Beowulf and the Myth of “Primitive” Literature

Medieval poetry is a bridge to the sacred past (and there is such a thing as too much Jane Austen).

Let’s begin with a brief comparison:

Mr. Bingley was good-looking and gentlemanlike: he had a pleasant countenance, and easy, unaffected manners. His sisters were fine women, with an air of decided fashion. His brother-in-law, Mr. Hurst, merely looked the gentleman; but his friend Mr. Darcy soon drew the attention of the room by his fine, tall person, handsome features, noble mien, and the report, which was in general circulation within five minutes after his entrance, of his having ten thousand a year. The gentlemen pronounced him to be a fine figure of a man, the ladies declared he was much handsomer than Mr. Bingley, and he was looked at with great admiration for about half the evening, till his manners gave a disgust which turned the tide of his popularity; for he was discovered to be proud.

Thus does Jane Austen begin to weave two principal characters into one of her most famous stories.

Below is a passage in which an author begins to weave a principal character into a prose narrative that is even more famous than Pride and Prejudice.

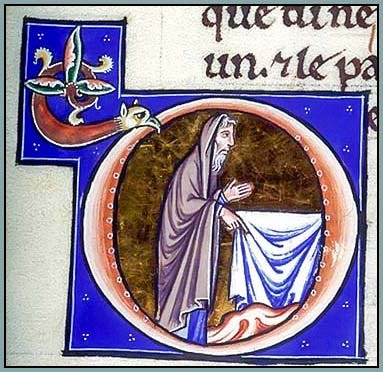

And YHWH says to Abram, “Go for yourself, from your land, and from your family, and from the house of your father, to the land which I show you. And I make you become a great nation, and bless you, and make your name great; and be a blessing. And I bless those blessing you, and I curse him who is cursing you, and all families of the ground have been blessed in you.” And Abram goes on, as YHWH has spoken to him, and Lot goes with him, and Abram [is] a son of seventy-five years in his going out from Haran. And Abram takes his wife Sarai, and his brother’s son Lot, and all their substance that they have gained, and the persons that they have obtained in Haran; and they go out to go toward the land of Canaan; and they come to the land of Canaan. And Abram passes over into the land, to the place of Shechem, to the oak of Moreh; and the Canaanite [is] then in the land. And YHWH appears to Abram and says, “To your seed I give this land”; and there he builds an altar to YHWH, who has appeared to him.

These are the opening verses of the twelfth chapter of Genesis in the Literal Standard Version, which preserves literary qualities that fade from view in the idiomatic English Bibles that most people read (the best of which are, nonetheless, far preferable to “literal” translations for most purposes).

The stylistic difference between these two passages is immense. Jane Austen is arguably the preeminent stylist in the history of English-language prose narrative: she structures her paragraphs, molds her sentences, and chooses her words with such consummate skill—such elegant balance of force and complexity, such engaging interplay of sincerity and irony—that real life would presumably be much better if she were narrating it to us.

The literary style of Genesis, in comparison, might be perceived as downright “primitive”:

The story begins abruptly and lacks a witty or dramatic lead-in to pique the reader’s interest;

a major character is identified as the unpronounceable “YHWH”;

the verb tenses don’t feel quite right;

key lexemes (“bless,” “great,” “go,” “land”) are used in a noticeably repetitive way;1

Abram’s descendants are described, rather strangely, as his “seed”;

information (such as Abram’s age) is inserted where we wouldn’t expect it;

other information (YHWH’s appearance to Abram) is mentioned twice in the same sentence;

and the entire passage is highly paratactic. Parataxis is narration in which the thoughts are more self-contained and seem to be “in parallel”: And YHWH says to Abram, … and Abram goes on, … and Lot goes with him, … and Abram takes his wife Sarai, … and Abram passes over into the land…. Elegant modern prose, in contrast, favors hypotaxis, in which thoughts are made subordinate to other thoughts, such that ideas become more interrelated and sentences more complex. I’ll provide a fine example of Austenian hypotaxis in a footnote.2

It would seem, then, that from a stylistic perspective, Genesis can’t compete with the nineteenth-century novels that have so powerfully shaped the modern literary experience. And we’ve looked only at one short passage—if we analyzed an entire narrative from the Old Testament, we could also find “faults” occurring at the higher levels of character development or plot structure.

And yet, scriptural narratives were kindling emotions and delighting the intellect and exciting the imagination well into the modern era. Also, for those who accept the doctrine of biblical inspiration, those narratives were written in collaboration with Almighty God, who authored an entire universe with perfections and complexities that utterly surpass the workings of the human mind. Thus, there must be something more to the story of “primitive” literature.

As I mentioned in the subtitle of this essay, there is such a thing as too much Jane Austen (or too much Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Charlotte Brontë, etc.). I could cite a few reasons for this, but here I’m concerned with one that is generally overlooked, and which is also crucial to the survival of Western Civilization. (Okay, maybe that’s a bit of hyperbole. Maybe.)

The problem is that these books have a tendency to do precisely what we observed in the preceding discussion: they make Sacred Scripture—and to a lesser extent, other ancient masterpieces such as the Odyssey and the Aeneid—appear rough, rudimentary, unrefined: in a word, primitive. Furthermore, they may shape our aesthetic sensibilities in such a way as to distance us, emotionally, intellectually, and artistically, from the Bible.

If you regard the Bible as the fundamental sacred text upon which your religion, and therefore your entire worldview, is built, I don’t need to convince you that such distancing is a danger to happiness in this life and the next. But this danger extends beyond the individual believer to society as a whole, because no other book—no other artistic creation of any kind—has so powerfully and thoroughly and profoundly shaped the culture and collective consciousness of the West. Let’s recall the quotation that we explored in the Age of Angels series: “For medieval Christians, Scripture was the primary source for understanding their own world.” And when we say “medieval Christians,” we are referring to a one-thousand-year period during which Christian communities sent deep roots into the eroding soil of Antiquity and grew, slowly but steadily, into a civilizational Tree of Life whose immensity and diversity are beyond all measure, and whose cultural achievements are still the admiration of the world.

Tzvetan Todorov (d. 2017) was an influential and uncommonly insightful Bulgarian-French literary philosopher. In his book Poetique de la prose, he questions the very notion of “primitive” narrative (le récit primitif). At the moment, I have access only to the French version (an English translation is available if you’re interested), so the quotations below are translations that I made somewhat hastily for the purposes of this article.

The image of primitive narrative is … implicit as much in judgments about current literature as in certain scholarly remarks about the works of the [ancient] past.

The basic idea is that the modern mind sees literary narrative as primitive when it’s different in certain ways from modern literary narrative, which (more or less by definition) is “non-primitive.” The point here is not to blindly equalize all works of literature in a futile attempt to claim that no poem is really better than another, or that some third-rate epic written by a hack in Classical Greece is on the same artistic plane as Jane Eyre. The point is that an ancient narrative can be an enjoyable, finely crafted, enlightening masterpiece even when it feels very different from a modern novel, and even when it doesn’t obey the unwritten rules that modern readers impose on it. These rules, according to Todorov, are primarily

the law of plausibility: “all the words and actions of a character must agree with one another in terms of psychological plausibility—as if people of all eras consider the same combination of qualities to be plausible”;

the law of stylistic unity: “low and high style cannot be mingled”;

the law of non-contradiction: if two portions of a narrative are inconsistent or too paradoxical, something’s wrong;

the law of non-repetition: “there are no repetitions in an authentic text”; and

the law of non-digression: good authors don’t digress from “the principal action” of the narrative.

If these criteria are applied, “primitive” narratives (such as those of the Bible) will be found faulty indeed. But that’s the point: the criteria are a modern artifact. They reflect the thought patterns, lifestyles, and aesthetic values of modern society. If Holy Scripture—that is, the collected stories, poems, orations, epistles, and dream-visions of Almighty God—is to transform us, we must learn to read it on its own terms.

Furthermore, you might have noticed that these laws are not specific to literary narratives. In fact, they sound very much like the general “laws” that an egocentric (#1), overly analytical (#2), rationalistic (#3), prosaic (#4), hyperspecialized (#5) modernity would seek to impose on the grand and mysterious and beautifully nonlinear narrative that we call human life. And medieval culture—naturally, joyfully, passionately—contravenes them all:

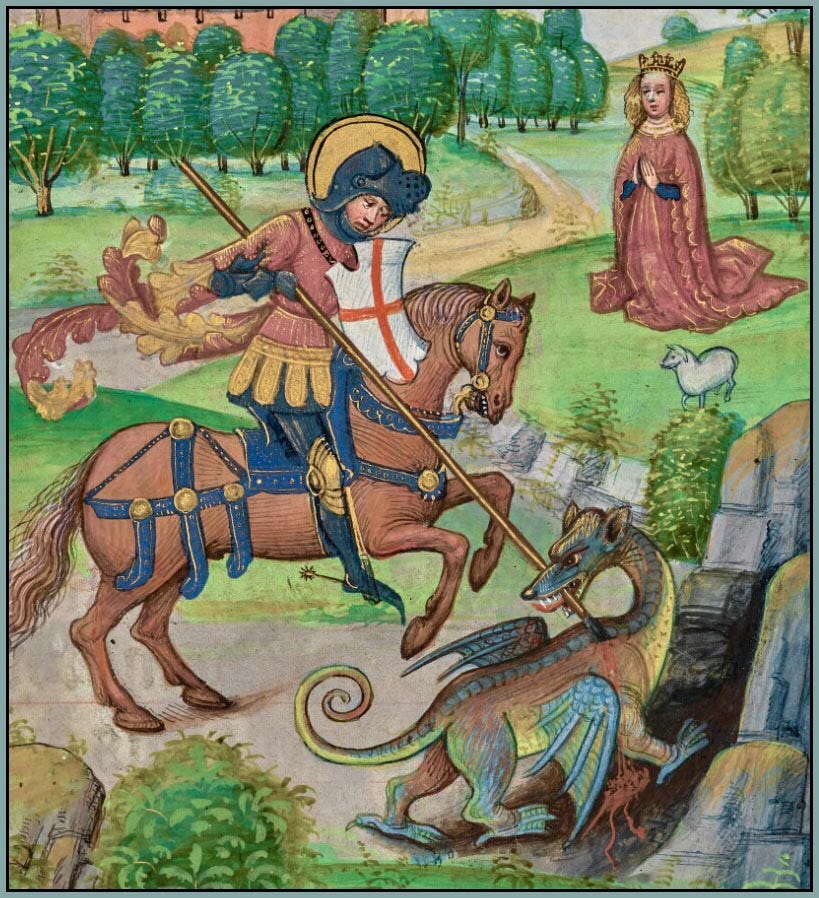

We pondered the ability of medieval noblemen to be simultaneously devoted Christians and fierce warriors.

We’ve seen illuminated manuscripts in which “chimeras, fantastical forms, and comical scenes” surround sacred texts, or in which a fairy-tale ivory castle coexists with a “wardrobe malfunction.”

We explored paradox as a foundational aspect of medieval life and a key to understanding medieval monasticism.

My colleague

has written and spoken about the importance of repetition in the liturgical rites that animated, inspired, and united medieval civilization.Medieval poetry is not afraid of stories that wander off the beaten path from time to time, and one medieval poem is particularly famous for its digressions. That poem is the one mentioned in the title of this article—phew, we’ve finally made it to Beowulf.

Actually, I don’t have much more to say about Beowulf right now. The fundamental point I want to make is that modern literature shapes us in its own image, such that ancient literature, and especially biblical literature, may not resonate in our hearts and minds as powerfully and harmoniously as it should. Perhaps you have noticed this lack of resonance in your relationship, or in your children’s or students’ relationship, with Scripture. Indeed, I would not be surprised to find that the experience is, nowadays, nearly universal.

What can be done? By no means should we stop reading good modern literature. What we need, instead, is more literature, but of a different kind. We need a via media—something that blends modern and ancient modes of expression. The via media I recommend, as you might have guessed, is the via mediaevalis. Medieval poetry can sensitize us to the literary aesthetics of Holy Scripture, and one of the best medieval poems available to us is Beowulf.

The post on Tuesday will be Christmas-themed. We will resume this topic next Sunday, with a book review. The book is a new translation, with an introduction and commentary, of Beowulf. Many translations of Beowulf have been made, but this one is in a class of its own.

To speak of a lexeme is to speak of one root word that appears in various grammatical forms. Bless, blesses, blessed, and blessing, for example, are different words, but they still can make a text sound unpleasantly repetitious because they all emerge from the lexeme bless.

“One morning, about a week after Bingley’s engagement with Jane had been formed, as he and the females of the family were sitting together in the dining-room, their attention was suddenly drawn to the window by the sound of a carriage; and they perceived a chaise and four driving up the lawn. It was too early in the morning for visitors; and besides, the equipage did not answer to that of any of their neighbours. The horses were post; and neither the carriage, nor the livery of the servant who preceded it, were familiar to them. As it was certain, however, that somebody was coming, Bingley instantly prevailed on Miss Bennet to avoid the confinement of such an intrusion, and walk away with him into the shrubbery. They both set off; and the conjectures of the remaining three continued, though with little satisfaction, till the door was thrown open, and their visitor entered. It was Lady Catherine de Bourgh.”

I agree with much of what you say here. But there are no digressions in Beowulf. I love Jane Austen, but her range is limited, and she only touches lightly upon the very deepest wellsprings of human good and evil. She did not intend to do otherwise. My study of medieval literature and of classical epic and drama shows instead that these works are far more complex than modern novels are, and that we are hard put to read them as they were intended to be read. So when I say that there are no digressions in Beowulf, I mean that the poet has woven together a vast tapestry of motifs that are to be heard as it were simultaneously, each reflecting upon the others as they accrue meanings and associations while we move through the poem. The fight at Finnsburgh is crucial to the whole. Modern novelists do not work that way. Dickens did -- but most people, I find, do not understand what he was doing.

An interesting direction for reflection could be the following: What qualities do avid readers possess that allow them to read with great joy both the "primitive" texts of the Holy Scripture and modern authors like Jane Austen, T.S. Eliot, or E. Hemingway? Anyway, as far as I'm concerned, I've noticed that most "elitists" who consider sacred texts "primitive" hold radical aesthetic opinions that not only ignore Aristotle's classical theories expounded in "Poetics," but also exclude entire types and literary genres that do not conform to their aesthetic "canon." Additionally, I've noticed something else: most of the time, they do not read "fairy stories," myths, and legends. Therefore, they not only exclude authors like Tolkien and Lewis but also consider fairy-tale readers "primitive." If you ask me what is lacking in their case, I would respond: the spirit (i.e., the innocence) of childhood.