Of Flat Characters, Round Characters, and Saints

Benedict of Nursia, Gregory the Dialogist, and E. M. Forster

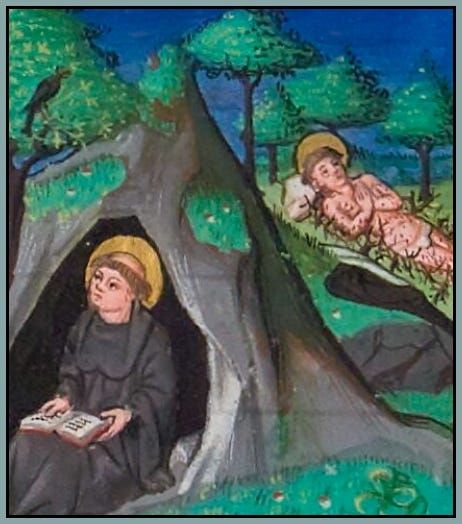

I said on Tuesday that I wanted to spend some time discussing the story of monasticism in medieval civilization. We began that story with St. Benedict of Nursia—and more specifically with a cave, somewhere in the hills outside of Rome, where both Benedict and western monasticism were reborn. We studied the saint’s life using the oldest and most reliable source we have: Gregory the Great’s Dialogues, written about fifty years after Benedict died. I suggested that a careful, reflective reading of the Dialogues reveals the father of western monasticism as “a man of Christlike disposition and extraordinarily heroic virtue.” Thus,

the commencement of western monasticism could hardly have been more auspicious; the magnificent Benedictine forest, flourishing in unimaginable abundance all over medieval Europe, could hardly have grown from a more pure or more vigorous seed.

The Dialogues is an enormously important historical-hagiographical work of the early-medieval Church, as indicated by the fact that its author is known in the East as Gregory the Dialogist. It was widely read and translated during the Middle Ages, and it has been extensively studied by modern scholars—perhaps too extensively, since by 1987 someone had written a book, over seven hundred pages in length, arguing that the Dialogues is a forgery: though it contains some excerpts from Gregory’s “authentic” writings, most of it was produced by an anonymous papal functionary seventy years after Gregory’s death. The author further explored this hypothesis in a second book, published sixteen years later and this time requiring a mere 464 pages.

In my view, this is one of those improbable yet non-falsifiable scholarly theories that raise questions not so much about a text like the Dialogues, which happens to be integral to the history of Western culture, but about whether university professors are spending their time in optimal ways. I make bold to suggest that the countless hours and immense effort devoted to those books might have been better spent helping students to read and analyze and learn from the Dialogues, whose authorship will be understood with perfect certainty only when time travel is invented—which is to say, never. Meanwhile, this “forgery,” a work of great literary and spiritual merit, and endorsed by many centuries of Christian tradition, remains a valuable and irreplaceable volume in the library of Western civilization—not least because it contains, in the words of a nineteenth-century historian, “the biography of the greatest Monk, written by the greatest Pope.”

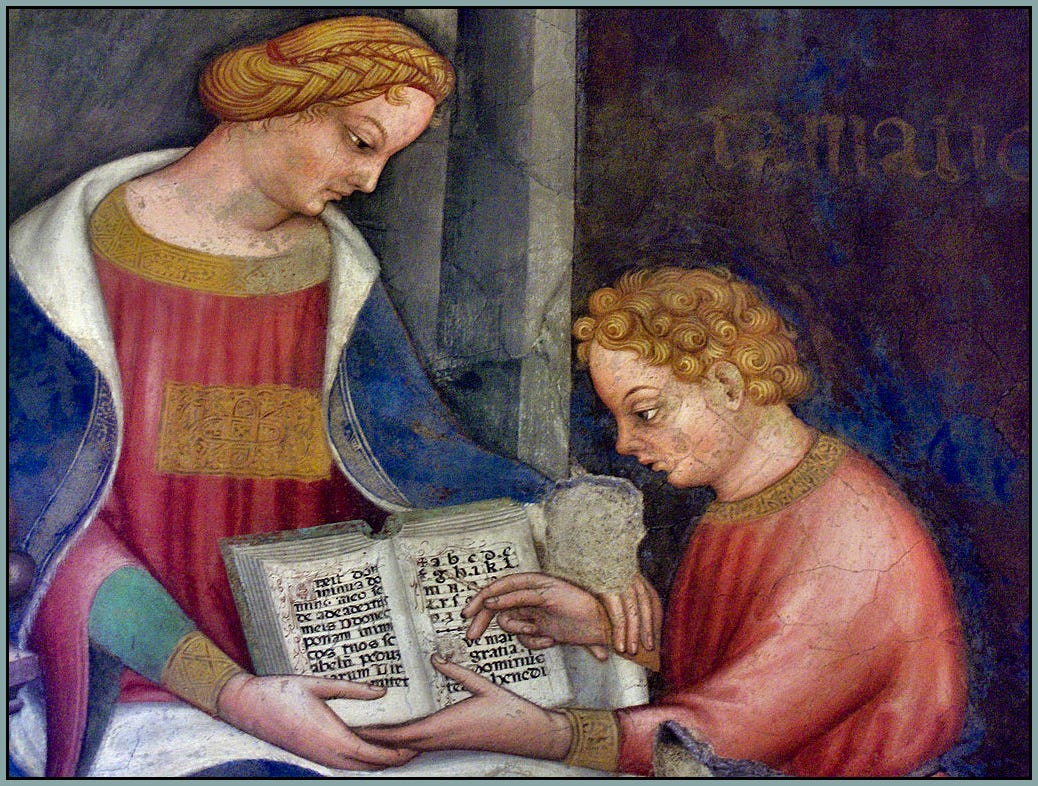

Gregory was a highly skilled rhetorician, which would make him (more or less) the sixth-century Roman equivalent of what we nowadays call a “good writer.” I put that term in scare quotes because it’s misleading, insofar as it suggests that proficiency in writing is primarily an attribute belonging to the individual, rather than a competency resulting from the individual’s education. Like any other scholar in medieval society, Gregory began his scholastic journey with the study of language; like many other saints in medieval society, his young intellect was molded by grammar and rhetoric. A thousand years later, when Christendom was in its death throes and almost everything once held sacred had to be judged in the court of the creed du jour, little had changed in Europe’s educational priorities: “Every person who had a grammar-school education in Europe” between the first century BC and the seventeenth century AD “knew by heart, familiarly, up to a hundred [rhetorical] figures, by their right names.”1 Names like anaphora, epistrophe, zeugma, isocolon, polyptoton, antimetabole, epanalepsis, antanaclasis. Scores of them. Every grammar school student.

This was not a form of institutionalized child abuse. It was how pre-modern Europe taught people to be good writers, and good thinkers, and good citizens of a Christian commonwealth.

In Tuesday’s post, I alluded to the fact that the characters in history books, however factual they may have been, often feel more like cardboard cutouts than men and women who breathed and wondered and yearned and suffered as we do. This is in contrast to the characters in novels, who sometimes seem so real that we gladly chat about them as though they live down the street and will one day do the things they would have done, if the book had not ended so prematurely.

The contrast I’m referring to is essentially that between “flat characters” and “round characters.” If you’re familiar with this terminology, you may be interested to know, if you don’t already, that it entered the literary lexicon fairly recently: the notion of flat versus round characters originates in lectures given in 1927 by E. M. Forster, a successful novelist associated with the artistic movement known as modernism (the name is much worse than the actual movement…). Forster’s treatment of the subject is insightful, and it doesn’t fall into the modern assumptions that we might expect from a modernist author—what I mean is that he doesn’t simply bemoan flat characters, typical of older literature, while praising round characters, which figure prominently in nineteenth- and twentieth-century novels.

Forster explains that flat characters

are sometimes called types, and sometimes caricatures. In their purest form, they are constructed round a single idea or quality…. The really flat character can be expressed in one sentence.

In fact, the flat characters of pre-modern literature could sometimes be expressed in one word: England’s morality plays had characters named Wisdom, Beauty, Ignorance, Lechery, Penance, etc. Forster mentions two advantages of flat characters, the second of which is quite thought-provoking and has especial relevance for hagiographical literature:

[Flat characters] are easily remembered by the reader afterwards. They remain in his mind as unalterable for the reason that they were not changed by circumstances; they moved through circumstances, which gives them in retrospect a comforting quality, and preserves them when the book that produced them may decay.

Round characters, on the other hand, exhibit the complex interiority that we perceive in the actions of real people, and in the thoughts of our own mind. “The test of the round character,” Forster says,

is whether it is capable of surprising in a convincing way. If it never surprises, it is flat. If it does not convince, it is a flat pretending to be round. It has the incalculability of life about it—life within the pages of a book.

I bring this up because the St. Benedict presented to us by Gregory the Dialogist is a fairly flat character. This should not, however, be interpreted as a fault in Gregory’s writing. It would be more accurate to describe it as a fault in our reading, insofar as we rely upon our modern authors, instead of our own imagination, to make characters round.

This issue brings us back to a topic that we explored here at Via Mediaevalis in an essay about the myth of “primitive” literature (and I really do mean “we”—that post ended up with fifty comments, and I’m grateful to everyone who joined the discussion). When someone’s literary diet consists primarily of modern novels and is deficient in ancient or medieval texts, the resulting imbalances can

make Sacred Scripture—and to a lesser extent, other ancient masterpieces such as the Odyssey and the Aeneid—appear rough, rudimentary, unrefined: in a word, primitive. Furthermore, they may shape our aesthetic sensibilities in such a way as to distance us, emotionally, intellectually, and artistically, from the Bible.

Being thus distanced from the Bible is of course a far graver matter than reading St. Benedict as a “flat character” in Gregory’s Dialogues. However, the latter problem is emblematic of an issue which is much larger, and which relates to that swollen river whose swirling currents erode the foundations of Christian culture, even as we strive and struggle to rebuild it: we should not be dependent on movies or other overstimulating media to make the saints and heroes of the past feel fully alive, and wondrously human.

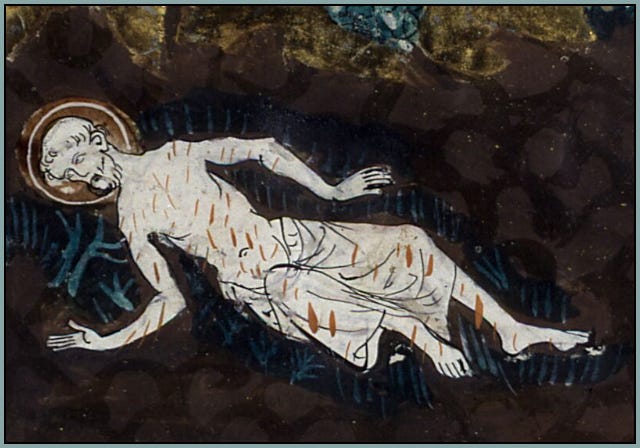

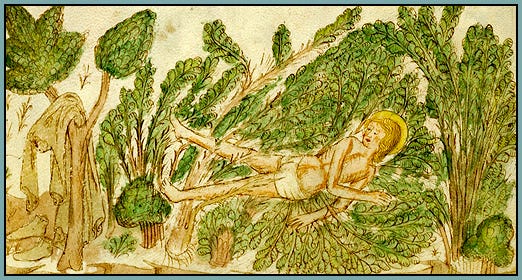

Let us conclude with an example. Gregory relates that St. Benedict was one day assailed by severe carnal temptations; the ordeal began when he was alone, but “the tempter was at hand.” Memories of “a certain woman” arose in his mind, and soon his “concupiscence” was so “inflamed” that he was “almost overcome with pleasure” and felt an urge to “forsake the wilderness.”

But suddenly assisted by God’s grace, he came to himself, and seeing many thick briars and nettle bushes growing nearby, he cast off his apparel and threw himself into the midst of them. There he wallowed so long that, when he rose up, all his flesh was pitifully torn: and so by the wounds of his body, he cured the wounds of his soul.

Gregory is describing a scene of tremendous intensity—psychological depth, extraordinary willpower, and appalling physical pain are interwoven with a story of spiritual conquest that is not only dramatic but also definitive, for after this event, Benedict was never again seriously tempted to abandon his monastic vocation.

All this intensity, however, is scarcely present in the text itself, which Gregory has endowed with the artistry of classical rhetoric but not with the narrative techniques of the modern novel, or even of Shakespearean drama. In a surface-level reading, Benedict has seductive thoughts that seem largely foreign to his own psyche, and he makes his horrifying decision almost as a matter of course, and then he appears hardly sentient as he casts his naked body into a torture chamber of thorns and nettles, so as to “wallow” there until the fire of carnal passion is extinguished. We are the ones who must make this Benedict less two-dimensional; it is through our imagination that the character gains what the real man, as a son of Adam, truly possessed: the allure of pleasure, the fear of pain, elusive ideals, importunate ambitions, conflicting desires, a deceptive memory, a faltering will, a failing body—in a word, humanity, the very same humanity which we all have received, and which I for one have enriched with far less virtue, far less wisdom, far less heroism than we find in the life of that singular young monk from Nursia.

Gregory, again drawing from his rhetorical treasury, continues his history with the words below. They now appear to us as a prophecy, for the saintly pontiff, writing in the sixth century, saw only a tiny fraction of the eventual Benedictine harvest:

“When this great temptation was thus overcome, the man of God, like soil well tilled and weeded, brought forth from the seed of virtue an abundance of fruit.”

Brian Vickers, “Shakespeare’s Use of Rhetoric,” in A New Companion to Shakespeare Studies, edited by K. Muir and S. Schoenbaum. Cambridge University Press (1971), p. 86.

Robert, have you had a chance yet to read Jeremy Holmes's "Cur Deus Verba: Why the Word of God Became Words"? If not, drop everything (so to speak), and please read it! His reflections on why man, as social animal, is naturally traditional, develops and requires a literary canon, and finds himself through assimilating this canon are, in my opinion, unique, and uniquely profound. I have read a lot in this area and have never found anyone who explores the theme better. It suits Via Mediaevalis hand-in-glove.

Interesting, as always.

I haven't read Forster's discussion, but from the quotes above he seems to focus on writing. The contrast between "flatness" and "roundness" seems to map fairly well onto some of the points Ong raised in "Orality and Literacy". I wonder, then, if you see "flatness" of character as emerging from older oral traditions, whereas "roundedness" would come later, with the emergence & spread of writing.

If "roundedness" and "flatness" were both available to Gregory, say, then we could suggest that Benedict's "flatness" was a rhetorical strategy, a choice - perhaps consciously intended to invite the kind of "work" from the reader that you describe above.

Put another way, if Gregory had had the option of making Benedict "round" - ought he to have?