Last week we talked about medieval romance literature—King Arthur, Sir Orfeo, etc.—as a quest not for love or pleasure or martial glory, but for restoration, reunification, wholeness. However, literary conventions are not “laws,” just as the meter in a poem is not a metronome rhythm. Poets depart from their chosen metrical form in ways that create meaning, and medieval authors could do something similar with the structure and content of their narratives.

The romance of Tristan (also spelled Tristran) and Ysolt (also spelled Iseult or Isolde) was very popular in the Middle Ages and retained its appeal well into the modern era—a story must be good if its success stretched from the middle of the twelfth century to the middle of the nineteenth, when Wagner composed his opera Tristan und Isolde. (Apparently a cinematic adaptation appeared in 2006, but I know nothing about it and assume that it massacres the literary works that preceded it.) The Tristan tale, which varies from one version to another, is overtly scandalous; this surely has contributed to its popularity, whether in the twelfth century or the twentieth.

How exactly Tristan and Ysolt are understood and enjoyed in modernity is of little interest to me, since modern culture is perfectly willing to produce scandal for its own sake, or for the sake of vulgar entertainment, or psychological manipulation, or YouTube likes. The culture of the High Middle Ages, in contrast, had no illusions about the ruin, whether temporal or eternal, that would naturally result from gravely immoral conduct. And for a civilization built upon the Gospel, the words of Christ were not easily forgotten: “Whosoever shall scandalize one of these little ones that believe in me, it were better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck, and he were cast into the sea.” Scandal and immorality were far from absent, but that’s because medieval Christians, like Christians of any other age, were weak—not because they imagined that moral deviations were harmless amusement, or that virtue was impossible for ordinary mortals, or that public scandal would somehow make them more “free” and “independent” and “self-actualized.”

What are we to make, then, of Tristan and Ysolt in the culture of medieval Christendom? How can we explain the prominence of two superficially admirable characters—Tristan has even been described as “the ideal lover” in the French troubadour tradition—whose adulterous, treacherous love affair is an outrageous insult to Judeo-Christian morality? The answer becomes more clear if we understand the essential structure of medieval romance, and then consider what it means when a romance narrative departs from this structure.

One version of Tristan and Ysolt, entitled Chievrefoil, appears in the collection of lays composed in the twelfth century by Marie de France. Modern readers might look closely at her text, trying to discover what she really thought about the adulterous affair. I admit that we can never be entirely certain about the depths of another’s mind: if someone is determined to believe that Marie approved of their “true” “love,” in contrast (I suppose) to the not-quite-so-amorous love that animated countless sacramental unions and gave medieval society a cohesive stability that is unimaginable in the twenty-first century, there’s no definitive counter-argument I can make.

But when we form such conclusions about medieval authors, we must be careful to ensure that we’re actually looking into the past, and not into a mirror. Though the materialistic air of modernity is mostly nitrogen and oxygen, every breath in the medieval West was well mixed with the Christian spirit. A brilliant woman like Marie de France, probably the greatest female poet of the Middle Ages, would be bold indeed to look with favor on Tristan and Ysolt, especially considering that she begins her large collection of romance poems with these words:

Ki Deus ad duné escïence

E de parler bone eloquence

Ne s’en deit taisir ne celer,

Ainz se deit voluntiers mustrer.1(Those to whom God has given knowledge

and eloquent speech

should not be silent or hide away

but should willingly demonstrate it.)

These are literally the very first words of the prologue. For Marie, her knowledge and poetic eloquence come from God, and she writes in fulfillment of her obligations to Him and to her earthly society, which is always in need of art that is good, and beautiful, and true. And speaking of truth, these are the first words of Chievrefoil:

Asez me plest e bien le voil,

Del lai qu’hum nume Chievrefoil,

Que la verité vus en cunt

Pur quei fu fez, coment e dunt.(Greatly it pleases me

to tell you the truth

of the lay that men call Chievrefoil:

why it was made, how and from whom.)

Isn’t this a curious way to begin a fictional poem? She’s going to tell us “the truth” of the romance of Tristan and Ysolt? She is indeed, because she knows that there is truth beyond what we see and hear, and that poetry can convey this truth in a way that material realities and factual events cannot.

Marie’s adaptation of Tristan and Ysolt is brief and tells very little of the story. A much longer version, which survives only in fragments and integrates Tristan into the legendary world of Arthurian romance, was composed by Thomas of Britain, also in the twelfth century. A more complete picture of the narrative emerges from three versions written by Béroul (c. 1170), Eilhart von Oberg (c. 1175), and Gottfried von Strassburg (c. 1210). Here’s a synopsis:

Ysolt, a young woman living in Ireland, is betrothed to King Mark, of Cornwall, a cowardly monarch whom she has never seen. Tristan, the king’s nephew, is entrusted with the task of bringing her back to England. Ysolt’s mother is worried that Ysolt won’t be too excited about marrying King Mark, so she prepares a love potion and sends it along with them. The two young folks drink the potion by mistake, fall madly in love, satisfy their mutual lust, and end up in an adulterous affair that leads to dangers, intrigues, and opportunities for the two protagonists to make cunning escapes. So far the plot would fit pretty easily into the crowd-pleaser molds used in Hollywood, but the ending would require some adjustments: Ysolt returns to King Mark. Tristan goes into exile and marries someone else, but—and this is a very interesting detail—does not consummate the marriage. Tristan ends up mortally wounded and sends for Ysolt, but after hearing harsh words from his understandably jealous wife, he dies in despair. Ysolt arrives after his death, and then she dies too.

An early-twentieth-century Romanticist painting shows the two “lovers” dead on the ground. Ysolt’s dress has predictably slipped down so that one of her breasts is showing, and their corpses are elegantly arranged, one on top of the other, with serene half-smiles on their faces. What nonsense. They died in despair, enslaved to carnal pleasures that are as fleeting as a fresh breeze in midsummer, and medieval readers—at least those who hadn’t charted a course toward the same fate—knew what awaited them on the other side.

If Tristan and Ysolt romances give the impression of serious moral ambiguity, this shouldn’t surprise us too much. Great works of medieval literature were not given to heavy-handed moralizing, in part because everything in medieval society already existed within a clearly defined and almost universally accepted moral framework. The modern mind falters, maybe completely breaks down, when attempting to imagine a Europe in which you could travel from southern Italy to the British Isles and anywhere in between, and virtually every person you met would have the same basic ideas about what is right and what is wrong. (Putting those ideas into practice, of course, is another question.)

However, the key point I want to make in this essay is that the story is not as morally ambiguous as it appears. If we place Tristan and Ysolt within the tradition of medieval romance literature, and ponder it accordingly, we see that the story is actually a powerful condemnation of, and warning against, their actions. The essence of romance is the journey from integration, through disintegration, to reintegration. The fundamental satisfaction that these stories offer is their vision of adventures, mysteries, hardships, and trials that ultimately achieve the restoration, as in the Christian religion itself, of personal and social wholeness.

And what do we find in the romance of Tristan and Ysolt? A violent negation of the romance structure. Their sin causes fragmentation—moral, familial, social—and their subsequent adventures, even if entertaining and superficially impressive, end not in reunion, not in a return to harmony and healthy relationships, but to a sterile death marred by painful separation: Tristan dies alone, severed from his fatherland, from Ysolt, and from his own wife. His unconsummated marriage is an allegory for the damage done by unbridled passions and disrespect for familial and feudal bonds—he and his wife are not one flesh, as all married couples should be, but instead represent a perpetual deferral, a unification that is demanded and expected but never attained. In a society where happiness was linked more to a sense of social and spiritual wholeness than to material prosperity or radical autonomy or audiovisual stimulation, the “moral” of the story of Tristan and Ysolt was clear enough: though their physical pleasure was real, though their feelings for each other were real, though their mutual attraction was not devoid of sincere affection, true fulfillment was simply impossible, because their “love” led not to restoration, as does the true Love of the Cross and the empty Tomb, but to rupture.

Longtime readers of Via Mediaevalis know that medieval life was a profoundly symbolic life. In Marie de France’s version of Tristan and Ysolt, the poetry surrounds a central symbol, from which the poem takes its name: Chievrefoil, meaning “honeysuckle.” Marie tells us, in a fine translation by Dorothy Gilbert, that Tristan and Ysolt were like

honeysuckle, which must find

a hazel, and around it bind;

when it enlaces it all round,

both in each other are all wound.

Together they will surely thrive,

but split asunder, they’ll not live.

Quick is the hazel tree’s demise;

quickly the honeysuckle dies.

“So with us never, belle amie,

me without you, you without me.”

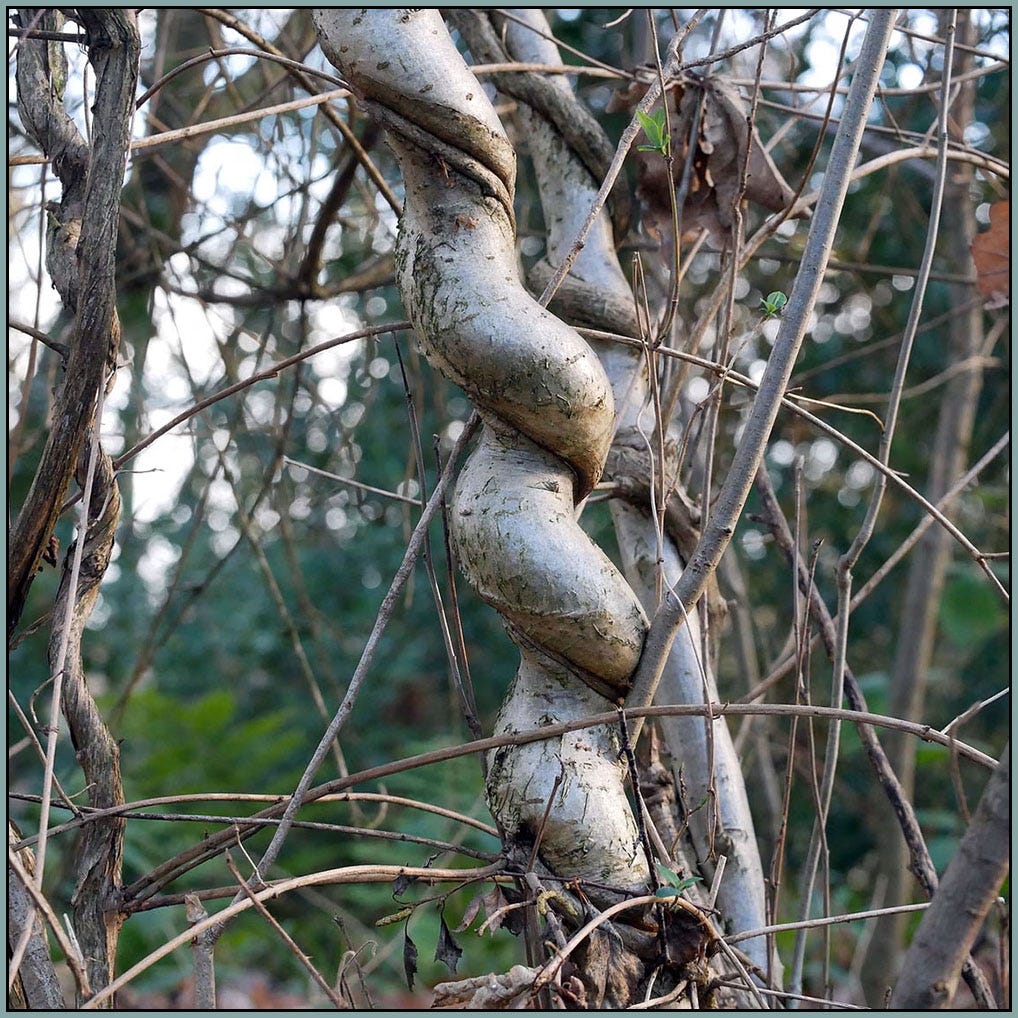

We might be inclined to read this as a nice bit of sentimental “romance” (in the modern sense)—I can’t live without you, we’ll be together forever, and so forth. But for medieval readers and listeners, who probably had far more opportunities to actually see honeysuckle in the wild, the imagery may have been less cheerful. The photo below gives you an idea of what honeysuckle might do to its “companion”—the “embrace” of the honeysuckle is more like strangulation, and the tree, permanently scarred and deformed, is not a pretty sight.

I honestly have never been much more privy about the story than the synopsis you gave, but it has come up from time to time, and this article left me thinking for most of yetersterday about it. This could very well be a stretch from the details of the actual story, but it struck me that maybe the real, enduring significance of it is in what John Senior would refer to as the "unsentimental sentiment" of our primordial nature, and what are now much more developed teachings in the Church on account (at least in part) of the enduring popularity of stories like Tristan and Ysolt. To the best of my knowledge as someone who studied moral theology in college, neither Tristan nor Ysolt had valid marriages to their "actual spouses" since Tristan's was never consumated (an extremely strange detail for those accusing him of the vice of lust!), and hers was by coercive arrangment. Furthermore, their effectively monogamous fidelity to each other even unto death (can anyone actually dare call that lust?) spoke of a far deeper and more intentional bond between them, which was certainly more akin to marriage as God created it to be than in what they had in what were their legal marriages. It is this cataclysmic clash between the dead letter and the living spirit of the law concerning marriage that gives the story its moral ambiguity and the enduring retelling it gets.

Perhaps the real power and meaning of the story is in what could actually be considered Tristan and Ysolt's actual triumph even to today, that (1) marriages are no longer considered valid when coerced, (2) nor are they considered valid when unconsummated, and (3) that sexual passion can - and indeed is meant to be! - a real expression of the benevolent and eternal love between the man and woman as God created them to be. The world in which Tristan and Ysolt lived did not recognize these truths, and so, in a way, they were actually far ahead of their time in terms of what the Church now teaches on marriage.

I would tend to believe that while Tristan and Ysolt would be damned within the standards of that time, they would yet have found mercy before God in having striven for what are now known to be the actual truths about marriage. The truths they pursued and strove to live in their actual fidelity to each other before, during, and after their legal "marriages" to others, are actually far closer to the primordial perfection God created for marriage than the same legal "marriages" they had with their "spouses". That we have come to see and acknolwdge those truths so much more clearly today is precisely because of the romantic tragedies of men and women like Tristan and Ysolt... which is why, in a way, they could be regarded as the true heroes of the story today.

...And that is a legacy which could very well be to their eternal credit in heaven according to God's mercy.

Good article. Nice antidote to 99% of Marie de France scholarship which almost all comes from feminist studies trying to reveal how Marie de France was secretly a 2nd or 3rd wave feminist in the 12th century.