A Dim and Lenten Light to Guide Us

Aristotle, Robert Frost, and the narrow way that leads to life

He who is unable to live in society, or who has no need because he is sufficient for himself, must be either a beast or a god.

—Aristotle

Like the pastel tones of a sun well set, the Christmas season fades. The horizon is Lent, and it darkens.

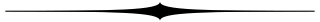

Ash Wednesday, the beginning of the Lenten fast, falls on March 5th this year. It may seem a bit dramatic to suggest that the dusky days of Lent follow so closely upon the radiance of Christmas, but that’s just a sign that we’re not thinking medievally enough. First of all, the Church’s great season of penance and conversion was taken very seriously in the Middle Ages, such that Lent loomed a bit larger in the Christian mind, and cast a longer shadow on the Christian calendar. But more importantly, Ash Wednesday wasn’t only a beginning in medieval culture; it was also the end, or rather the culmination, of the pre-Lenten season known as Septuagesima, which begins two and a half weeks before Ash Wednesday.

Thus, even in years with a late Easter, those ominous recollections—twinges of the hollow stomach—were creeping in not too long after the feasting and festive spirit of the Nativity and the Epiphany had dissipated. When the astronomical-liturgical cycle was in its less gentle phases, Septuagesima arrived in January, thus mingling its gall with the wine of Christmastide, and adding a purplish, penitential hue to the mirthful little lights of Candlemas.

Year after year, generation after generation, beginning in the Early Middle Ages and not entirely lost even today—Septuagesimal emotion has been filtering into the Christmas season for many centuries, and we might expect to find a deep imprint somewhere in the collective consciousness of the West. Perhaps this has something to do with the strangely bittersweet character of the month of January, or even of the Christmas holidays themselves. Alfred Lord Tennyson said it well:

But they my troubled spirit rule,

For they controlled me when a boy;

They bring me sorrow touched with joy,

The merry merry bells of Yule.

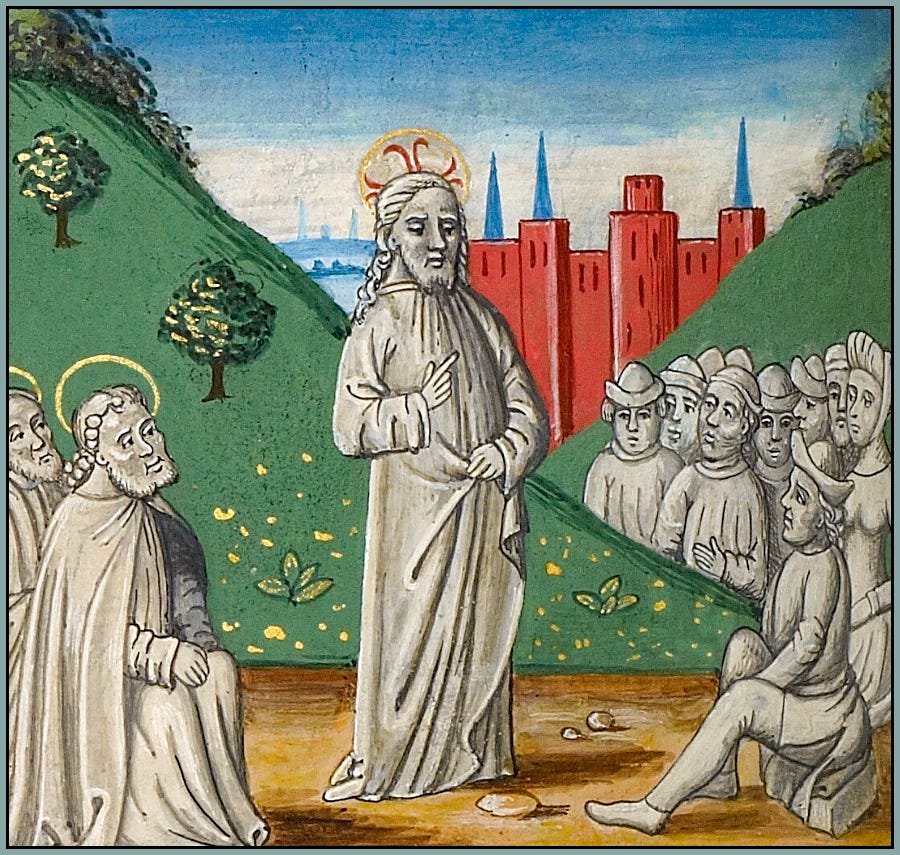

Such thoughts as these lead my mind away from the mirthful celebrations that arrive in December, and away even from the romantic joys that accompany marriage, the mysterious sacrament of which we have spoken so much lately. I am looking instead down another path, one which modernity in general does not take, but of course there are exceptions, heaven be praised, who “prove” the rule. It was, sometimes still is, the path of silence, chastity, severity, solitude, fasting—and not just during Lent. The path also of poetry, much of it co-authored by Almighty God, then translated into a language not so much dead as immortal. And of song, a singular form of spiritual song, sung to the divine Spouse in the sacred half-light of a candlelit church. Even in medieval civilization, the Mediterranean world’s high tide of faith and fervor, it was the path less traveled by.

I wonder how many of you can read that last sentence without remembering, or at least somehow feeling, the famous poem by Robert Frost. “The Road Not Taken” has become a canonical expression of choice and its mysterious power to transform a human life; perhaps it has even reached the status of cliché, though I hope not, because it’s a fine poem.

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, And sorry I could not travel both And be one traveler, long I stood And looked down one as far as I could To where it bent in the undergrowth.

When you read poetry, do you ever sense that the flow of time, otherwise so inexorable, is somehow altered? That something resembling the everlasting Now of the Empyrean, or the mystical timelessness of a medieval monastery, is brought the slightest bit closer to your soul? Poetry can do this; rhyming, in particular—when it is skillful, and doesn’t draw too much attention to itself—can do this, because its effect is felt before its moment has arrived. The first time you encounter this poem, the word “both” is mostly a sound unto itself. But great poems are not written to be read only once; if you’ve read it before, or heard it before, if there is some trace of it in your memory, “both” echoes with a word as yet unspoken: “growth.”

In poetry, as in song, there is this vaguely prophetic quality, where the meaning of a word is enriched by another that has not yet entered the conscious mind. Orpheus, the archetypal poet and musician of ancient Greece, was also a prophet. Poetry, the archetypal literature of the human race, and the first language of the soul, can be a place where thought and time are united and then refashioned—into something less linear, more cyclical; less mechanical, more cosmic; less logical, more paradoxical. Something more monastic, we might say.

“Two roads diverged in a yellow wood…” The poem—extremely well known, widely admired—is a commonplace in modern culture’s metaphorical understanding of a theme that one and all must someday face: the choices of which a life is made. Do we find it strange, disconcerting even, that Frost wrote the poem not in seriousness but in jest? That he wrote it not as a gift of profundity to the world but as lighthearted humor for an indecisive friend? Not very strange, I would say. Poets don’t always know the full import of their own poems, much as prophets don’t always know the full import of their own prophecies. Poems, furthermore, are composed of language, and language comes from God. Its powers surpass the minds of those who shape it, much as the gold shines ever new when the goldsmith’s body has turned to dust.

“And sorry I could not travel both / And be one traveler.” The choice must be made. We have but one life, and it must go either this way or that; we have but one body, and it must dwell either here or there. “In my monastic hermitage,” St. Peter Damian tells Dante in canto 21 of Paradiso,

I was made so strong in the service of God that, eating no more than the juice of olives, I easily endured both heats and frosts, content in my contemplative thoughts.

Occasionally it is possible to go back, to choose again. Very often it is not.

Then took the other, as just as fair, And having perhaps the better claim, Because it was grassy and wanted wear; Though as for that the passing there Had worn them really about the same.

Are the two paths different, or not? Frost isn’t clear on that point; or rather, he is clearly unclear. One has perhaps the better claim, but then they’re really about the same—or is this actually just a game, the type we play when afraid to choose?

By the end of the poem, we’re still unsure if the paths look very different. But the heart sometimes knows what the eye cannot see—something does set them apart, and it’s more than just the direction they take through the thick undergrowth of life:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I— I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference.

“Either a beast or a god,” says Aristotle. That’s how extraordinary it is to leave the world behind—to choose the less-traveled path, leaving home and possessions, money and lands, family and friends behind. Aristotle, however, had not the good fortune of knowing Benedict of Nursia, who was neither a beast nor a god. Rather, he was a saint, and we’ll talk more about him on Tuesday.

Thank you for this reflection and for the Frost poem within it.

As it happens, I spent this afternoon transcribing my favourite poems into the blank pages of a book I was sent recently: By Heart: 101 poems to commit to memory, selected by Ted Hughes.

I have decided to learn the ones I love in this selection 'by heart', both in order to exercise my memory muscle and to ponder the words of these poems when I recite them to myself.

Robert Frost's Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening wAs the first I learnt. I have now memorised 10 poems - and was planning to look up The Road Less Traveled when I happened to read your essay. Now I have transcribed it!

And I also wrote an article about poetry recently for an online magazine, in which I defined poetry as 'the language of the soul' - which of course it is.

And I meant to add, as you say, that great poems always say much more that their author is aware of. When I think of The Road not Taken I think of the beginning of St John's Gospel in which he says 'God who enlightens every man born into this world...'

I take this to mean that at some time in our lives God offers us the choice of the narrow road leading to Him - or the broad road that doesn't.

We all come to the place of the two roads...