The Exsultet, The Happy Fault, and the Queen of Heaven

“Had not the apple taken been, the apple taken been, / nor had never our lady been the queen of heaven.”

This essay was originally published on New Liturgical Movement.

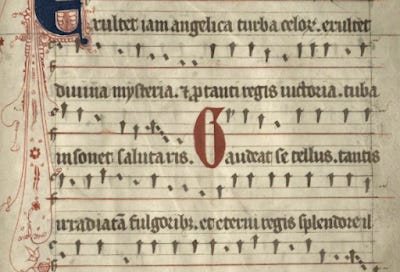

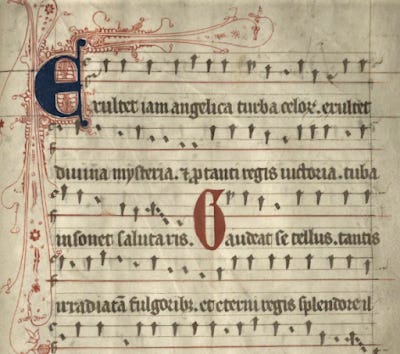

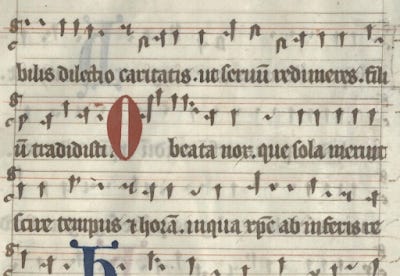

Roman rite Catholics recently had their once-per-year opportunity to savor the praeconium paschale, an ancient liturgical hymn known in English as the Easter Proclamation and commonly referred to by its supremely fitting first word: exsultet,1 “let (the angelic host of the heavens) rejoice.” Chanted by the deacon during the liturgy of Holy Saturday, the Exsultet is a poetic masterpiece that fills the opening moments of the Easter vigil with mystical pathos and brings key paschal motifs—luminosity, deliverance, communal joy—into glorious relief.

O Necessarium Peccatum...

Originally one among various prayers with which western European rites celebrated the lighting of the paschal candle, the Exsultet dates to the fourth or fifth century and came to Rome with the Gelasian sacramentaries. It appears to have been influenced by the thought of St. Ambrose, and it may have been composed by him. As we see in other early Christian writings (and in Holy Scripture), the Exsultet draws much poetic and spiritual energy from the eloquent pairing of opposites that rhetoricians call antithesis. The antithesis of light and darkness is especially prominent and informs the entire hymn; the following examples are from the opening and concluding sections of the text:

Let the earth also rejoice, illumined by such brightness: and, enlightened with the splendor of the eternal King, may it know that the darkness of all the world has been dispersed.

We pray Thee, therefore, O Lord: that this candle, consecrated unto the honor of Thy Name, to destroy the darkness of this night, may unfailingly endure.

The Easter Proclamation treats of another antithetical relation—namely, the mysterious kinship of Adam’s ruin and Christ’s Redemption—that culminates in our most well-known formulation of a famous theological paradox: O felix culpa..., “O happy fault, that deserved to have such and so great a Redeemer!” Holy Church is bold indeed to speak thus of Original Sin, which the Exsultet describes also as the “truly necessary sin of Adam.”2 But lovers tend to be bold in their use of language, and so do poets, and since the Church is both a lover and a poet, we should not be too surprised. Theologians, however, must be more circumspect, and indeed, the metaphysical implications of a “happy,” “fortunate,” or “fruitful” sin—all of these meanings are possible with Latin felix—have long been controversial:

Augustine was ambivalent about the idea, while other church fathers opposed it or maintained a discreet silence. In fact, the felix culpa verse was contested and at times even stricken from the liturgy. It does not appear in the influential Romano-German Pontifical (tenth century), and Abbot Hugh of Cluny (d. 1109) purged the offending sentences from the Cluniac Easter rite.3

Thankfully, the felix culpa survived and is still with us, returning every Easter to supply the overly analytical modern mind with some much-needed paradoxicality. And though it is sufficiently sublime to regard a disastrous transgression as “necessary” because it occasioned the Incarnation and salvific death of our dear Lord, the piety of the Middle Ages saw fit to exalt also Our Lady as the cherished fruit of Adam’s fateful yet fertile sin.

Adam, the Apple, and “Heuene Qwen”

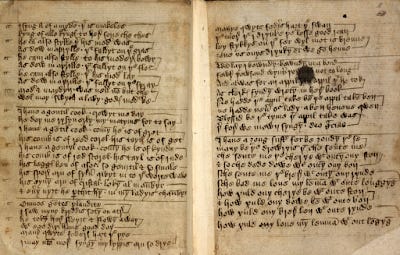

The early-fifteenth-century Middle English poem “Adam lay ibowndyn” is found, along with verse of a much less edifying nature, in an artifact known as Sloane Manuscript 2593.

Dr. Kathleen Palti transcribed the text as follows:

Adam lay ibowndyn bowndyn in a bond

fowr’ þowsand wynter þowt he not to long

And al was for an appil An appil þat he tok

as clerkis fyndyn wretyn in her’ book

Ne hadde þe appil take ben þe appil taken ben

ne hadde neuer our lady a ben heuene qwen

Blyssid be þe tyme þat appil take was

þerfor’ we mown syngyn deo gracia

Below is a rendering in quasi-modern English.

Adam lay bound, bound in a bond,

four thousand winters thought he not too long;

and all was for an apple, an apple that he took,

as clerics find written in their book.

Had not the apple taken been, the apple taken been,

nor had never our lady been the queen of heaven.

Blessed be the time that apple taken was,

therefore we can sing, “Deo gratias.”

When I first came across this otherwise unremarkable specimen of late medieval religious poetry, I had never seen a literary or liturgical text that explicitly connects the celestial reign of the holy Virgin to the felix culpa. It turns out that this theme is not unique to “Adam lay ibowndyn,” but it is perhaps uniquely memorable and touching when encountered in such a homely and heartfelt expression of western European folk piety. And though the text is clearly the work of an unpretentious poet, the rhetorical craftsmanship may be more refined than it initially appears: the author specifically celebrates the coronation of Mary; this event carried a sense of finality and completion because in the mystical chronology of Catholic devotional practice, it was subsequent to the Resurrection, the Ascension, and the descent of the Holy Ghost.4 The queenship of Our Lady thus functions as a synecdoche for all the glorious moments that followed the seminal triumph of Good Friday, and perhaps even for the glorious totality of salvation history.

The folk theology of “Adam lay ibowndyn” is a lovely complement to the profound liturgical theology of the Church’s praeconium paschale. The readings and ceremonies of the Easter vigil, which are utterly preoccupied with Christ’s momentous and long-awaited victory over sin and death, do not lead us directly into reflections on Our Lady’s role in the paschal mysteries. Thus, I am grateful for the work of an anonymous English poet who reminds me that Adam’s necessarium peccatum brought Mary of Nazareth into my life—O happy fault, that gave us so great a Queen and Mother!

The Marian inflection of the felix culpa also reminds us to honor Our Lady’s subtle presence in the Exsultet. The hymn’s affection for bees5 is somewhat curious until we recognize that these favored creatures, whose virginal labors produced the paschal candle, beautifully symbolize the virgin Mother of Him who, as a pillar of fire, led the Hebrews out of bondage: “And now we know the praises of this pillar, which the glowing fire enkindles unto the glory of God.... It is nourished by the melting wax, which the mother bee brought forth for the substance of this precious lamp.”

The Modern Life of a Medieval Poem

Certain works of art have a mysterious ability to survive the ravages of time. The author of “Adam lay ibowndyn” could never have dreamed that this short, simple, vernacular poem would—some five hundred years in the future—inspire several choral compositions and even reach the status of a paraliturgical text. But this is precisely what has occurred, and I myself heard the poem sung by a professional choir as part of a solemn musical oratory of Advent. It was a delightful experience, and I would be even more delighted to hear a fine polyphonic setting of “Adam lay ibowndyn” during this sacred and joyous tide of Easter.

As with other Latin words in which an initial s is preceded by the prefix ex- (e.g., exspiro, exstasis, exsurgo), exsultet can also be spelled exultet (expiro, extasis, exurgo). The available evidence suggests that the exs- spelling was preferred in the classical period.

The complete locution is “O certe necessarium Adae peccatum, quod Christi morte deletum est! – O surely necessary sin of Adam, which has been blotted out by the death of Christ!” The notion of a necessary sin is, from a strict theological perspective, highly problematic. Some scholars have argued that, despite the apparent similarity, “necessary” may not be the intended meaning of necessarium. The only proposed alternative that I find plausible is “unavoidable.”

Barbara Newman, Medieval Crossover: Reading the Secular against the Sacred (University of Notre Dame Press, 2013), 14.

In the York cycle of mystery plays, for example, the coronation of Mary was dramatized in the second-to-last play; the last was “The Judgment Day.”

This affection is more conspicuous and emphatic in pre-sixteenth-century texts of the Exsultet, which included an additional section that praised bees as “truly blessed and wonderful” and explicitly mentioned their symbolic connection to the Virgin Mary.