A Comparison of Beowulf Translations

Three passages in four translations, with cultural and spiritual insights from Peter Ramey

My objective in this post is twofold: I want to provide a sampling of Beowulf editions for those who don’t currently have a favorite translation or are interested in trying a new one, and I also want to draw attention to the special qualities of, and illuminating commentary in, The Word-Hoard Beowulf, by Peter Ramey. The three editions I’ve chosen in addition to Ramey’s are those of Howell D. Chickering (first published in 1977), Seamus Heaney (1999), and Stephen Mitchell (2017). I want to be clear that these are all respectable, poetically competent translations; I didn’t choose them just to point out their inadequacies.

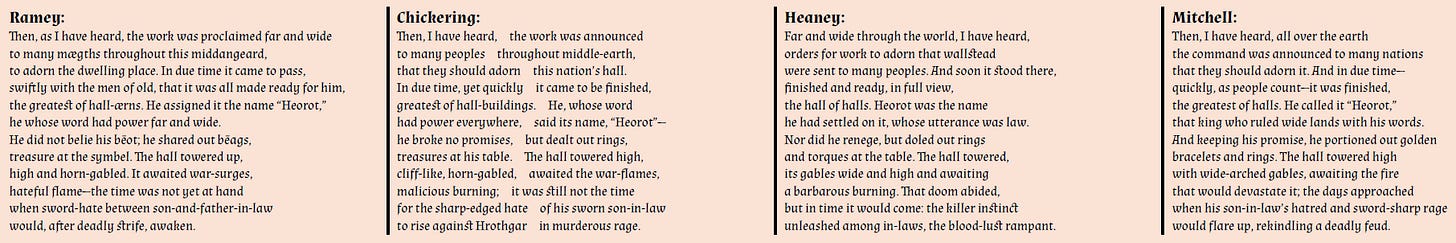

This article is divided into three sections that contain an original Old English passage from Beowulf and four translated versions of that passage. I offer some brief reflections on each version and explore the deeper meanings of the passage with help from Ramey’s footnotes. To make line-by-line comparisons easier, I included images (click to enlarge) with the four translations in parallel.

You will notice that the Old English texts and the Chickering translations have wide spaces in each line. These indicate the two half-lines (called hemistichs) that were, in the standard metrical form of Anglo-Saxon poetry, separated by a caesura and linked by alliteration. This “alliterative verse” lacks the accentual-syllabic meter and rhyme schemes that became central to the poetry of late-medieval and modern English, and consequently, it doesn’t sound particularly poetic to those whose literary sensibilities have been formed by English verse of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries.

Nonetheless, the performance of Old English poetry must have brought out a sort of primal musicality that would appeal to listeners of any era. You might feel some of this effect in the video below, which gives one scholar’s conjecture as to what Beowulf was like when recited before a rapt audience of Anglo-Saxon lords and ladies.

Passage 1: Lines 74–85

Þā ic wīde gefrægn weorc gebannan

manigre mǣgðe geond þisne middangeard,

folcstede frætwan. Him on fyrste gelomp

ǣdre mid yldum, þæt hit wearð ealgearo,

healærna mǣst; scōp him Heort naman,

sē þe his wordes geweald wīde hæfde.

Hē bēot ne ālēh, bēagas dǣlde,

sinc æt symle. Sele hlīfade

hēah ond horn-gēap: heaðowylma bād,

lāðan līges; ne wæs hit lenge þā gēn

þæt se ecghete āþumsweoran

æfter wælnīðe wæcnan scolde.Ramey:

Then, as I have heard, the work was proclaimed far and wide

to many mægths throughout this middangeard,

to adorn the dwelling place. In due time it came to pass,

swiftly with the men of old, that it was all made ready for him,

the greatest of hall-ærns. He assigned it the name “Heorot,”

he whose word had power far and wide.

He did not belie his bēot; he shared out bēags,

treasure at the symbel. The hall towered up,

high and horn-gabled. It awaited war-surges,

hateful flame—the time was not yet at hand

when sword-hate between son-and-father-in-law

would, after deadly strife, awaken.mægth: tribe, people-group

middangeard: “Following Tolkien, most translators render it ‘middle-earth,’ though geard in fact means ‘inhabited enclosure’ (from which we get yard)” (Ramey, p. 27).

ærn: house, building

bēot: a heroic vow

bēag: a ring-shaped treasure

symbel: a drinking banquet

This passage describes the construction of Heorot, King Hrothgar’s magnificent mead hall. As Ramey explains, “its importance for the poem would be hard to overstate” (p. 26), and perhaps by retaining the Old English word ærn he draws attention to its special significance (though ærn was an ordinary word used for a wide variety of structures: bæþærn = bathhouse, hordærn = treasury, etc.). Heorot in Beowulf is much more than a place for gathering and partying. It was, rather, an architectonic symbol of the power of the Scyldings, and furthermore, it was a semi-sacred space that may have provoked such intense hostility from Grendel in part because it was akin to a sanctuary.

Old English bēot is often translated as “boast,” but this is misleading because bēot has no negative connotation and stems not from arrogance or pride but from heroic valor. A bēot was a solemn vow, spoken aloud, that played an important role in Germanic warrior culture as “a promise to carry out a particular act of daring or die in the attempt” (p. 53). The lack of a satisfying equivalent in modern English leads Ramey to retain the original term.

The vigorous diction and elemental imagery in Ramey’s rendering—“high and horn-gabled,” “war-surges,” “hateful flame,” “sword-hate”—convey the strength and mystique of the early-medieval, Anglo-Saxon culture from which Beowulf emerged.

Chickering:

Then, I have heard, the work was announced

to many peoples throughout middle-earth,

that they should adorn this nation’s hall.

In due time, yet quickly it came to be finished,

greatest of hall-buildings. He, whose word

had power everywhere, said its name, “Heorot”—

he broke no promises, but dealt out rings,

treasures at his table. The hall towered high,

cliff-like, horn-gabled, awaited the war-flames,

malicious burning; it was still not the time

for the sharp-edged hate of his sworn son-in-law

to rise against Hrothgar in murderous rage.This is also an excellent translation, with a pleasing sense of balance in the hemistichs and some especially well-crafted phrases. I like the way that Chickering’s syntax evokes the stark power of the royal voice—“He, whose word / had power everywhere, said its name, ‘Heorot.’” The phrases “malicious burning” and “murderous rage” feel a bit overwrought to me.

Heaney:

Far and wide through the world, I have heard,

orders for work to adorn that wallstead

were sent to many peoples. And soon it stood there,

finished and ready, in full view,

the hall of halls. Heorot was the name

he had settled on it, whose utterance was law.

Nor did he renege, but doled out rings

and torques at the table. The hall towered,

its gables wide and high and awaiting

a barbarous burning. That doom abided,

but in time it would come: the killer instinct

unleashed among in-laws, the blood-lust rampant.Heaney departs too much from the text and the tone of the original. I don’t like the word “torques,” which makes me think of a mechanic’s shop; “dole” also has distracting connotations; the culturally important reference to “middle-earth” is lost; the “horn-gabled” imagery is also lost; “killer instinct” is strangely modern and perhaps reminiscent of a horror movie; “among in-laws” is unnecessarily vague; and I see no justification in the original for “blood-lust rampant.”

Mitchell:

Then, I have heard, all over the earth

the command was announced to many nations

that they should adorn it. And in due time—

quickly, as people count—it was finished,

the greatest of halls. He called it “Heorot,”

that king who ruled wide lands with his words.

And keeping his promise, he portioned out golden

bracelets and rings. The hall towered high

with wide-arched gables, awaiting the fire

that would devastate it; the days approached

when his son-in-law’s hatred and sword-sharp rage

would flare up, rekindling a deadly feud.Mitchell’s rendering favors readability to an extent that the poetry’s sense of authenticity is diminished. “Rekindling a deadly feud,” for example, is more of an explanation than a translation, and consider this clause: “The hall towered high / with wide-arched gables, awaiting the fire / that would devastate it.” The smooth, modern English feels rather flat and informative compared to the visceral intensity of a more literal rendering: “The hall towered / high and horn-gabled, awaited cruel surges / of hateful fire.”

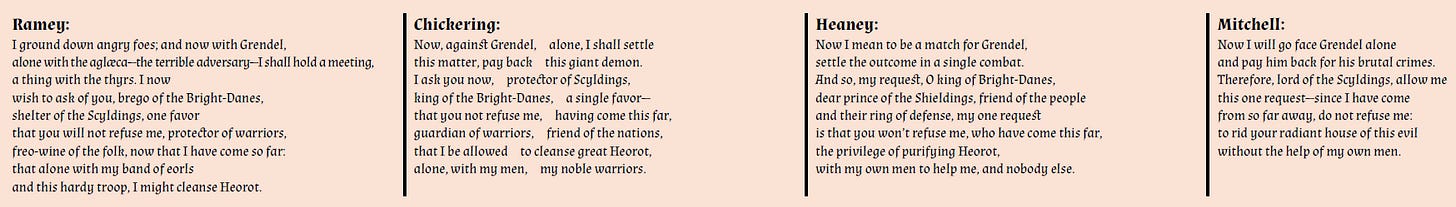

Passage 2: Lines 424–432

forgrand gramum; ond nū wið Grendel sceal,

wið þām āglǣcan, āna gehegan

þing wið þyrse. Ic þē nū þā,

brego Beorht-Dena, biddan wille,

eodor Scyldinga, ānre bēne;

þæt þū mē ne forwyrne, wīgendra hlēo,

frēo-wine folca, nū ic þus feorran cōm,

þæt ic mōte āna ond mīnra eorla gedryht,

þes hearda hēap, Heorot fǣlsian.Ramey:

I ground down angry foes; and now with Grendel,

alone with the aglæca—the terrible adversary—I shall hold a meeting,

a thing with the thyrs. I now

wish to ask of you, brego of the Bright-Danes,

shelter of the Scyldings, one favor

that you will not refuse me, protector of warriors,

freo-wine of the folk, now that I have come so far:

that alone with my band of eorls

and this hardy troop, I might cleanse Heorot.aglæca: a ferocious or awe-inspiring opponent; here Ramey retains an Old English word that isn’t perfectly understood and is rather paradoxical, insofar as it is applied to both a monstrous foe like Grendel and (in one instance) a hero like Beowulf.

thing: meeting, assembly

thyrs: a giant, malicious creature

brego: ruler, lord

freo-wine: lord-and-friend

eorl: man, warrior

Here Beowulf is addressing King Hrothgar and requesting permission to confront Grendel, who has terrorized Heorot.

“The hero speaks ironically of having a thing—a formal meeting or judicial assembly—with Grendel, here called a thyrs, underscoring through grim humor that with infernal foes such as Grendel the normal rules of human engagement do not apply” (Ramey, p. 48).

In the Old English, the final word in this passage is fælsian. Though in this case Ramey provides a translation (“cleanse”), he reveals the extraordinary significance of the original word in a footnote: “The verb employed here is fælsian, to ritually cleanse, purify, purge, a rare term with distinctly religious overtones.” It indicates spiritual purification of a holy place (such as the semi-sacred space of Heorot), and “along with Beowulf, only Christ and St. Matthew are said to carry out the sacral purification denoted by fælsian, a fact that heightens the spiritual dimension of Beowulf’s role” (p. 48). Indeed, with insights like these we see all the more clearly that Beowulf is a compelling Christ figure who unites the salvific heroism of the God-Man to the feudalistic warrior culture of the early Middle Ages.

Chickering:

Now, against Grendel, alone, I shall settle

this matter, pay back this giant demon.

I ask you now, protector of Scyldings,

king of the Bright-Danes, a single favor—

that you not refuse me, having come this far,

guardian of warriors, friend of the nations,

that I be allowed to cleanse great Heorot,

alone, with my men, my noble warriors.This is another fine rendering from Chickering, though Beowulf’s reference to “a thing with the thyrs”—and therefore the implications of his ironic discourse—is lost.

Heaney:

Now I mean to be a match for Grendel,

settle the outcome in a single combat.

And so, my request, O king of Bright-Danes,

dear prince of the Shieldings, friend of the people

and their ring of defense, my one request

is that you won’t refuse me, who have come this far,

the privilege of purifying Heorot,

with my own men to help me, and nobody else.I like Heaney’s use of “purifying” here, and the passage has a stately eloquence that seems fitting. Note, however, that the original contains a repetition that is characteristic of Old English poetic style: “with my band of warriors, / and this hardy troop.” Rather like biblical parallelism, this device conveys the same idea in different words, thus enriching the overall meaning. Heaney reduces this to simply “my own men.”

Mitchell:

Now I will go face Grendel alone

and pay him back for his brutal crimes.

Therefore, lord of the Scyldings, allow me

this one request—since I have come

from so far away, do not refuse me:

to rid your radiant house of this evil

without the help of my own men.Mitchell’s rendering again strikes me as overly modernized, with phrases like “his brutal crimes,” “from so far away,” and “radiant house” feeling stylistically out of place. Also, the original contains “a remarkable string of ruler-epithets … [that] provide a picture of idealized kingship” (Ramey, p. 48). I find it almost inexplicable that Mitchell would want to reduce all of this richness—“ruler of the Bright-Danes,” “shelter of the Scyldings,” “protector of warriors,” “friend of the people”—to one rather bland phrase: “lord of the Scyldings.”

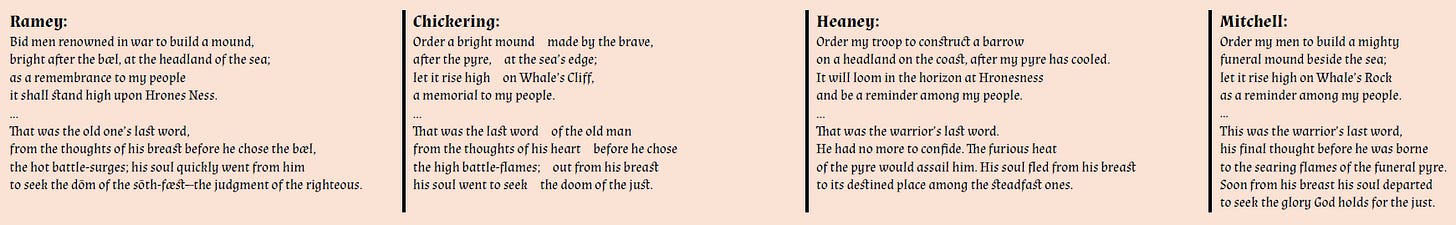

Passage 3: Lines 2802–2805, 2817–2820

Hātað heaðomǣre hlǣw gewyrcean

beorhtne æfter bǣle æt brimes nōsan;

sē scel tō gemyndum mīnum lēodum

hēah hlīfian on Hronesnæsse.

...

Þæt wæs þām gomelan gingæste word

brēostgehygdum, ǣr hē bǣl cure,

hāte heaðowylmas: him of hreðre gewāt

sāwol sēcean sōðfæstra dōm.Ramey:

Bid men renowned in war to build a mound,

bright after the bæl, at the headland of the sea;

as a remembrance to my people

it shall stand high upon Hrones Ness.

…

That was the old one’s last word,

from the thoughts of his breast before he chose the bæl,

the hot battle-surges; his soul quickly went from him

to seek the dōm of the sōth-fæst—the judgment of the righteous.bæl: fire, funeral pyre

dōm: glory; judgment

sōth-fæst: true, loyal, righteous

Tolkien called Beowulf a “heroic-elegiac poem”; this passage places us in the subdued elegy, gray-blue and lovely like a northern sea, of the poem’s final sections. Mortally wounded in his battle against the dragon, the hero orders that his burial mound be built at Hrones Ness (Whale’s Bluff), and then he follows his kinsmen into the afterlife.

In Tuesday’s post, I observed that modern words tend to be specific and clearly defined, whereas ancient words often possessed a complex network of meanings. The coexistence of many possible meanings in a single word is called polysemy, and Ramey comments on the evocative polysemy of the final line in this passage: “The straightforward interpretation of this sentence is that Beowulf’s soul went to heaven. But the poet leaves some ambiguity, no doubt intentionally. Dōm can mean ‘judgment’ as well as ‘heroic glory,’ a rich polysemy that allows the poet to meld the heroic and heavenly dōm, even implying that one can lead to the other” (p. 152). Thus, this crucial moment in the story deepens and accentuates, through expansive language, one of the poem’s fundamental themes: “The poet’s theological project … is to build a bridge with the heroic pagan past, recuperating the heroic legends and enfolding them within a Christian vision” (p. 60).

Chickering:

Order a bright mound made by the brave,

after the pyre, at the sea’s edge;

let it rise high on Whale’s Cliff,

a memorial to my people.

...

That was the last word of the old man

from the thoughts of his heart before he chose

the high battle-flames; out from his breast

his soul went to seek the doom of the just. I have mixed feelings about “the doom of the just.” The negative connotation of “doom” in modern English creates a thought-provoking paradox with “of the just,” but I’m not sure if that paradox is helpful here. In general, though, this is a skillful and vivid rendering that stays close to the original.

Heaney:

Order my troop to construct a barrow

on a headland on the coast, after my pyre has cooled.

It will loom in the horizon at Hronesness

and be a reminder among my people.

...

That was the warrior’s last word.

He had no more to confide. The furious heat

of the pyre would assail him. His soul fled from his breast

to its destined place among the steadfast ones.I’m not sure how to form a mental image of “loom in the horizon,” which distracts from the stark beauty of the Old English: “it shall … tower high on Hrones Ness.” Also, the term “reminder” seems like a weak, rather quotidian alternative to “remembrance” or “memorial.” On the other hand, I like Heaney’s elegant and subtly ambiguous rendering in the concluding line: “to its destined place among the steadfast ones.”

Mitchell:

Order my men to build a mighty

funeral mound beside the sea;

let it rise high on Whale’s Rock

as a reminder among my people.

...

This was the warrior’s last word,

his final thought before he was borne

to the searing flames of the funeral pyre.

Soon from his breast his soul departed

to seek the glory God holds for the just.Mitchell’s style is more pleasing in this passage, which has an air of poignant simplicity.

Both Heaney and Mitchell use “warrior” instead of “old man,” which seriously alters the mood surrounding Beowulf’s death. I don’t know why they did this, since the Old English word—gomelan, from the adjective gomel—means “one who is advanced in age.” Mitchell also inserts “God” in the final line; this departs boldly from the poetry and the theological nuance of the original.

I hope this exploration of Beowulf translations has been helpful for you. In Tuesday’s post for paid subscribers, which may be delayed if the approaching ice storm causes power or Internet outages, I’ll conclude this Beowulf series with some reflections on the poem’s cultural milieu. I argued that literary works like Beowulf are not “primitive,” but what about Anglo-Saxon England more generally—was this a “primitive” culture?

Thank you for this insightful comparison of translations. I wonder if you've seen the recent translation by Tom Shippey (with a commentary by Leonard Neidorf). Here's 74 - 85:

I heard that across middle-earth there were many tribes

set to work, to make splendid the great seat of the people.

It happened quickly as time goes among men,

that it was all ready, the greatest of halls.

He whose word ruled widely gave it the name

of Heorot, Staghall. Nor did he belie his word,

he gave out rings and treasure at the feast.

The hall towered, high and wide-gabled.

It was waiting for the fire of war, hateful flame —

after deadly spite, the armed hatred

between father and daughter's husband.

In general, I've been enjoying it as a plain and clear, if not very poetical, rendering, one that frequently includes helpful explanatory glosses of names (as with "Staghall," here). But I'd be interested in the impressions of someone with your superior knowledge of the poem.

I am just curious: which translation do you consider the most poetic? And which one, in your opinion, is the most accurate? (By the way, it seems common for the best part of any translation to be found in its... notes—such as in the case of the word 'fælsian.' :) ) Benjamin Bagby's performance is wonderful!