In a recent Substack post,

examined, with his usual cogency and scholarly rigor, the two different numbering systems used in the Book of Psalms. His article will be of interest to those who enjoy studying or praying the Psalms, and also those who have a general interest in Bible translations and the English-language biblical tradition. However, there is more at stake in that topic than the numbering systems themselves, and you’ll find that the article branches out into themes—fidelity to inherited customs, respect for the ancient past, cultural wholeness—that also inform the work that we do at Via Mediaevalis.I had the opportunity to discuss this article with Dr. Kwasniewski before it was published, and one question that I ended up pondering was, Why are the Psalms so rarely numbered in medieval prayer books? For example:

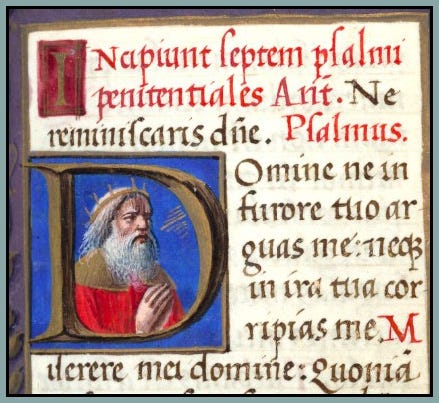

This is the beginning of a “Penitential Psalms” section—it has a fine illustration, but no number indicating which Psalm is about to be prayed.

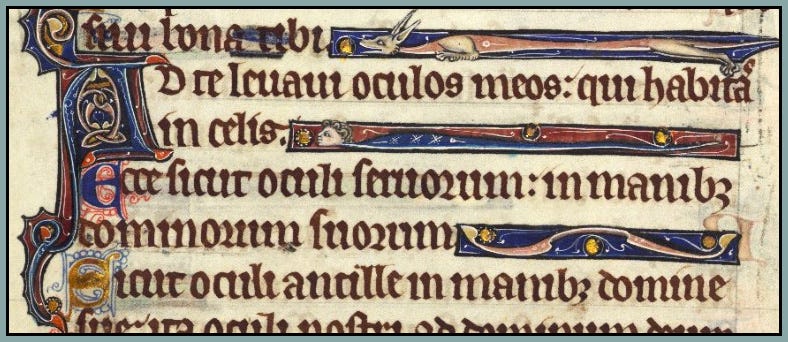

This next example has no title and no number but does offer the reader some deeply mystifying decorations:

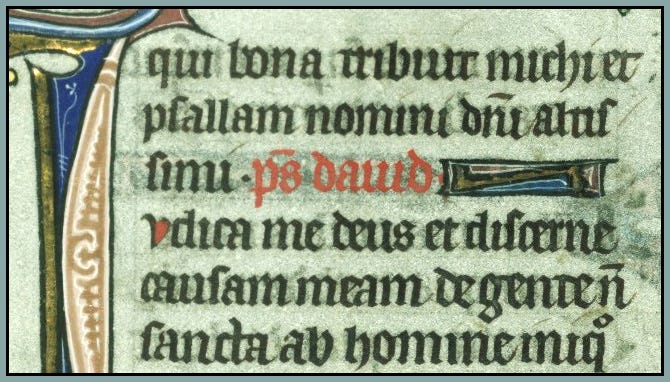

Sometimes the beginning of a Psalm was marked by a label or section title written in red ink, but the number of the Psalm is nowhere to be found:

In that last example, which by the way has a beautiful and delightfully legible script, a rather extensive red-ink title states “[here] begin the seven penitential psalms,” and the first Psalm in the sequence is marked with “Psalmus,” but still there is no number!

Why were medieval “publishers,” and presumably medieval readers as well, so decidedly uninterested in Psalm numbers? Were the numbers really so utterly superfluous? Would they not at least have been useful enough to justify a few more drops of red ink?

I don’t think anyone has a complete and definitive answer to these questions, but it occurred to me that we have a partial explanation in the very nature of medieval numbers. And this brings us back to our ongoing discussion—make sure to read the previous post, if you haven’t already—about symbolism.

The absence of Psalm numbers in prayer books was, I think, a reflection of numerical culture in the Middle Ages. In a world that taught Latin grammar as the foundation of the intellectual life, did not rely upon mathematically precise technology, and held a large portion of its wealth in the form of land and treasure, numbers were not seen as a solution to life’s problems. Most people didn’t think in highly mathematical ways, and as one author observed, many medieval folks seemed to be “poor at counting.” If you think that modern statistics are unreliable, try reading the descriptive account that Guillebert de Metz—an educated man—wrote about fifteenth-century Paris. Somehow he ascertained that Paris had “more than four thousand wine shops, more than eighty thousand beggars, and more than sixteen thousand scribes”—at a time when the city’s entire population was about one hundred thousand.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Via Mediaevalis to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.