Book Review: The Word-Hoard Beowulf, by Peter Ramey

Ramey combines a fascinating introduction and excellent notes with a sui generis approach to translating Old English.

What exactly is the greatness of Beowulf? I still find this question difficult to answer. The overarching structure and style of the narrative, as we discussed last week, contrast rather violently with the meticulously crafted plots, verisimilar action, and “round” characters that we find in the works of Jane Austen, George Eliot, Anne Brontë, and other great novelists of the nineteenth century. Furthermore, the poetic qualities of its alliterative verse are largely lost in translation, and even in the original language, Beowulf is a long poem that doesn’t possess the artistic coherence and expressive density of shorter poems such as “The Wanderer” or “The Dream of the Rood.” Even the strange monsters and heroic feats are of limited value, insofar as those elements of the story are nowadays widely available elsewhere, and in forms that many modern readers would prefer.

Does the greatness reside, then, in Beowulf’s towering position and seminal status in the history of English letters? Well, not really, because its influence on subsequent works of literature is much more subdued than one might expect. Older texts do not allude to it, and it was virtually unknown during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when English was maturing into a modern literary language. Long confined to a sole surviving manuscript, Beowulf was not printed until 1815—about a thousand years after it was written.1 Its reputation for literary excellence came even later and owed much to the efforts of a certain J. R. R. Tolkien, who published “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” in 1936. Finally, it was not until Edwin Morgan’s 1952 translation that the poem was fully integrated into the aesthetic cosmos of modern English.

Surely, then, the greatness is to be found in Beowulf’s stirring evocations of English culture and history. Isn’t it, after all, the patriarchal English epic, like the Song of Roland for France and the Song of My Cid for Spain? Again, not really. It doesn’t take place in England, makes no reference to the British Isles, and includes not one Englishman.2

And yet, Beowulf has been thoroughly integrated into popular culture, taught by countless professors, read by countless students, translated hundreds of times into many languages, and placed upon a lofty and seemingly immoveable throne in the canon of British literature. There is a hint of irreducible complexity in the way that certain literary texts (and not others) kindle the imagination and elicit widespread admiration; I have no intention of presenting Beowulf’s greatness as simple when it is, in reality, quite complex. Nevertheless, I’ll propose something that does, I believe, cut to the quick of this very old poem’s mysterious and, I might even say, very modern power. The magic of Beowulf is a matter of tone—that is, of a poetic tonality whose shades of sincerity and seriousness and unaffected conviction form a deeply appealing contrast with a fantastical, mythical, even surreal story. Reading Beowulf is like contemplating the world with the mind of an adult and the eyes of a child—which is rather like something that another ancient Poet, speaking with utmost gravity, insisted that we do:

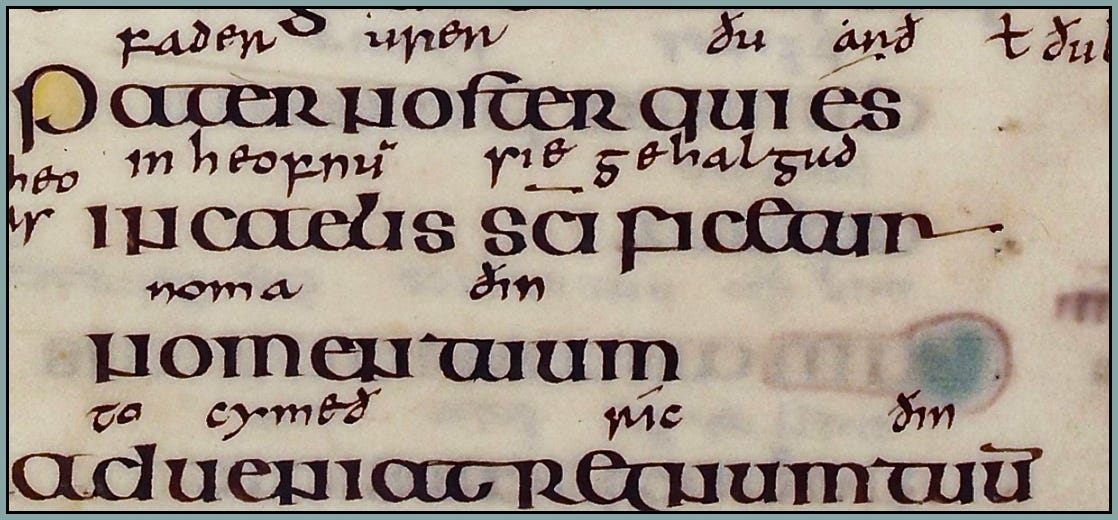

Soðlice ic secge eow, buton ge beon gecyrrede & gewordene swa swa lytlingas, ne ga ge on heofena rice.

(Truly I say to you, except ye turn and become as little children, ye go not into the kingdom of heaven.)

The Word-Hoard Beowulf, an annotated translation by Professor Peter Ramey of Northern State University, was published by Angelico Press in 2023.

I mentioned above that translations of Beowulf are not at all in short supply, so we must first address the perfectly legitimate question of why yet another attempt is called for. Ramey himself provides the answer:

Apart from the Bible, Beowulf may well be the text most translated into modern English. There are rhyming Beowulfs, prose Beowulfs, experimental Beowulfs, feminist Beowulfs, graphic-novel Beowulfs, and nearly every other kind of Beowulf conceivable. But none of them affords access to the rich and multilayered vocabulary of the original.3

As the book’s title suggests, the poetic element at the center of this translation is words, and more specifically, words in the fullness of their power to draw our hearts and minds into the mystical depths of an imagined world. Ramey explains that in Tolkien’s theory of language, words are much more than a means of conveying information and provoking emotional responses. In their polyvalent, sometimes paradoxical, layers of signification and association and etymological growth, words are actually “carriers of culture” and “the repository of myth”:

For Tolkien, the belief systems and stories of a culture are embedded in its words. Because, as Tolkien maintains, “the incarnate mind, the tongue, and the tale are … coeval,” thought, language, and belief interpenetrate one another. Words encode particular ways of seeing…. The same linguistic principle lies at the root of Tolkien’s own mythmaking, which begins with the invention of his own languages and from there grows into narrative.4

If you’ve sampled modern Beowulf translations, perhaps you’ve noticed some of the disappointments and deficiencies that Ramey resolved to overcome: the poem’s religious resonance is muted, its metaphysical landscape is flattened, its mythical artistry is distorted, and its theological richness is buried under the artificial turf of a prosaic, de-spiritualized society in which Beowulf’s runic and Christian and wondrously medieval world “often comes out looking like a comic book.”5 My friends, this is not to be borne! Literature is an irreplaceable window into the poetic mentality and incarnational spirituality of the Middle Ages, and Beowulf is the only surviving long epic poem from early-medieval England. We must strive to experience it as the “vast cosmological drama”6 that it is!

Sadly, the full effect is unattainable.7 As Ramey points out, “modern English has nothing like the Old English poetic vocabulary”8 from which the poem’s textual world was wove: modernity stands face to face with Beowulf’s verbal art and is, in a certain sense, speechless.

But improvement is possible. We must seek to do our part, and in the meantime, we should be grateful to Dr. Ramey, for he has already done his part.

I will conclude this review by discussing the translation philosophy of The Word-Hoard Beowulf and summarizing the book’s virtues. In Tuesday’s post for paid subscribers, I’ll share some memorable passages from Ramey’s rendition of the poem, and with help from his scholarship, we’ll look more deeply into the linguistic and spiritual richness of Beowulf.

Ramey has found that “the limitations of modern English are especially problematic for representing metaphysical and mythical elements.” Thus, he adopts a radical strategy. In an attempt to “bridge the gulf between specialists and non-specialists,” he gives all readers partial access to Beowulf’s captivating treasury of words, thus seeking to draw us into “a poem of unfathomable depths.”9

This is accomplished, first of all, by integrating key Old English terms into the modern English text. These terms are explained in footnotes and defined in a glossary. Your objective, as the reader, is to gradually acquire an intuitive sense and deep appreciation for the meanings and expressive potential of these words, which have no adequate equivalent in modern English. Examples of the words that Ramey retains from the Old English are thrym (power, force, greatness, glory), drēam (communal joy, the festive bliss of the hall), frōd (wise and old, and therefore wise because of being old), theod (nation, tribe, people group, troop of warriors), and sibb (kinship, friendship, peace).

It is undeniable that Ramey’s bold approach places additional burdens on the reader, initially impedes comprehension, and has a “foreignizing” effect that some might find distasteful. My response is simply this: it’s worth it. We’re talking about Beowulf here, a one-of-a-kind text that deserves to be pondered, savored, and studied, not merely read. The unfamiliar words will slow you down, but I don’t see much point in “finishing” the poem anyway, because once you’re done, you’re fresh out of full-length Anglo-Saxon epics. Reaching the end is merely the prelude to re-reading, and each time you re-read, the Old English words—and along with them, the enjoyment, the comprehension, the poetic transformation—will sink deeper into your soul.

Apart from the technique of integrating key words from the original text, Ramey’s rendering is just what it should be: “a literal, line-by-line representation of the Old English”10 that welcomes alliterations when they come naturally but doesn’t go out searching for them. Though I frequently depart from literalism in my translations of poetry, and in many cases even consider such departures obligatory, the literal approach is eminently appropriate for a poem like Beowulf.

The Word-Hoard Beowulf includes an abundance of edifying, insightful footnotes that are informed by Ramey’s robust scholarship and his understanding of Beowulf as a thoroughly Christian poem. There are also explanatory glosses in the margin and helpful summaries of the poem’s prologue and forty-three sections (called “fitts”). The book thus has all the resources that a typical reader will need, and I am happy to recommend it as an affordable, comfortably sized, visually pleasing, and poetically unique edition of a timeless classic which is, as Tolkien said, “written in a language that after many centuries has still essential kinship with our own”:

“it was made in this land, and moves in our northern world beneath our northern sky, and for those who are native to that tongue and land, it must ever call with a profound appeal—until the dragon comes.”

Estimates for the date of Beowulf’s composition extend from the seventh century to the eleventh century. The eighth century seems most likely to me.

Furthermore, according to Tolkien, “Beowulf is not an ‘epic’…. No terms borrowed from Greek or other literatures exactly fit: there is no reason why they should. Though if we must have a term, we should choose rather ‘elegy.’ It is an heroic-elegiac poem.” I nonetheless call it an epic for the sake of convenience, and because the term is sufficiently apt if understood broadly.

“Introduction,” p. 15.

“Introduction,” p. 5.

Ibid.

Ibid.

The possible exceptions are the few specialists out there who can fluently read untranslated Anglo-Saxon poetry (by no means an easy task!), but even they are limited by our imperfect knowledge of Old English as a living language in which ordinary people communicated.

“Introduction,” p. 4.

“Introduction,” p. 16.

“Introduction,” p. 18.

Quote:

"As Ramey points out, 'modern English has nothing like the Old English poetic vocabulary' from which the poem’s textual world was woven: modernity stands face to face with Beowulf’s verbal art and is, in a certain sense, speechless."

I think this kind of realization is inevitable every time we confront the mentality and languages of the modern world with the poetic vocabulary and vision of classical, ancient worlds. But, at the same time, I think that this is applicable in the case of any translation of a poem. Poetry proves the famous old adage "Traduttore, traditore." Poetic creations are exceptionally conditioned by the outer and inner music of the specific language in which the poem has been written. Essentially, and in most cases unconsciously, every poem is an attempt to rediscover the beauty of the language of Paradise. Of course, all these attempts are destined for failure—and there is no great poet who has not understood this in one way or another. [That is why one of the greatest Romanian poets, Tudor Arghezi (1880–1967; nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1965), considered himself a perennial debutant until the end of his life.] This does not mean that poetry should not be written or that translations are not worth the effort: on the contrary, they are the most beneficial and significant intellectual and spiritual efforts of a culture.

Therefore, any such effort is worth welcoming and encouraging—and the younger generations must be guided to love and value poetry much more than any other type of creation. Not just poetry in general, but sacred poetry, like the Psalms written by King David, in particular. And then epic and heroic poetry—such as Beowulf—in particular.

Personally, I warmly congratulate both the author of this article, Robert Keim, and the remarkable translator of Beowulf, Peter Ramey. I can’t wait to receive and read this remarkable achievement!

If possible, I would be very glad to read an article that comparatively discusses all the existing translations of Beowulf (and I would also appreciate the mention of all those editions that are bilingual—with parallel texts in Anglo-Saxon and English).