The Angels in Medieval Eyes

“I saw,” says Dante, “festive angels, wings opened wide, more than a thousand, each distinct in radiance and in kind.”

The Via Mediaevalis series on medieval angelology continues. I hope that you can find time to read some of the previous essays on this topic, if you haven’t already:

Woven into the previous article were two questions: Why did medieval Christians give special consideration to the creation of the angels, which is not mentioned in Genesis and was therefore shrouded in uncertainty? And why does co-creation—that is, the notion that angels participated in the creation of the material world—seem to appeal, with such deep and resonant meanings, to the human imagination?

I offered a partial answer to both questions at the end of the article. One of the keys to medieval culture’s rich and beautiful and highly intellectual devotion to angels was a doctrine that still exists but has largely faded from the landscape of daily life: there is unique kinship between angelic nature and human nature, and therefore a unique friendship between angels and men. The angels are close to us, ontologically speaking; they understand us and take an interest in our lives, as the rocks and trees and beasts never will; they delight in helping us, just as we delight in helping those who are weaker and more vulnerable than ourselves. They have reason, advanced cognition, and an eternal destiny, as we do. They are endowed with free will, as we are, though they have already reached the state in which freedom is immune to temptation. And though they are not naturally united to bodies, they can assume bodies and appear to us as corporeal beings.

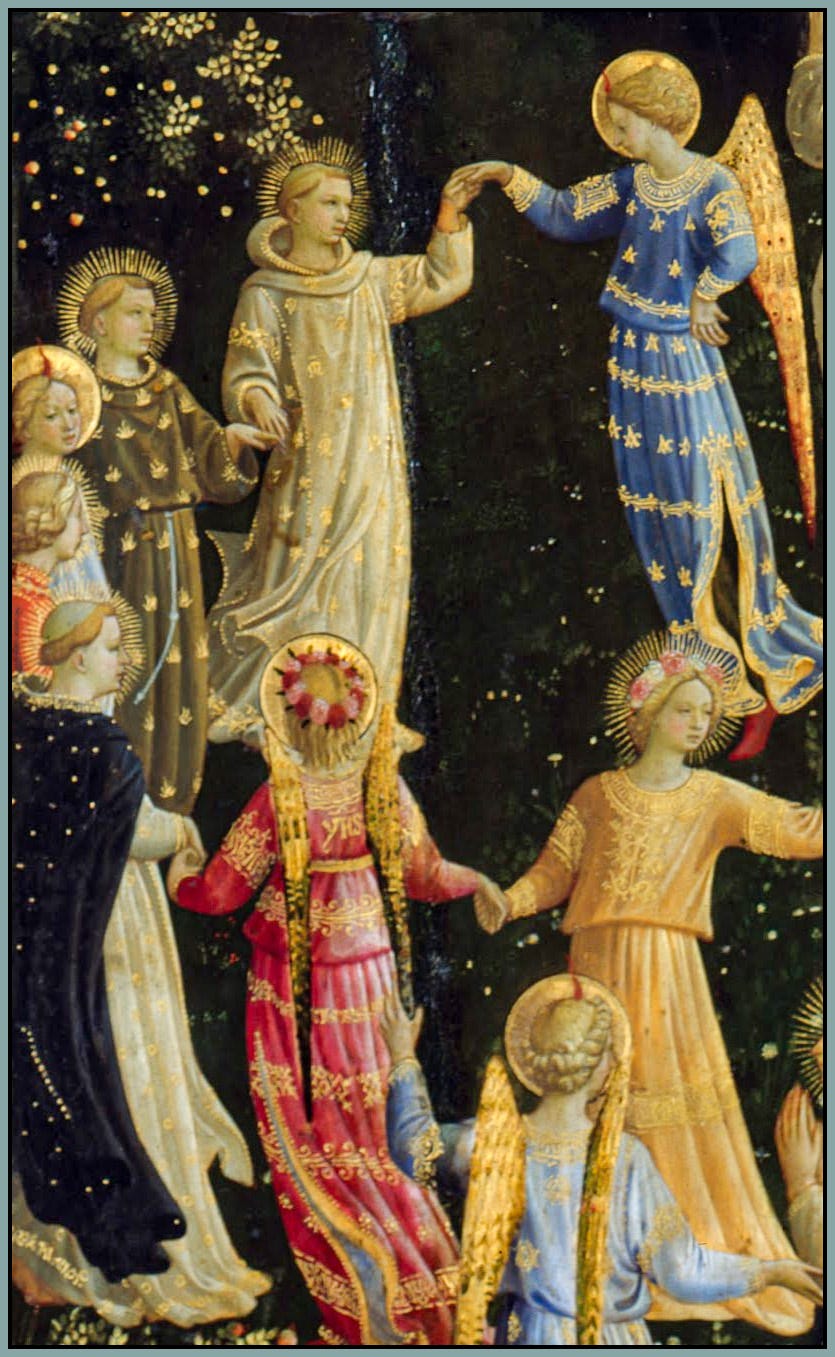

The angels read our poetry, they listen to our sermons, they look at our paintings—and I say this with all gravity, and no sentimentality. Dante’s Paradiso must be a feast nonpareil for their godly, crystalline minds, and I suspect that they find particular satisfaction in contemplating our attempts—so long as these attempts are spiritually and aesthetically sound—to create visual representations of themselves. What is more enchanting than the thought of an angel gazing with pleasure upon Fra Angelico’s picture of angels dancing with men?

I see no reason why beholding the Face of God would make the angels insensitive to lesser manifestations of goodness, truth, and beauty. On the contrary, if our artwork reflects in some small way the eloquence and skill of the divine Artist, they will savor this pale reflection more truly and more joyfully than we ever could; let us not forget that Dante spoke of angelici ludi—the playful celebrations of the angels. And since they exist outside of time, their schedules are never full; their duties in the heavenly choir, for example, do not prevent them from joining us in church. If they have time to protect us, as the guardian angels clearly do, surely they have time to pray and sing with us as well (though I fear that they want nothing to do with many of our so-called hymns these days).

Again, I say this with all gravity. I hope it does not come across as fantastical or melodramatic. Medieval culture teaches us that the angels are pure and glorious and wondrously holy, and that they are a very real part of our world, of our society, of our daily life. We cannot see them; nor can we see the air, and yet we breathe it. We cannot hear them; nor can we distinguish one violin in an orchestra, and yet it plays. We cannot touch them; nor can we touch love, and yet people feel it, and sometimes die for it.

Such thoughts need not wander in the forest of mere theory. They are practical; they are life-altering. No one can adequately explain some of the awe-inspiring accomplishments of the Middle Ages—the Gothic cathedrals, the vast array of monasteries, the astonishing doctrinal cohesion. Could part of the mystery reside in a uniquely powerful awareness of, admiration for, angelic presence? In a uniquely serious commitment to living in union with the angels? And could we not, to some extent, do the same? Surely some of you now reading this are teachers, as I am. There are days when half the class seems to be absent and those who showed up seem to be collectively half-alive: questions linger, unanswered; witticisms decay, unappreciated; enthusiasm dies, unrequited. How does one stay motivated on such days? Lecturing is an arduous task, on multiple levels—why go on, when nobody cares?

The angels care. If I am speaking truth, they are present, they are receptive, they are interested; if I am speaking well, with respect for the rhetorical principles that God Himself designed into the miracle of language, they are pleased. They can take my words to the students, at a more opportune moment perhaps. However, they cannot read my mind. They will do their work, but I must first do mine: I must lecture, and lecture well. It’s worth it—the angels are listening.

Whatever you’re doing, if it’s good, beautiful, true—if it’s God’s will—it’s worth it. Does the world care? Will the world thank you for it? Praise you for it? Pay you for it? Who knows. But the angels see it, hear it, enjoy it, love it: and they are, as Dante says, “so numerous / that never did man’s thought or speech / attain a sum so vast.”

The passage below was written by David Keck, the historian I’ve mentioned a few times in this series. He says so much, in two arresting sentences, about medieval culture, modern culture, and the chasm that separates the two:

In the modern world, the impulse to learn about human nature from closely related beings has shifted subjects from seraphim to simians. Whereas modern scientists study the origins of the apes to uncover clues about humanity, medieval theologians investigated angels.

What a stunning, baffling, nauseating statement. A tale of two societies: the first seeks to know itself, and studies the angels; the second seeks to know itself, and studies the primates. “O, woe is me,” as Shakespeare’s Ophelia said, “To have seen what I have seen, see what I see!”

In the grand order of the Cosmos, the angels are like our extended family. More than anything else that the good God has created, the angels are a spiritual mirror to us—look at them, study them, contemplate them, and you will know more about yourself.

Consider the way that angels are portrayed in medieval artwork. We studied this illustration about a month ago:

Subtract the wings, and the angels are elegant, noble, self-assured humans. We also saw this next image in a previous article:

The angels are simply human beings with halos, and rightly so, for in the biblical account that inspired this painting (Genesis 18:2), as in other such encounters (Genesis 32:24, Joshua 5:13), the angels appear as ordinary men. Here are a few more examples:

My intention here is not to deprecate other legitimate artistic styles; nevertheless, I must draw attention to the contrast between these medieval angels and the chubby cherubs of the Baroque era, or the digitally enhanced angelic superstars of the Google era. Christian artwork should not create too great a distance between men and angels; it should not build psychological walls that make us more alone than we actually are. We ought not feel so different from the angels as to make us fear, or simply forget, to seek their companionship. And as the next image reminds us, we ought not depict them in such a way as to suggest that they are indifferent to ours.

I have been eagerly awaiting the opportunity to share this next piece of artwork with you. What you see below is the top-left panel from a pair of doors adorned by relief sculptures. Made for Hildesheim Cathedral in Germany, they date to the early eleventh century and are known as the Bernward Doors, after the bishop who commissioned them, St. Bernward.

We are in Eden. God, having already created Adam, now awakens him after creating Eve. The human race, man and woman, is born. And someone has come to see us.

My friends, this is one of those moments when I find myself simply lost in the mystical depths of the medieval mind. Someone chose, surely with much reflection, this particular depiction, this particular gesture—and what a profoundly expressive gesture it is. What did it mean to the medieval artisan when he so painstakingly sculpted it? Wonder? Admiration? Brotherly affection? The meaning, for me, is clear enough. The angel sees that God has fashioned, from the dust of the earth, beings—companions—who are, in a very special way, like himself. And he is overjoyed.

The angel’s gesture is precious and powerful to meditate upon, and yet what amazes me even more is the posture of God as He awakens Adam. The kind of image I pray will stick with me…that an angel will help me call up when I need it most.

Thank you for this series of essays. They are helping me restructure my view of reality. I was wondering if you could clarify what you mean when you say, "However, they cannot read my mind." How do you propose interacting with the Angelic? Does it have to be verbalized out loud?