic art and the preeminence of the Psalms, we’re ready to consider the non-biblical ancient writers who inspired medieval poets.

This discussion is an essential prelude to studying medieval poetry itself, because it helps us to remember something crucial: poetry in the Middle Ages was not primarily about innovation, originality, or experimentation. These were not prominent medieval values in general, but one might think that poetry was an exception—since the poetic experience in modern and postmodern culture seems to revolve around an amorphous core composed largely of innovation, originality, and experimentation. We can ponder, as one of countless examples, the three final stanzas of “Morning Song” (published in 1960):

All night your moth-breath

Flickers among the flat pink roses. I wake to listen:

A far sea moves in my ear.One cry, and I stumble from bed, cow-heavy and floral

In my Victorian nightgown.

Your mouth opens clean as a cat’s. The window squareWhitens and swallows its dull stars. And now you try

Your handful of notes;

The clear vowels rise like balloons.

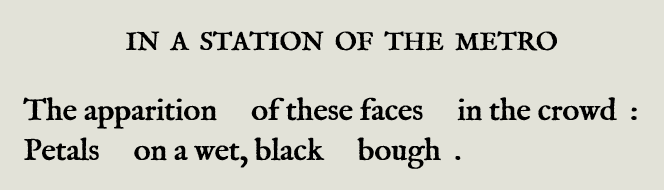

This was written by Sylvia Plath, whom Poetry Foundation describes as “one of the most dynamic and admired poets of the 20th century.” I pass no judgment on her verse or talents; the poor woman killed herself in disturbing fashion at age 30, so whatever fame she may have attained was unenviable in the extreme. I also am not highlighting this as an instance of wildly experimental modern poetry. In fact by twentieth-century standards it is rather traditional—it’s not completely incomprehensible, and the entire poem maintains a pleasantly regular pattern of three-line stanzas. We can find something a bit more “original” or “innovative” in the work of Ezra Pound, another famous twentieth-century poet:

The merits and demerits of modernist poetry are a topic for another day. My point here is to emphasize that the modern poetic ethos—preoccupied as it is with casting off the formal and thematic traditions of Western literature—was utterly foreign to medieval culture. This is not to say that medieval poets shunned creativity; the very word “poem” (poema in Latin) derives from Greek poiein, which means “to make” or “to create.” Long ago, English poets were called “makers,” and even the Old English word for “poet,” scop, may be related to the verb scieppan, meaning “to shape” or “to make.”

The poet as “shaper” is an apt analogy for medieval poesy; this old-fashioned but useful term suggests not so much poetry itself as the art of producing poetry. In the words of Ben Jonson, a seventeenth-century playwright whose renown was once second only to Shakespeare’s, “A poem … is the work of the poet, the end and fruit of his labour and study. Poesy is his skill or craft of making.”

The poets of the Middle Ages did not attempt to create ex nihilo, as God did. Nor did they indulge in literary experiments that are more likely to produce a monster than a masterpiece. Nor did they make verses by dismantling the artifacts of the past and reassembling them into something “unlike anything the world has ever seen,” to borrow one of modernity’s well-worn accolades. Rather, they received the works of the past and reshaped them into poems that resonated with the aesthetics, languages, ideals, experiences, and spirituality of a thoroughly feudal and Christian civilization. Medieval poesy was a marriage of creativity and respect for tradition. It balanced the powers of the imagination with reverence for the historical realities of Antiquity. It was “like unto a householder, which bringeth forth out of his treasure, things both new and old.”

That one is Homer, Poet sovereign;

He who comes next is Horace, the satirist;

The third is Ovid, and the last is Lucan.

This stanza from the fourth canto of Dante’s Inferno is a good summary of the classical influence on medieval poetry, with two caveats: First, the most important author in this group, Virgil, isn’t mentioned—because Virgil is the one speaking the lines. Second, Homer’s influence was strong but indirect. Ancient Greek texts all but vanished from the western European literary scene during the Middle Ages. Dante knew of Homer but couldn’t read his works, which were written in a language he didn’t understand and were not available in translation.1 But proficiency in Latin was widespread among the educated class, and this brought the venerable corpus of Roman poetry—read and appreciated in its original language, no less—into close contact with medieval culture.

In this essay we’ll focus on Virgil and Ovid, and more specifically, on their most momentous literary achievements: the Aeneid and the Metamorphoses. If we must choose the two classical texts that left the deepest impression on medieval poetics, they should, I believe, be these.

Virgil wrote the Aeneid in the first century BC. It recounts the journey of its hero Aeneas out of defeated Troy, over to Sicily and Carthage, back to Sicily, and finally north to western Italy, where he founded a city that wasn’t Rome itself but was an ancestor of Roman civilization. Saint Augustine, whose life and thought were seminal for medieval culture, knew the Aeneid well and used it as an allegorical framework for the spiritual journey that brought him to Christianity:

I was obliged to learn the wanderings of Aeneas, and yet I was forgetful of my own wanderings. I learned to weep for the death of Dido, because she killed herself for love, while in the midst of these things I was miserable and dying, separated from Thee, my God and my Life, and I shed no tears for myself.2

The Aeneid united stylistic excellence to subject matter that was profound, poignant, and edifying. Virgil was the renowned master of finely crafted Latin verse, and his hero was the quintessential Roman—a man of supreme pietas, which meant much more than religious piety. Roman pietas was loyalty, fidelity to one’s duty, gratitude to one’s parents, love for one’s homeland. The Aeneid gave writers of the Middle Ages a memorable and compelling example of poetry at its best: imaginative yet traditional writing in which good actions and true ideas are enriched by beautiful language. His centrality to medieval literature can hardly be overstated; as medievalist and professor Justin Haynes expressed it,

Virgil is an ideal focal point for exploring medieval imagination because his oeuvre … shaped every literate mind from Late Antiquity to the Renaissance.

The Aeneid is still worth reading—as an epic journey through the legendary origins of Rome and romanitas, as insight into medieval civilization, or even just for enjoyment. One of the best English translations ever made (and I’ve sampled quite a few) is available for free on Google Books.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses is a collection of classical myths in which many separate tales are woven together by a thematic thread that gives the poem its name: metamorphosis, or what we would more commonly call transformation. I would go further, however, and say that transformation is more than just a leitmotif in this poem: the Metamorphoses is a vivid, remarkably diverse, rhetorically magnificent depiction of human life as fundamentally a story of transformation:

In all the world there is not that which standeth at a stay.

Things ebb and flow: and every shape is made to pass away.3

Though a passionate and sometimes risqué poem, the Metamorphoses was enthusiastically read and studied by medieval monks, teachers, students, and courtiers from all over western Europe. It was an enchanting case study in Latin grammar, an exemplar of superb poetic style, and a vast treasury of delightful stories to be moralized and spiritualized through allegorical interpretations.

Poetry, broadly understood, was everywhere in medieval Europe—not just in formal works of literature but in prayer, public worship, architecture, visual arts, folk culture, agriculture, religious drama, social gatherings, and courtly entertainments. Perhaps Ovid contributed to this thoroughly poetic disposition; perhaps the Metamorphoses helped readers, artists, scholars, and saints of the Middle Ages to believe that only through poetry can the noblest moments, greatest mysteries, highest truths, and deepest loves of human life be shared. For at the end of the poem’s final book, after almost twelve thousand lines in which “every shape is made to pass away,” Ovid reveals to us one thing that does not pass away. It is the poetry itself:

And now a great work I have completed,

which not the ire of Jove, nor fire nor sword,

nor devouring old age can unmake.

Whenever it will, let that day—

which only over this body hath power—

let that day bring an end for me

to life’s uncertain span.

In my better part, however, I, immortal,

shall be borne above the stars on high,

and my name shall never die.

The closest thing to a Latin version of Homer’s epics was the Ilias Latina. I’ve never read it; here’s a description from Eleanor Dickey, a professor of classics at the University of Reading: “Written probably by one Baebius Italicus during the reign of Nero, this short Latin translation of the Iliad is essentially classical in style, with many Vergilian and Ovidian idioms. A reduction of the entire Iliad [which was over 15,000 lines] to 1070 lines inevitably reads like a summary and lacks most of the depth of the original…. Since during the middle ages Baebius’ version rather than Homer’s was the Iliad known in western Europe, Baebius’ choices have had a significant impact on the history of the Trojan myths” (source).

Confessions, I.13.

See Book 15; translation adapted from that of Arthur Golding, published in 1567.

Thank you for the Aeneid link - you have piqued my interest with this fine introduction. On a different topic, I just found a printed copy of something you wrote about St John of the Cross, where you translated a part of one of his poems and gave a summary of his life. I had been moved by the article and stuck it into an out-of-print bio of the Saint, which I just finished. What an amazing man! Talk about poetry... will you write more about his writings in the future?

Well, this is also very fine. I see I may have to refrain from excessive commenting here. I’d just like to put in a word for a few poets who combine difficult aspects of modernism with respect for the tradition; T. S. Eliot and David Jones. Jones in particular works in an aesthetic that is both deeply influenced by the medieval artisan and by the entropic fragmentation of a society in flight from God. And also, in passing, the much maligned husband of Plath, Ted Hughes, late in life rendered the excellent Tales from Ovid.