This is the fourth article in a series on medieval (and modern) marriage. The preceding articles are listed below.

To ensure coherency in our discussion of this important topic, today’s post was sent to all subscribers. Thus, paid subscribers will receive a third article later this week.

For what is wedlock forcèd but a hell,

An age of discord and continual strife?

Whereas the contrary bringeth bliss

And is a pattern of celestial peace.

These are the words of the Earl of Suffolk in Shakespeare’s 1 Henry VI, which takes place in the late Middle Ages. The earl seems to have internalized two features of Christian marriage that owe much to the work of medieval churchmen: first, that spouses should always exchange their vows voluntarily, and under no circumstances be compelled to marry; second, that marriage is a “pattern of celestial peace,” that is, an earthly reflection of lofty spiritual realities.

These are teachings that appeal strongly, I think, to most modern Christians. And yet, other aspects of medieval marriage, as we’ve seen in previous articles, do not appeal to modern sensibilities, and perhaps even strike us as seriously flawed. That these two things should coexist reminds us that marriage in medieval society was a multi-layered and somewhat mysterious facet of Christian life, and that’s why we’re trying to understand it and learn from it by thinking in terms of paradox. This article explores two aspects of paradoxicality, and we’ll conclude this discussion next Sunday with the central, and perhaps most illuminating, paradox of medieval marriage.

The various legal, psychological, and ethical ideas surrounding marriage have a remarkably complex history, even if we limit ourselves to the ancient and medieval cultures of western Europe. The fact is, there aren’t always simple answers when you’re dealing with relationships that involve emotions as powerful as love, and passions as fiery as sexuality, and social practices as crucial as raising children and forming alliances between families. A new layer of complexity arrives when you introduce Christianity, which blends pre-existing secular difficulties with a new vision of human morality, a uniquely mystical conception of the marital bond, and a deep-rooted ideal of consecrated virginity. Thus, one of the first things we should say in defense of medieval views on romance, matrimony, and conjugal pleasure is that human beings have been grappling with these issues for an awfully long time, and achieving the proper balance has never been an easy task.

Indeed, what modern society has attained is a very far cry from balance. If we look out at the world around us and consider the deplorable condition in which marriage now finds itself, we might wonder if the medieval approach had the effect of a bitter medicine: just as something that tastes painfully harsh may nonetheless safeguard the health of the body, so the harsh words of medieval saints may help to safeguard the institutional and moral health of marriage.

What I mean is that when it comes to love and sexuality, fallen human nature has such an overwhelming tendency toward excess and disorder that maintaining balance may actually require a certain degree of imbalance from society’s religious, intellectual, and political leaders. I’m not saying that medieval clerics and theologians were deliberately exaggerating their views in a calculated attempt to maintain the matrimonial order. What I’m proposing is that this relationship—balance achieved, paradoxically, through imbalance—is integral to the Christian paradigm of married life. We must acknowledge, for example, that a foundational text of the Christian religion, First Corinthians chapter 7, is reminiscent of the negativity and severity that we find in medieval writings:

“It is good for a man not to touch a woman.”

“I say to the unmarried and to the widows: It is good for them if they so continue, even as I.”

“But if they do not contain themselves, let them marry. For it is better to marry than to be burnt.”

“Art thou loosed from a wife? Seek not a wife.”

“If a virgin marry, she hath not sinned: nevertheless, such shall have tribulation of the flesh.”

“He that is without a wife is solicitous for the things that belong to the Lord: how he may please God. But he that is with a wife is solicitous for the things of the world: how he may please his wife. And he is divided.”

“If her husband die, she is at liberty. Let her marry to whom she will…. But more blessed shall she be, if she so remain.”

These words—still held as divinely inspired by Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestants—are woven into a discourse that is itself paradoxical, insofar as it seems to primarily discourage marriage while also encouraging it, and to primarily disparage marital sexuality while also esteeming it. Is this paradoxicality simply unavoidable, since Christianity is a religion that partakes so perfectly of earth and heaven, much as Jesus Christ partakes so perfectly of humanity and divinity, and given that marriage, as St. Thomas says, “signifies the conjunction of the two natures in the person of Christ”? If we perceive imbalances in medieval teaching on marriage, are these somehow inherent in the task of preventing serious imbalances in the lived reality of Christian matrimony, which is both a social institution and a sacrament, both a conjoining of souls and a uniting of bodies?

I think these questions are worth asking, but I affirm no answers, because the theoretical structure seems a bit wobbly. But theory need not completely eclipse practice; the (paradoxical?) reality is that the Middle Ages was an era in which marriage was subjected to much negativity from spiritual authorities, and it was also an era in which marriage was, on the practical level, absolutely flourishing.

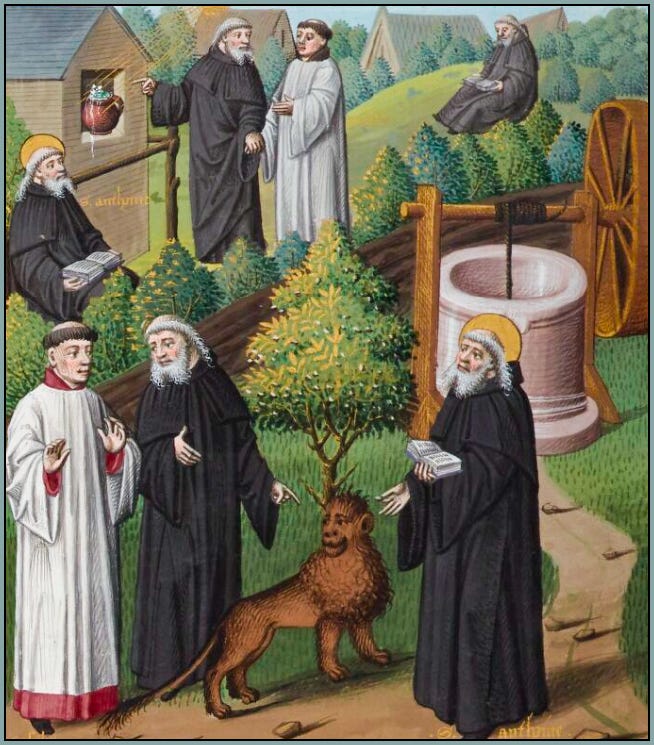

The saintly mystic Richard Rolle serves as a representative of medieval writers who fervently extolled consecrated virginity and portrayed sexual pleasure, or even romantic love, as little more than a lamentable danger to the health of the soul. In the previous article I quoted from Rolle’s book Incendium Amoris, contrasting his passionate love for God with his zealous disdain for the “fleshly love” of marriage. But here also we can discern a certain paradoxicality, and it speaks in praise of earthly marriage and human sexuality, even if it appears that Rolle’s words do not.

The paradox that I’m referring to recalls the relationship, explained in the previous article, between the exception and the rule: the exception “proves” the rule, because it helps us to put the rule to the test by shining a revelatory light on it. Rolle, a virgin who chose the path of heroic virtue, was an exception to the rule that prevailed in medieval society as in modern society: most people chose to marry and pursue a life of ordinary piety. To look at marriage through the lens of Rolle’s mysticism is to realize that his life is not a total negation or rejection of married life: in crucial ways, it is built upon married life, and we might even say it is a sublimation of married life. Christ is his mystical spouse, his “lovely Everlasting Love”; he is wounded by God’s “beauty”; his “heart” seeks God; his soul pursues God with “burning desire”; his “flesh thirsts” for God’s “embrace.” Rolle longs for God as a bridegroom longs for his bride, and Rolle is impelled toward mystical union with God as a bridegroom is impelled toward the spiritual and bodily union of Christian wedlock.

To turn base metals into precious ones is the deception called alchemy, and I see no reason to interpret Rolle’s spiritual romance as some sort of alchemical feat in which the “base” metal of marital love is transmuted into something vastly more chaste and holy. Consider the very language in which he proclaims his passionate yearning for God: the words he chooses, the imagery he conveys, the sensations he evokes are those of love between man and woman, and they testify to the goodness and beauty of marriage. By using the language of natural love and conjugal passion, writers like Rolle were, in a sense, consecrating these experiences and recognizing their indispensable role as icons of supernatural love and precursors of the virginal passion that leads saintly souls into the fiery depths of the divine Heart.

Thus, Rolle wasn’t turning lead into gold. He was turning silver into gold, and however vehement he may have been in exhorting his readers to seek out the gold and renounce the silver, his own words declare that the silver is still precious.

As the Psalmist says,

The wings of the dove are covered with silver,

and her feathers with precious gold.

The matter of "earthly pleasures" (and I think here only about those that are licit) is a crucial one. The fact that the saints unanimously seem to put into brackets (to say the least) even those pleasures that are licit, hides an extremely important teaching regarding TRUE (heavenly) pleasure(s). THIS ought to be carefully meditated - and without getting into troubles because of their skeptical attitude regarding marriage. But - and I strongly emphasize this - without a complete framework regarding the beginning of the mentioned "earthly pleasures" no right answer is possible. So, we must be very cautious!

I'm fascinated by the idea of the harsh words as a bitter medicine and a necessary imbalance to promote balance.

I love your closing image of the transmutation of silver to gold and the beautiful verses from the psalm about the dove's wings covered in silver and gold.