Swine, Acorns, and the Art of Conversation

The Medieval Year: Tenth Day before the Kalends of December

The Medieval Year, a weekly feature of the Via Mediaevalis newsletter, gives us an opportunity to appreciate calendrical artwork from the Middle Ages, reflect on the basic tasks and rhythms of medieval life, and follow the medieval year as we make our way through the modern year. Please refer to the first post in this series for more background information!

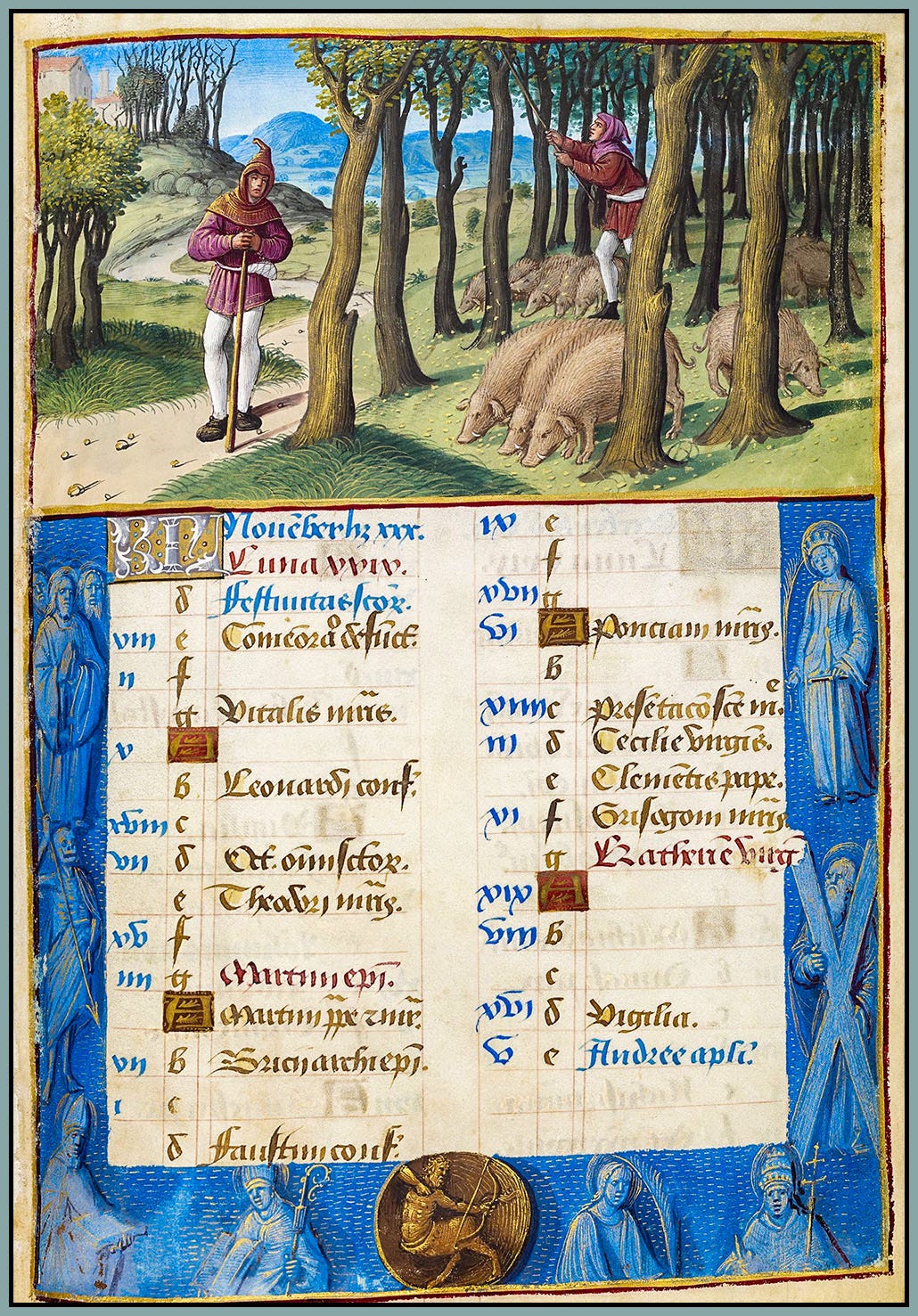

Let’s begin with another delightful calendar page from the Hours of Henry VIII.

The calendar section has some noteworthy details; let’s take a look at those before we discuss the labor of the month.

As I explained a few weeks ago, medieval civilization believed strongly in the relationship between heavenly bodies and human bodies. The signs of the zodiac were key markers of this relationship, and we see them frequently included in calendrical art. The medallion at the bottom of the page depicts Sagittarius as a centaur shooting an arrow. The period governed by Sagittarius begins today, November 22nd.

Some major feasts included in the calendar are All Saints and All Souls, St. Martin (in red ink), St. Catherine (also in red ink), and St. Andrew the Apostle (in blue ink). The blue-tinted border area has a lovely drawing of St. Catherine (top right), an ominous drawing of St. Andrew (middle right, holding the X-shaped cross on which he was crucified), and a rather alarming drawing of a skeleton holding a spear (middle left, for All Souls’ Day).

Finally, did you notice this little detail on the calendar line for St. Catherine?

Something seems to have gone amiss here, and what I find interesting is the way the artist just kind of accepted it and moved on. Though at first glance this page may not seem comparable in artistic terms to the larger paintings being produced around the same time (i.e., the early sixteenth century), it nonetheless is quite visually impressive and would have required prodigious skill—the quality of detail, given that the leaf is only about 10 inches tall and 7 inches wide, is extremely high. And yet … mistakes happen: diligence is one thing, perfectionism something else. In yet another medieval paradox, scribes and illuminators of the Middle Ages were curiously detached from certain kinds of “defects”—one minute they’re meticulously drawing a marginal decoration of extraordinary intricacy, and the next they’re drawing a “rectangular” frame whose lines are not very straight.

While we’re on this topic, I want to share with you my all-time favorite “typo”:

Ponder this for a little while before you keep reading—see if you can figure out what’s going on here.

The scribe accidentally omitted a sentence, and he “solved” the problem by including the sentence at the bottom of the page, connecting it to a rope, and giving the rope to a helper who is attempting to drag the sentence into its proper place.

The labors of November are concerned primarily with maintaining a good meat supply for the winter. Hence the hogs, which are happily feasting (from their perspective) and fattening (from the villagers’ perspective) on the many acorns provided by a pleasant oak grove. The two swineherds are dressed quite warmly; a late-autumn chill is in the air. One is busy serving up a second course by knocking reluctant acorns from the branches, and the other seems to be taking the medieval equivalent of a coffee break. Or maybe he’s pretending to keep an eye on the herd while the other does the knocking. In any case, that swain on the left looks like trouble. A disaffected worker, no doubt, who actually wants the swine to get lost. He doesn’t care. He’s reached his limit. Three times this week, four times last week—he is done. Done chasing pigs through the woods, done chasing them down the footpath, done making a fool of himself in front of Alice,1 who somehow always needs to fetch water from the spring when the wretched beasts decide to make a run for it.

Can you imagine being out in the woods for hours on end with no phone, no camera, no smartwatch (in fact no clock of any kind), no book, no crossword puzzle, no occasional airplane flying overhead—in other words, with nothing standing between you and prodigious boredom except a dozen pigs and one human companion? William and Richard2 must have mastered the art of conversation—an art that, it seems to me, is in serious decline these days. What exactly they talked about we’ll never know. The village could not possibly have supplied enough births and deaths and stories and scandals to fill all those hours. But then again, it didn’t need to. The point of conversation is not to talk about something. The point is to talk—the pleasure of speaking and interacting with a living, feeling, thinking being who is so like oneself and yet so very different also. Nowadays, if people have “nothing” to talk about, the conversation, if it ever began, is over. Out comes the phone. Guy de Maupassant, the famous French short-story writer, knew better:

Conversation … is the art of never appearing a bore, of knowing how to say everything interestingly, to entertain with no matter what, to be charming with nothing at all.

Alice (appearing in the documentary evidence as Alicia) was perhaps the most common female name in early-thirteenth-century England. Other popular choices were Agnes, Editha (presumably Edith in spoken form), and Emma.

These were probably the two most common male names (written as Willelmus and Ricardus) in early-thirteenth-century England. John (Iohannes), Robert (Robertus), and Hugo were also popular.

If small town life before the internet and iphones in the 70s and 80s, still contained clues as to what these guys did in the medieval era to kill the time, I'd venture to guess there would have been hours and hours of bawdy humour, jokes and riddles, physical assaults on each other (and if they weren't throwing acorns at each others heads, I'd be shocked), and of course gossip, complaints about the priest, cure and Seigneur, and an awful lot about Alice and Emma. If you were lucky, you'd get a companion who could tell a tall tale and sing a good tune and didn't try to push you into the river

The British Library posted some men-beating-trees-to-feed-the-pigs illuminations on instagram a few days ago and it really struck me – these images seem so unremarkable in passing, but when you look at them while sitting by a window that looks out over a grizzled oak tree raining acorns over a bed of leaves...suddenly you're *there*. I imagine William and Richard were also much keener observers of nature than the average person today, which would have provided additional ongoing fodder for conversation! I notice this keenness in my toddler, who points out bugs on the ground and birds in the air that would have gone unnoticed in my periphery...he's mastered the art of medieval living far more than I!