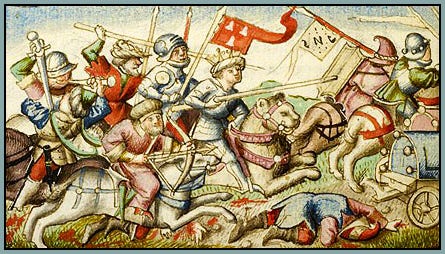

Consider the following illumination from a fourteenth-century Italian manuscript:

The people depicted here are the Maccabees, a group of Jewish insurgents who gained control of Judea at a time when it was ruled by foreigners. In the Middle Ages, the Maccabees were seen as symbolic forerunners of the Crusaders, who also fought to gain control of Judea, which had become a sacred place for Christians as well. The problem is that the Maccabees, despite being Middle Eastern warriors who lived in the second century BC, look very much like European knights of the fourteenth century AD.

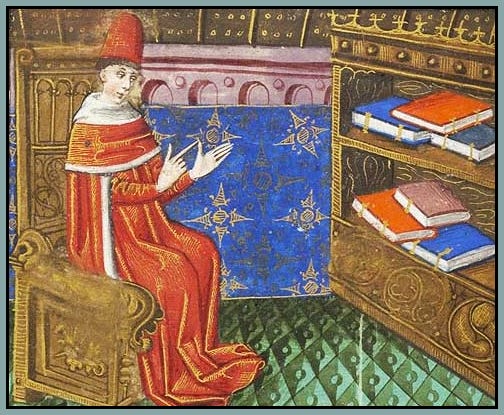

And then we have this, painted about a hundred years later:

The artist is showing us Alexander the Great fighting against Darius III. That happened in the fourth century BC. Once again, the battle looks strangely medieval.

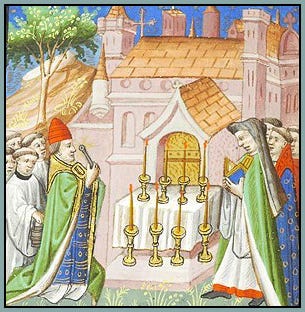

While we’re talking about Alexander the Great, let’s have a look at his teacher, Aristotle:

He is sitting on a medieval throne wearing medieval attire, and those books on the shelves look much more like medieval codices than Hellenic scrolls.

Let’s try a female historical figure, to see if we can find a representation that’s a bit more realistic:

No luck. That delightfully medieval queen is actually Queen Hecuba, wife of King Priam, the man who ruled Troy during the Trojan War.

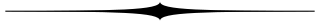

Let’s look at one more example, my favorite thus far:

The scene in question is the dedication of the Temple built by King Solomon, circa 950 BC. The Jewish high priest is a Christian bishop, his Jewish assistants are tonsured Christian clerics, and the Jewish Temple is a Romanesque church.

It would be easy to make light of the way that medieval artists transpose all the people and events of the past into the culture of their own era. We could dismiss it as ignorance, or self-importance, or even cultural appropriation, and perhaps those things did play a part. But I propose that there’s something far more significant going on here. What we really see in these images is the “eternalization” of human history. In other words, what we see is the absence of time.

Over the last couple weeks, we’ve discussed poetic time, linear time, cyclical time, and medieval time, which combines all three. The phenomenon we’re studying today is still medieval, but we can’t call it medieval time, because the whole point is that in medieval culture, time had a strange tendency to dissolve into something resembling eternity. The topic today is non-time.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Via Mediaevalis to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.