Today we will conclude—or maybe just pause, because there is so much more to say!—the Via Mediaevalis series on angels in the culture and theology of the Middle Ages. The previous articles are listed below.

We cannot end this journey through medieval angelology without addressing a topic that is, alas, not nearly as uplifting as the others in this series. It is, in fact, quite the opposite of up-lifting. It’s positively down-dragging, both spatially and emotionally, but it must nonetheless be faced: First, because we’re in Advent, and the newborn Light will be all the brighter if our eyes have adapted to darkness. And second, because not all the angels, as we discussed on Sunday, enjoy mankind’s poems and paintings—or rather, some angels “enjoy” only those poems and paintings which are as depraved and grotesque as they are.

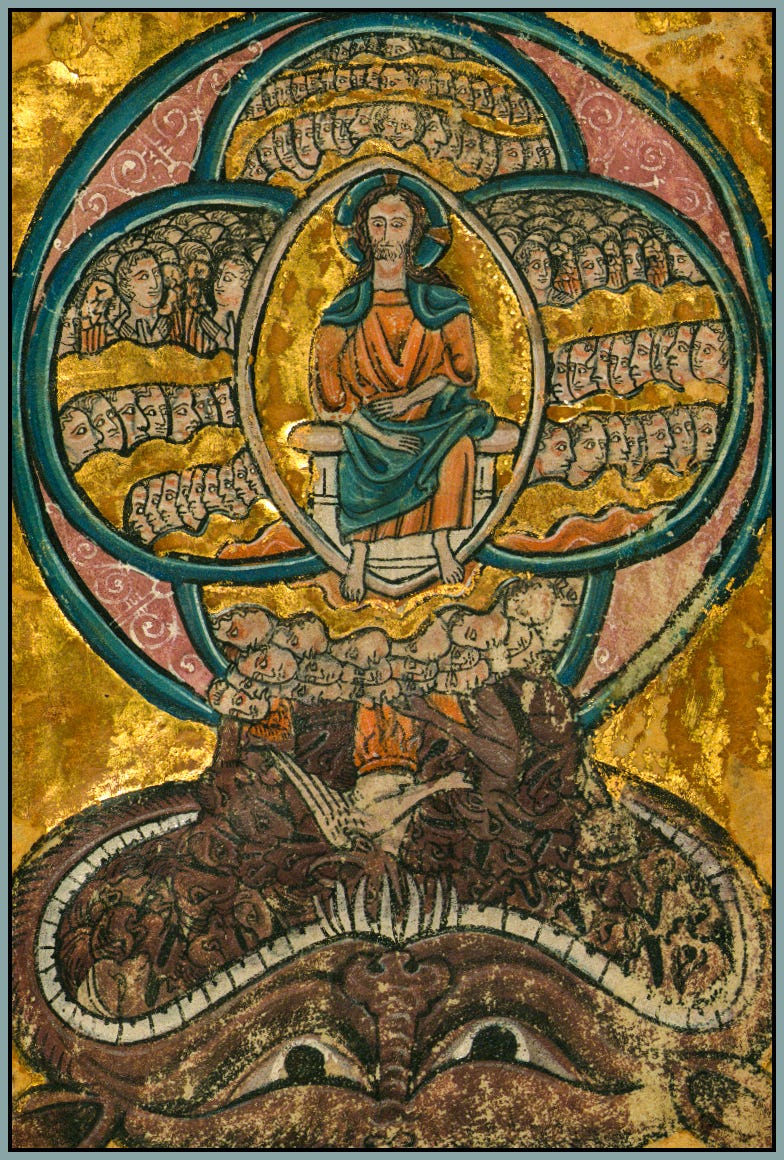

I speak of the angels who, in the medieval imagination, remade themselves into beasts and fell into the flaming jaws of the underworld. We call them demons, but they are demons by virtue of their state, not their nature. From an ontological perspective, they are simply angels; we do well to remember this from time to time, because the angels, as the last two articles emphasized, are like us. The difference between angel and demon—between beauty and degradation, joy and misery, glory and ruin—begins in that same dread faculty which leads the great drama of human life to either commedia or tragedia: the freedom, and the ability, to choose.

Many there be that complain of divine Providence for suffering Adam to transgress; foolish tongues! When God gave him reason, he gave him freedom to choose, for reason is but choosing; he had been else a mere artificial Adam.

—John Milton, “Areopagitica”

The fall of the angels is not clearly explained in Sacred Scripture; it is not easily investigated through theological methods; it is not even fully comprehensible to the human mind. And yet it is, without doubt, one of the most significant events in human history.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Via Mediaevalis to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.