The essay that I posted on Tuesday of this week, entitled Why the Sky Is Blue, presents a renewed vision of earthly life: drawing upon medieval wisdom, it suggests that the world is first and foremost a symbolic masterpiece painted by the divine Artist, and that we should experience, contemplate, and love it as such. That essay is, I think, the most important Via Mediaevalis article that I’ve written thus far; we’ll be building upon it in today’s post, and I hope you can find time to read it if you haven’t already.

My mind is still pleasantly adrift in the symbolic sea that we’ve been exploring over the past couple weeks, and before we return to The Medieval Year and look at calendrical artwork for November, I’d like to ponder some symbols that we encounter in daily life and can more fully appreciate through literature. It will, of course, be generously illustrated with miniatures from medieval manuscripts, so I hope this will be an enjoyable and visually appealing post for the end of the work week. I also hope, however, that it will help us all to continue rediscovering the enchanting poetry and rich, uplifting symbology of the human experience.

This early-fifteenth-century illumination depicts Nimrod and some companions worshipping fire. Nimrod is described in the Book of Genesis as “a mighty hunter,” and tradition says that he instituted idolatrous practices. (If you’re wondering why biblical-era individuals in this painting are wearing medieval clothes, you may want to read this article.)

Nimrod’s fire-worshipping instincts speak to fire’s primal and extremely potent significance in human psychology. The mythological literature of the ancient Greeks presents fire as a symbol of that which is uniquely human. It was something that could be either immensely powerful and almost unstoppable or weak and easily snuffed out. Thus, fire was a paradox very much like the paradox of human nature—man, in the Greek mind, was an ambiguous creature: in some ways like the gods, in some ways like the beasts, and ever caught up in a dangerous and disorienting dance of joy and sorrow, pleasure and pain, life and death.

Grass, like fire, is a symbol of human mortality. In the spring it grows with such vibrancy and beauty, such vigor and delicacy and extraordinary abundance, and yet, when the hour has come and the scythe approaches, the end is swift, and the verdure is soon gone. This metaphorical relationship was a favorite conceit of the Psalmist:

As a shadow my days are stretched,

I wither away like grass;

but thou, O Lord, endurest forever,

and thy name to all generations.For he knoweth how we are made,

remembering that we are dust:

man—his days are like the grass,

as meadow flower he flourisheth;

a breeze shall stir him, and he is gone:

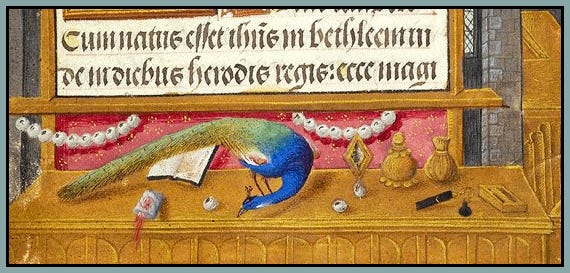

his place shall know him no more.Pearls held special significance in medieval culture, and their allegorical beauty was immortalized in the anonymous Middle English poem Pearl, a wonderful and moving text that is well worth reading. I recommend Brian Stone’s translation, and I will quote from his discussion of pearls and their symbolism:

Although other gems have had various symbolical associations in different cultures, the pearl, perhaps because of its whiteness, is almost constant in its representation of preciousness, purity, modesty, spiritual perfection. Indeed, its virtues seem curiously attuned to the spirituality of the Christian message, so that it became, in the Middle Ages, the characteristically Christian gem.

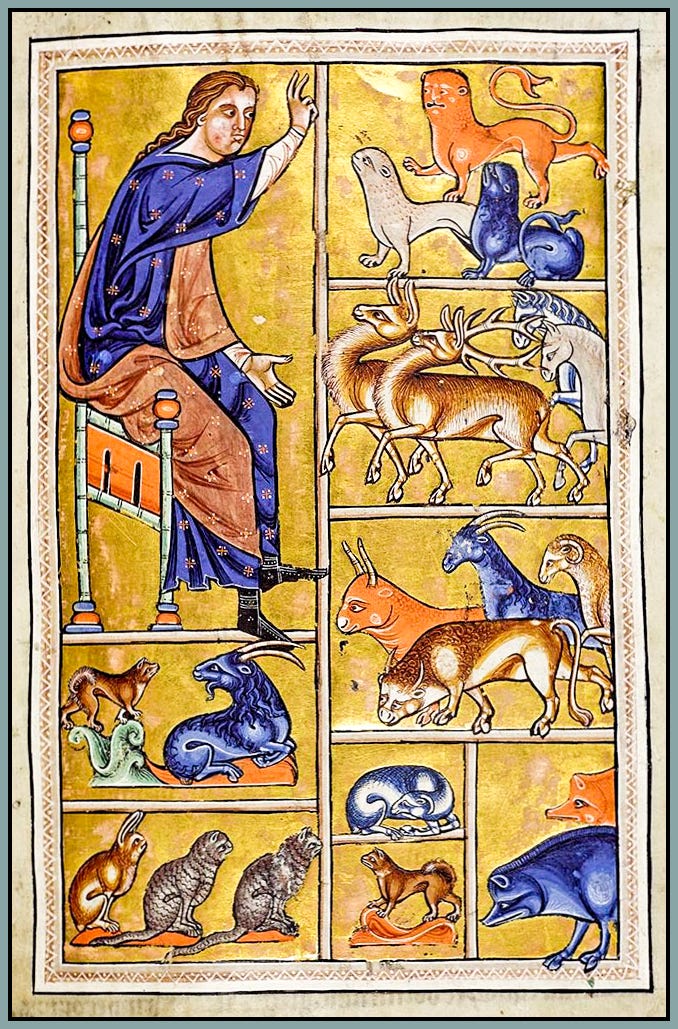

According to medieval bestiary lore, the swan signifies deception and mankind’s duplicity, because its white feathers conceal black skin. A Breton lay known as “Milun” tells the story of a knight and his (married) lover who communicate by attaching letters to a swan, with the first letter being hidden in the swan’s feathers. Perhaps Marie de France, the author of the poem, had some swan symbolism in mind when she crafted the story.

That which hath made them drunk hath made me bold.

What hath quenched them hath given me fire.

Hark!—Peace.

It was the owl that shrieked, the fatal bellman,

Which gives the stern’st good-night.

—Lady Macbeth

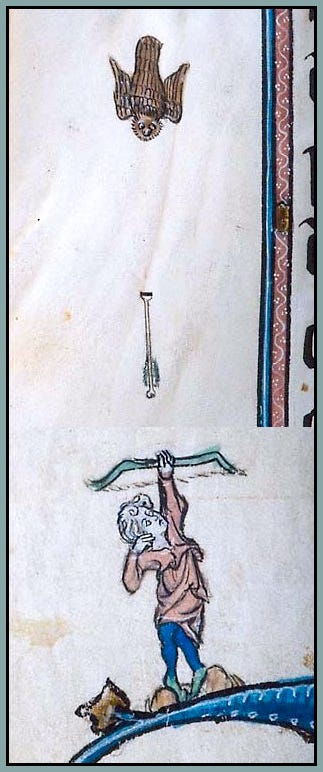

I’m sure that many medieval villagers were as intrigued and delighted as I am by the mystical call of an owl. Nonetheless, on the symbolic level, owls were generally bad news. They preferred darkness to light and therefore signified those who prefer to live in the darkness of sin. The owl also spent too much time around tombs, and, in Shakespeare’s memorable phrase, acted as a “fatal bellman”—because owls were wont to shriek when someone was about to die.

And yet, let’s not be hasty in scolding medieval folk for their fearful and superstitious tendencies. The Aberdeen Bestiary demonstrates that the harmonious and ever-insightful spirituality of the Middle Ages managed to discover the goodness of God even in the suspiciously nocturnal habits of the owl. Here’s the original Latin text, for those who enjoy that sort of thing:

Nicticorax Christum significat qui noctis tenebras amat, quia non vult mortem peccatoris sed ut convertatur et vivat. Ita enim deus pater dilexit mundum ut pro redemptione mundi morti traderet filium.

And now in English:

The night-owl signifies Christ. Christ loves the darkness of night because he does not want sinners—who are represented by darkness—to die but to be converted and live. For God the father so loved the world that he gave his son to death for the redemption of the world.