This is the third article in a series on medieval (and modern) marriage. The preceding articles are listed below.

In the words of Dame Joan Evans, a distinguished British historian of medieval life and art, “the early ages of Christianity were haunted by the sense that the life of the world and the life of the spirit were antagonistic.” We might say that the modern ages of Christianity are haunted by the sense that they are not antagonistic. Virtus, as usual, in medio stat: the truth, and with it a good and wholesome and happy life, lies somewhere between these two extremes.

Many saints have achieved their heroic status by living at the extreme—eremitical solitude; punishing fasts; severe poverty; long, laborious hours of prayer and meditation. Were their lives not good, and wholesome, and happy? Certainly they were, as far as I know. But history shows that saints such as these are, with regard to the entire human family, highly exceptional. And the exception, as the saying goes, proves the rule.

What exactly does this paradoxical proverb mean, though? How exactly does an exception prove a rule? Doesn’t it prove that there’s something not quite right, or even rather wrong, with the rule? It turns out that the meaning is disputed, and as H. W. Fowler, that titan of modern lexicography, rightly pointed out, the notion of an exception proving a rule is “constantly introduced in argument” and “much more often with obscuring than with illuminating effect.” He lists five possible senses of the phrase, dubbing two of them “the jocular nonsense” and “the serious nonsense,” and lamenting that “the serious nonsense” is “much the commonest use.” In any case, I suspect that the originary meaning lies in or near the old-fashioned usage of the English verb “prove”: to put something to the test, to assess its qualities, to establish its value. As the Psalmist says,

Prove me, O God, and know my heart,

assay thou me and know my thoughts:

see if a vile way be in me,

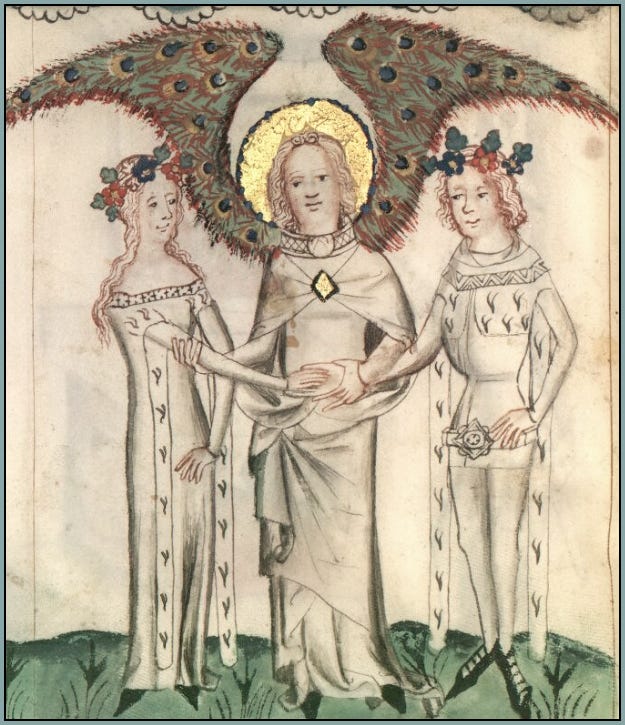

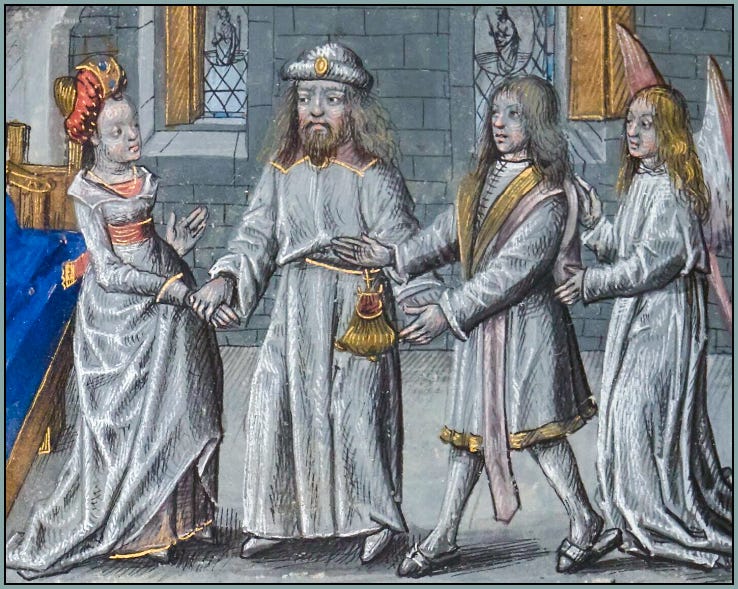

and in the way eternal, lead me.The exception proves the rule because it invites us to go back and put the rule to the test, and because it shines a new and revelatory light on the rule. For every era and region in which Christianity was practiced on a large scale, heroic saints—with their extremes of mortification, asceticism, and mysticality—were the exception, and the rule was ordinary duty-fulfilling goodness allied with the eminently natural pursuit of bodily and intellectual pleasure. Likewise, though monasticism flourished during the Middle Ages as never before or since, and though the era is justly called the Age of Faith, voluntary chastity was the exception in medieval society, and marriage was the rule.

It is a sign of the times that a Google search for “St. Augustine” first directs the user to websites for the city of St. Augustine, Florida. My understanding is that Google did not exist in the Middle Ages, but if it did, every result on the first five pages, at least, would have pointed to one man: Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis, otherwise known as Augustine of Hippo, the Doctor of Grace.

Augustine’s influence on the religious thought of the Middle Ages was immense. The man was revered as a saint, his writings were regarded as highly authoritative, and his life served as a vital link between the ancient and medieval worlds. The historian John Contreni said it well: “His discussions of grace, predestination, free will, and the soul came to define Christian teaching for the west.”

Augustine wrote a great many things with which I would undoubtedly agree, along with many more that are beyond my ability to fully comprehend. He also said one thing, in the treatise On Marriage and Concupiscence, that I don’t agree with at all:

It is, however, one thing for married persons to have intercourse only for the wish to beget children, which is not sinful: it is another thing for them to desire carnal pleasure in cohabitation, but with the spouse only, which involves venial sin.

The marital embrace is sinful, simply because the primary motive is pleasure, rather than procreation? Good grief, what a thing to say in a world where people so often fail to maintain even the most rudimentary conjugal fidelity, and where countless souls have wept and gnashed their teeth under the scourge of serious sexual sins like fornication and adultery. Why did the good God punish spouses with such intense and long-lasting desires for unitive pleasure if the only licit objective in exercising their conjugal rights is reproduction? The only way I can accept Augustine’s assertion here is if “venial sin” is intended to mean something more like “spiritual imperfection”: to know one’s lawful spouse partakes of supernatural goodness when the desire is procreative; when the desire is carnal, the act is simply natural, and good only insofar as it accords with the inherent goodness of Creation.

No sweeping statement can be made on how exactly Augustine’s teachings filtered into the marital theology of the numerous preachers, scholars, and mystics of the Middle Ages. Nonetheless, it seems likely that his views set an enduring precedent of negativity, and I mean that more in the etymological sense: negating—denying—the inherent merit, or at least the inherent moral legitimacy, of carnal relations that occur within marriage and are not vitiated by overwhelmingly sinful motives, attitudes, or practices.

Let’s move from Augustine, as a representative of the transitional era between Antiquity and the Middle Ages, to St. Gregory the Great, as a representative of the early Middle Ages. He treats of married life in Book III of the Pastoral Rule, and though his thoughts on matrimony—which he calls a “most honorable estate”—are by no means harsh and disparaging, his views on marital sexuality recall those of Augustine:

Husbands and wives are to be admonished to remember that they are joined together for the sake of producing offspring; … when giving themselves to immoderate intercourse, … they exceed the just dues of wedlock.

The next sentence, worded rather strongly, again conveys a disconcerting negativity toward the physical pleasure that naturally accompanies the reproductive act:

Whence it is needful that by frequent supplications they do away their having fouled, with the admixture of pleasure, the fair form of conjugal union.

Later, Gregory speaks of an allegorical mountain whose heights represent a life of true chastity, and for those who are married, to stand on this mountain is “to seek nothing in the flesh except the fruit of procreation.” Interestingly, however, he departs from Augustine when he declares that intercourse motivated by carnal pleasure is not sinful, assuring the faithful that though “married life is not marvelous for virtue,” it is “secure from punishment.”

Moving on to the High Middle Ages, we have St. Hildegard of Bingen, a twelfth-century abbess and mystic who also seems to echo Augustine:

Let the man do as human nature teaches him, and seek the right way with his wife in the strength of his heat and the vigor of his seed; and let him do this with human knowledge, out of desire for children.1

Hildegard vehemently condemns intercourse that occurs during pregnancy, when conception is not possible. For the sake of discretion I will not quote from the passage I’m referring to, but it is shocking and leaves me in a state of utter confusion and dismay. I say nothing against a prudent sexual fast, which is as beneficial for body and soul as fasting from food, but to repeatedly impose nine months of total abstinence on every married man and woman in Christendom seems to me egregiously unwise.

Finally, Richard Rolle will be our representative for the Late Middle Ages. You may recall that I concluded Part One of this series with Rolle’s declarations of passionate longing for God: “After Thee my heart desires; after Thee my flesh thirsts.... Hail therefore O lovely Everlasting Love....” He was, alas, considerably less sanguine on the topic of marriage:

Truly, fleshly love stirs temptation and blinds the soul that she may not have perfect cleanness…. Therefore he that covets to love Christ, let not the eye of his mind look to woman’s love…, [which] distracts the wits, perverts and overturns reason, changes wisdom of mind to folly, withdraws the heart from God and makes the soul bond to fiends…. Therefore flee women wisely and always keep thy thoughts far from them.

Just to be clear, that final piece of advice was just about as unpopular in the Middle Ages as it would be today.

The passages above are deliberately chosen for their negativity, so they’re not the whole story, but they exemplify what was certainly a widespread mentality—at least among the literate class, many of whom were clerics. The vast foundation of medieval society was the unlettered laboring class, and what exactly the farmers, butchers, bakers, and candlestick-makers thought about marital theology or sexual morality is hard to say; though they perpetuated Christian civilization for one thousand years by raising generation after generation of faithful Christian children, they did not write books.

This brings us back to the exception and the rule. Augustine, Gregory, Hildegard, Rolle—they embraced chastity, whereas the rule in medieval society, as in modern society, was marriage. I thank God for their lives of exceptional holiness, but I also thank God for the grace of sacramental matrimony, the pleasures of matrimonial love, and the sacred duty of bringing forth and educating a new generation of human beings, who are, as the Psalmist reminds us, the crowning glory of God’s material Creation.

Furthermore, we can, rather paradoxically, use the lives and writings of medieval saints to help us prove—reveal the qualities of, establish the value of—Christian marriage. This will be our task on Tuesday.

This passage is from the second vision of Scivias, translated by Mother Columba Hart and Jane Bishop.

It's hard to say they are wrong when scripture says that chastity is superior to marriage, and that marriage should only be practised when one is 'hot'. Of course, be also says not to deprive one another.

"Now concerning the matters about which you wrote: “It is good for a man not to have sexual relations with a woman.” But because of the temptation to sexual immorality, each man should have his own wife and each woman her own husband. The husband should give to his wife her conjugal rights, and likewise the wife to her husband. For the wife does not have authority over her own body, but the husband does. Likewise the husband does not have authority over his own body, but the wife does. Do not deprive one another, except perhaps by agreement for a limited time, that you may devote yourselves to prayer; but then come together again, so that Satan may not tempt you because of your lack of self-control.

Now as a concession, not a command, I say this. I wish that all were as I myself am. But each has his own gift from God, one of one kind and one of another."

1 Corinthians 7:1-7

Thank you Robert for a fascinating essay, as always.

I have several thoughts.

The first is that I accept virginity/ chastity for the sake of the kingdom of heaven is superior to marriage, in that one's love goes straight to Christ rather than alongside/ through another person. That, I think, is why St John the Evangelist is called 'the beloved'. The other Apostles were married men.

My second thought is that God created married love; thus He created the joy of physical union in marriage - a union that is also open to life. He intended couples to experience that intense unitive pleasure as an intrinsic part of the marital bond.

Thus I do not understand the idea of 'carnal' love being separate from, and negatively contrasted with, 'procreative' love. In holy matrimony there is no distinction.

All God asks is that the couple reflect His own creativity in their marital love. Their love must be 'open to life'.

This does not mean, however, that conjugal love can only be expressed during the time of the month when the wife might conceive and is banned at all other times: during pregnancy, during breastfeeding, during times when conception is unlikely. What of couples who learn that they cannot conceive at all? That God has given them a cross of infertility? Are they therefore to be banned from conjugal love for good?

God wills the goodness of married love. He wants couples to reflect that goodness in their physical expression of love. They are to be generous towards one another - and at the same time generous to Him in engendering new life.

Before the 20th century understanding of a woman's fertile cycle, couples made love and babies followed- or not. Now, guided by prayer, prudence, discernment as to their circumstances and so on, couples can space their children using natural, not non-contraceptive, methods.

Artificial contraceptive is a great evil, as Humane Vitae says, as it pushes God out of the marital embrace when He ought to be at the centre of it.

Having written all this, you will realise that I reject the teachings of these past saints. These teachings are flawed.

As you remarked Robert, in an earlier post, they make me reach for the smelling salts!

I repeat, God created men and women to marry - and in their sexual union to express their love of Him and their love for each other.

His first miracle was the marriage feast of Cana: the wine jars overflowing with the best wine. That is how He sees marriage.

I will stop here though there is lots more to say.