Sunday’s essay, which introduced the Middle Ages as the Age of Angels, began with a reflection on Mont-Saint-Michel, which was not only a singularly captivating monument to medieval spirituality but also an active monastery and a favored pilgrimage destination.

The origin of the abbey can be traced back to one of those miraculous and disturbing legends that seemed to circulate so freely in the Middle Ages:

The story goes that in 708 the archangel Michael told Aubert, the Bishop of Avranches, to build a church on Mont Tombe for him. St Aubert ignored him at first, but the archangel returned and reputedly burned a hole in Aubert’s skull with his finger. The Bishop realized that he could ignore the archangel no longer and Mont Tombe was dedicated to Michael on October 16, 708. St Aubert built the first church on the island and it has been known as Mont Saint-Michel ever since.1

I’m not sure how to assess the historicity of this account, but the moral of the story is clear enough: if an archangel asks you to do something, do it.

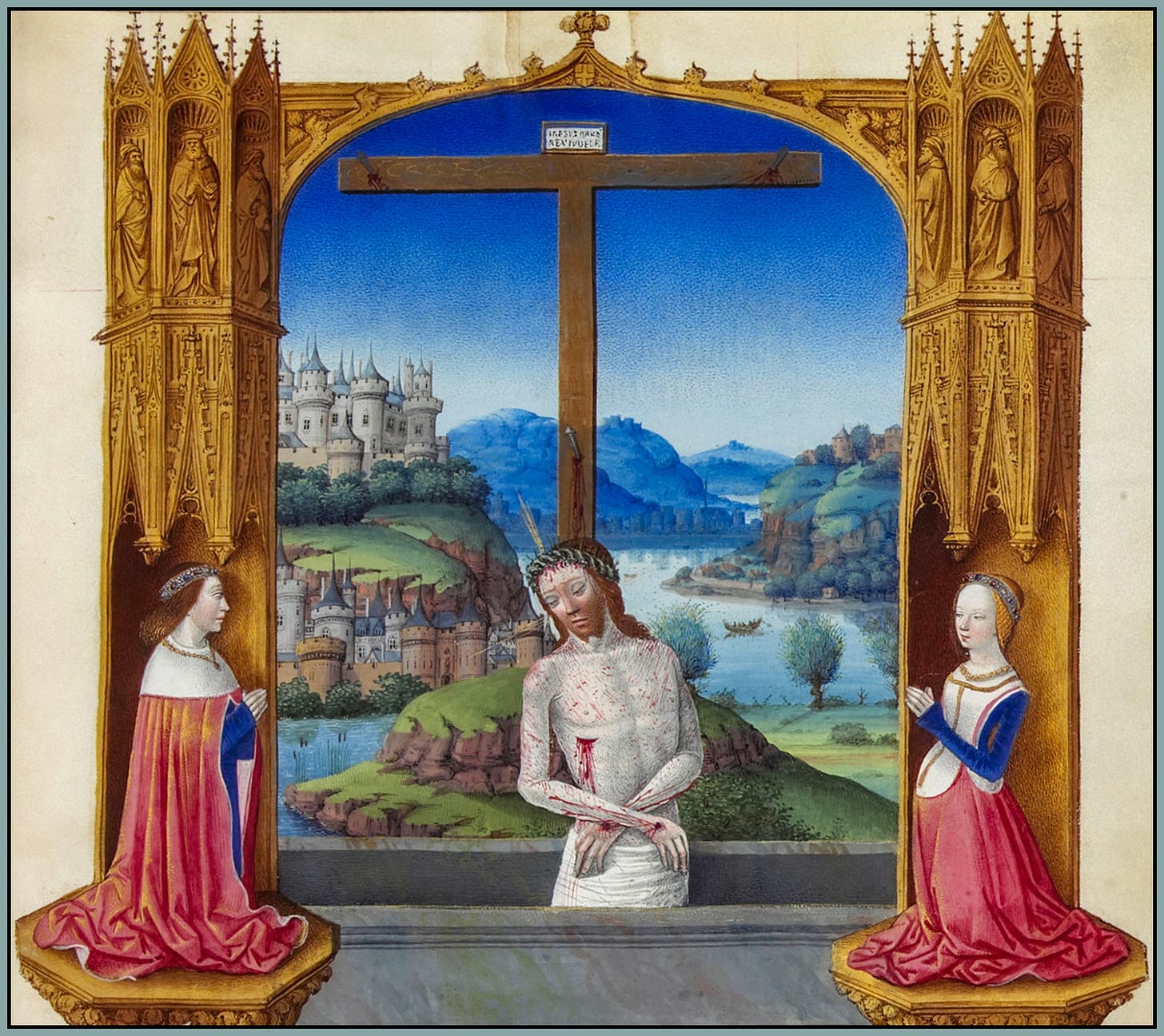

In any case, it is fitting that Mont-Saint-Michel should originate in a legend that evokes the literary qualities of a (rather grisly) fable, because it is one of the most literary places on earth—when I look at it, I feel like I’m seeing the real-life version of Camelot. But maybe it’s not so surprising that a poetically inclined medievalist like me, seeking refuge from the concrete jungles of postmodernity, would struggle to disentangle Mont-Saint-Michel from the dreamy realms of chivalric Romance. The more interesting thing is that medieval people themselves might have had a similar reaction. I can’t know what exactly they were thinking as they made their way to the Benedictine monastery on that tidal island “in peril of the sea,” as the pilgrims used to say. But I can ponder the medieval imagination through medieval artwork, and when I do so, I notice that depictions of idealized castles bear a certain resemblance to the Mount:

I guess what I’m saying is that maybe a few medieval people reached the same conclusion that I did: The Mount of St. Michael the Archangel is clearly a physical place, but it doesn’t really belong in the physical world. It belongs, first and foremost, in a faerie tale.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Via Mediaevalis to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.