Time in the Via Media

Medieval life: a journey through cycles to the heavenly city

After exploring the medieval monastery as a place where the passage of time was poetic and cosmological rather than mechanical, we discussed historical time as a linear, “goal-oriented” phenomenon in modern culture and as a cyclical phenomenon in ancient culture. Now we will turn our attention to that inexhaustibly thought-provoking via media between Modernity and Antiquity—those ten centuries which appear to us as middle age in the life of Western man, and which we call the Middle Ages.

As one reader suggested in a comment on the previous post, “can linearity and cyclical interpretations of history both be correct”? Can we find in these two temporal modes not mere opposition but rather “an illuminating paradox”? Indeed we can—we need only look to medieval culture, which, as the eminent sociologist Pitirim Sorokin (1889–1968) recognized, was informed by the harmonious coexistence of cyclical time and linear time:

Summing up the main features of the Ideational medieval period, we see that the eschatological (with the two “terminal perfect points”) conception and the cyclical or endlessly undulating conceptions occupied the field.1

Let’s decompress this crucial passage:

When Sorokin describes the medieval period as “ideational,” he means that its cultural mentality was predominantly mystical, with trust placed more in faith and authority than in natural sciences and empirical observations. An ideational society naturally gravitates toward non-linear time—rather than waiting eagerly for scientific discoveries and technological advancements that the future will bring, it finds comfort in the eternal “now” of the spiritual realm, truth in the great thinkers of the past, and inspiration in the timeless heroes of history and legend.

Rather than the word “linear,” Sorokin uses “eschatological.” This is a more specific term for the historical model that St. Augustine, as explained in the previous post, saw as the inevitable response to Christian theology. Eschatology is the theology of final things—the end of each human life, the end of the entire world—and the two “terminal points” that Sorokin mentions are the beginning of mankind’s history (in the Garden of Eden) and the completion of mankind’s history (in the heavenly kingdom, after the Last Judgment). Medieval time was linear in this eschatological sense, because everyone from Piers the plowman to the Holy Roman Emperor saw their own individual life and all of human civilization as a one-way journey: life ends with death and judgment, followed by an eternal and irrevocable destiny in heaven or hell, and civilization ends with a new heaven and a new earth, when the Lord Christ returns in glory.

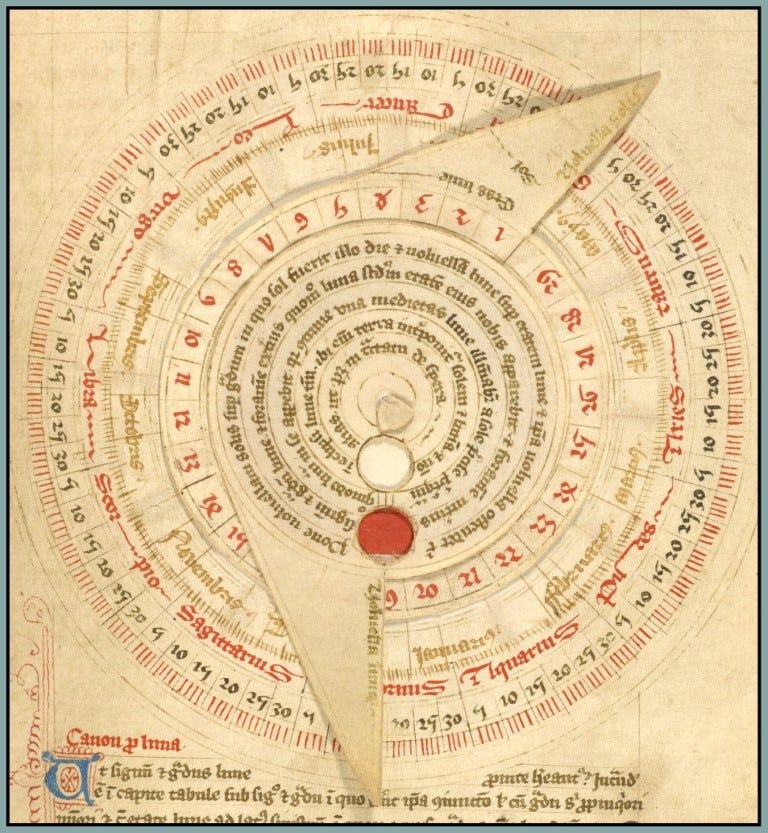

And yet, medieval culture blended this linear, eschatological vision with “cyclical or endlessly undulating” time. Why? Because the existence of medieval communities, the labors of medieval bodies, and the tapestry of thoughts in medieval minds resonated so deeply and so strongly with the cycles of Creation. Even St. Augustine saw it, and so did Peter Abelard, Roger Bacon, Robert Grosseteste, Albertus Magnus, Dante, Thomas Aquinas, and many others: the cycles of the natural world, particularly those of the heavenly cosmos, influence our lives as individuals and shape our history as a society. They are written in the very heart of human nature and in the very fabric of human civilization. They are part of us, and we are part of them.

That is the medieval answer to historical time, and to mankind’s place within it. That is the crux, the reconciliation, the balancing point, the divine union where, as the psalmist says, “justice and peace have kissed.” We can find peace in this world, made for us and redeemed for us, endowed with balance and cyclical order and elegant motions, filled with things old and ever new, always going yet always returning, illumined by stars that paint pictures in the sky, and by a sun that will undoubtedly rise, no matter how dark and desperate life appeared when it set.

And there will be justice at the end, when death has come upon us, when judgment is proclaimed, when “the first heaven and the first earth are passed away, and there is no more sea.” There will be justice, which is not synonymous with “punishment” but means proportion, equity, recompense—the restoration of harmony. It will include punishment, but only for those who deserve it. And it will include great gifts as well:

And He shall wipe away all tears from their eyes: and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, neither crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the first things are passed.

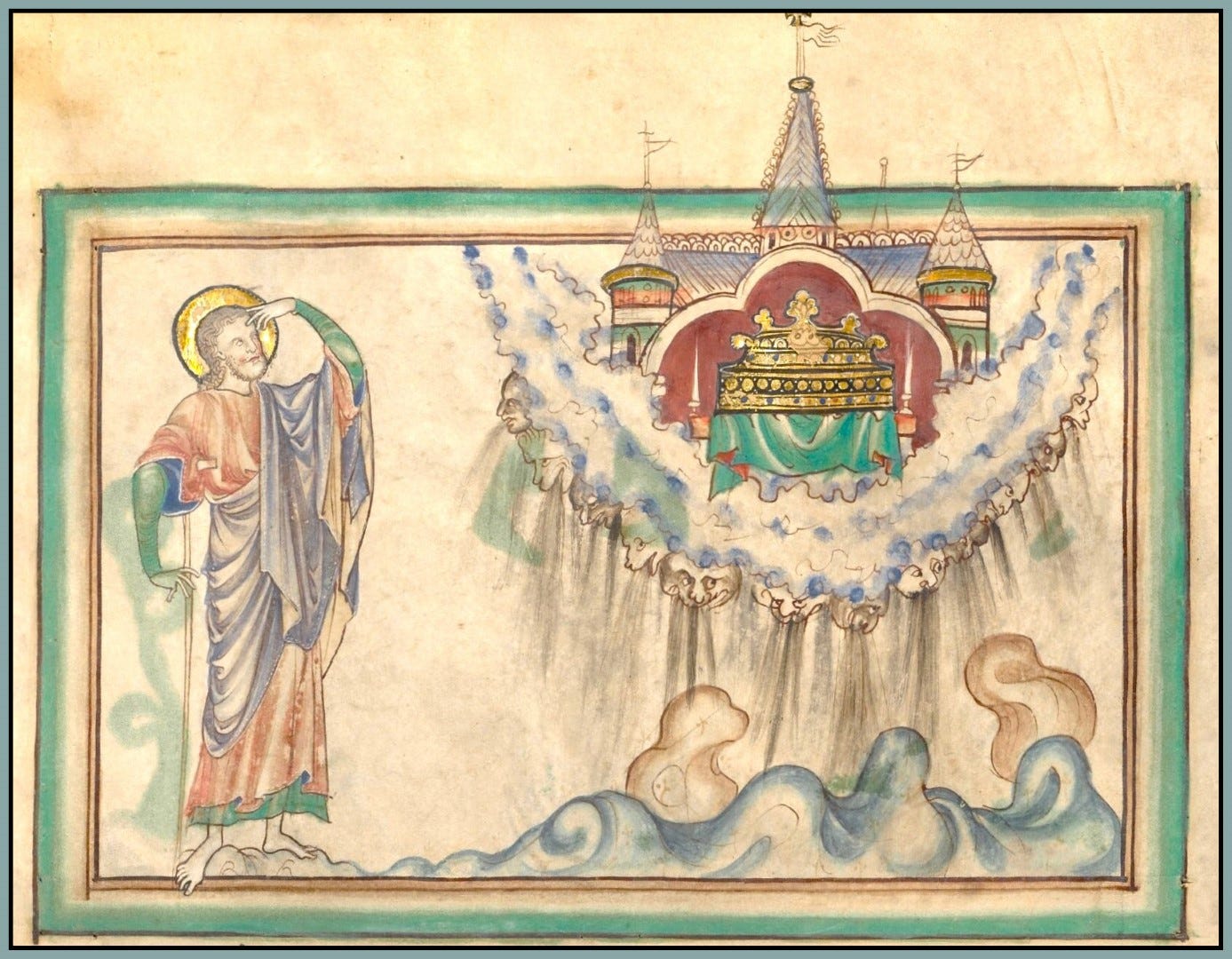

And yet even the end is not the end, for after the great cities of men have perished, after all things of the world are passed away,

I saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, made ready as a bride adorned for her husband…. And he that sat upon the throne, said, Behold, I make all things new. And he said unto me, Write: for these words are faithful and true. And he said unto me, It is done, I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end.

Medieval society, then, was ever immersed in the epic journey of human life, accompanied by the irreversible march of time as it moved steadily from Eden, through the Incarnation and Redemption, to the heavenly city and the consummation of all things. And during this journey, it was ever immersed in Creation as it appeared to the senses: beautiful, rhythmical, sublimely cyclical, wondrously permanent compared to the brief, fragile lives of men and beasts.

There is, however, one more form of time that we discern in medieval culture, and this will be our topic of discussion on Tuesday. It is time as we would expect to find it in a culture that thinks often and deeply about the human spirit, which is immortal, and about the Creator, who utterly transcends time in His supreme perfection and immutability. This is time that isn’t really time at all, but rather a pale and mysterious reflection of God’s eternity.

Pitirim A. Sorokin, Social and Cultural Dynamics, vol. 2. American Book Company (1937), p. 372.