Now cracks a noble heart. Good night, sweet prince,

And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest!

The lines above are not as idyllic as they may seem. Out of context, they sound like something Juliet might have said when bidding farewell to Romeo. But it’s actually Horatio who speaks them, and they are addressed to the corpse that a few moments earlier was his friend, Prince Hamlet.

Hamlet begins his final speech with a deceptively simple statement: “O, I die, Horatio!” This is his answer to the question he pondered back in Act III, and which many others after him have pondered, and which is also the most famous question in Western literature: To be, or not to be?

Notice that he says “I die,” not “I am dying.” The latter expression sounds more normal to us, and yet it is, strictly speaking, impossible. Not as spectacularly impossible as what Ernest Valdemar says in Poe’s macabre short story: a mesmerist manages to hypnotize Valdemar at the moment of death, and in this hypnotic state the man declares, “Now—I am dead.” In the words of the French literary theorist Roland Barthes, this is human language descending to “le point vide” and reaching that which is “radicalement impossible”:

The conjoining of the first person (“I”) and the attribute “dead” is precisely that which is radically impossible: it is the empty point, the blind spot of language…. The sentence “I am dead” asserts at the same time two contraries (Life, Death).

To say “I am dying” is similarly contradictory: speech is possible only when one is alive, and the states of life and death—of biological life and death—are, as Epicurus pointed out, mutually exclusive: “when we are, death is not come; when death is come, we are not.” The phrase “I am dying” does not perplex us, though, because we interpret it as something that is, however disquieting or tragic, a perfectly natural stage in the earthly journey of mortal man: “I am approaching death.”

But Hamlet’s declaration—“I die, Horatio!”—is different. It does not report a specific bodily state, and it need not refer to an ongoing process. It is, rather, a statement of general truth: “I, Hamlet, am a man who will die. I, Hamlet, am a being whose life is defined by death.” The beasts—which, as the Psalmist observes, “have not understanding,” and which, as the Psalmist again observes of the heathen idols, “have mouths and speak not”—the beasts die only once, and their death is the work of one swift moment. But human beings die many times, insofar as our life is punctuated and permeated by expectations of its end, and our death is made long—very long—by minds that so often brood upon it, and hearts that so often fear it, and poets who so often sing of it. “In the midst of life,” says the Book of Common Prayer, “we are in death.”

When Hamlet reached le point vide, the empty point where death is an immediate reality instead of a philosophic exercise, he realized that “to be or not to be” is not the question. “I die!”—this, in two words, is his peroration, his resounding conclusion to the grand and searching and anguished speech that was his life. This, in two words, is the glory of a redeemed humanity whose life is ever overshadowed by death, but whose death is eternally illumined by life. This, in two words, is the magnificent paradox of our earthly pilgrimage through the dark night of Lent toward the bright light of Easter. Haec nox est, reads the Paschal Exsultet, de qua scriptum est:

This is the night of which it is written:

The night shall be as bright as the day,

The night is glory to me and delight.

Nox ista vigiliarum Domino, reads the Book of Exodus, quando eduxit eos de terra Aegypti:

That was a night of vigil unto the Lord, when he brought them out of the land of Egypt. That very night is of the Lord, and is to be a vigil for all the children of Israel, from generation to generation.

“I am the resurrection and the life,” saith the Lord, “he that believeth in me, though he die, yet shall he live.” Hamlet was a scholar at Wittenberg, like Martin Luther, yet in his dying words he joins the company of poets, proclaiming that the ultimate mystery of human existence is to be and not to be.

And “the rest,” as the poor Prince of Denmark declares with his final breath, “is silence.”

It’s mid-Lent in a medieval town. The celebrations and excesses of Carnival have faded from memory, and even the more moderate and legitimate pleasures of life carry this strange sense of ambivalence, vexation, vanity. Those who can read might hear replaying in their minds, almost as in a dream, a collage of verses from Ecclesiastes:

I said in my heart, Come, I will prove thee with joy: therefore take thou pleasure in pleasant things: and behold, this also is vanity…

I said of laughter, Thou art mad: and of joy, What is this that thou dost?…

I have made my great works … gardens and orchards … cisterns of water … herds and flocks … silver and gold … treasures of kings…

… and behold, all is vanity and vexation of spirit: and there is no profit under the sun.

For weeks now—no weddings, no banquets, no dances. Faces look a bit hollower, and midsections a bit narrower. Some appetites are raging, while others, thanks to the strange phsyiological effects of a long fast, are languishing. Smiles and jokes and hearty embraces don’t come quite as readily as they did in January. Laborers are forgetting what it feels like to be satiated and buoyant while walking out to the fields each morning, mothers are a little less tolerant of the children’s mischief, fathers reflect gravely on the follies of their youth, and folks of an especially penitential disposition might be feeling drained and half-dead.

And then—laetare. They’re all in church for the Fourth Sunday of Lent, and this is the first word of the opening prayer: rejoice. Though laetare might look like an infinitive form, laetor is a deponent verb, which means that laetare is actually a command: rejoice! That’s what the medieval Church tells them to do on this dark, heavy day in the middle of Lent:

Rejoice, O Jerusalem, all you who love her,

gather as one and rejoice with joy,

you who have been in sorrow.

In the midst of life, we are in death, but if that’s true, then in the midst of death, we are in life. How well the Church knew it then: the enchanting dance of joy and sorrow that are the days of man upon the earth. Even poor Claudius—Hamlet’s nemesis, and a base sinner, “that incestuous, that adulterate beast”—had some idea of it, had some idea of living the mid-Lenten spirit and walking through the world “with a defeated joy, / With an auspicious, and a dropping eye, / With mirth in funeral, and with dirge in marriage, / In equal scale weighing delight and dole.”

To be and not to be, that is the question of Christianity, a religion so tremendously and sublimely paradoxical that not even the poets dared to imagine it. This is the religion of a Virgin who is also a Mother, of a God who is also a Man, of a Lord who kneels as a servant, of Life that is sentenced to death, of death that renews all life, of a Church that is also a Body, of a Body that is also our Bread, of a world that is also a story, of a heaven that is also within.

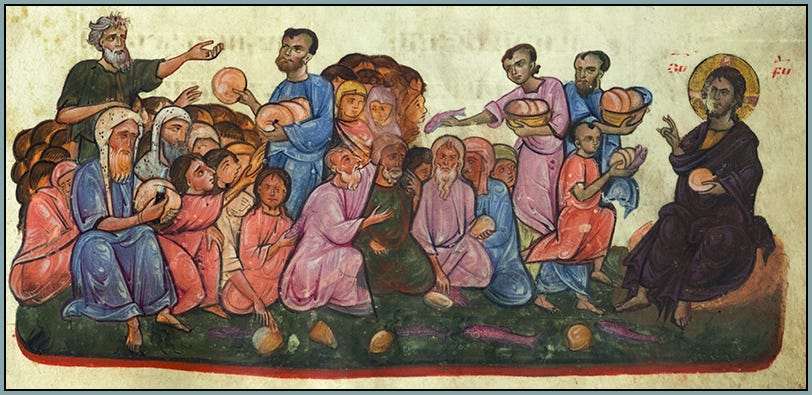

You see it in the illuminated missal above, which has the first few words of today’s opening prayer. Laetare is misspelled, relative to classical standards, as letare; three of the words are abbreviated; and diligitis is broken off right in the middle of the word, to be completed on the next page without so much as a hyphen by way of apology. Medieval folks, though supremely religious, didn’t stress over details, and they didn’t fret about restoring the “high culture” of pagan Antiquity; one is tempted to say that they were just too busy having fun with fantastical creatures painted around sacred texts and bagpipe-playing swine carved into monastic choir stalls. “Except ye be converted, and become as little children…”

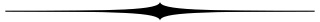

The painting that precedes the text represents the Gospel passage for the day, which recounts the miraculous feeding of the five thousand: “There is a lad here, which hath five barley loaves, and two fishes: but what are these among so many?” Medieval mothers and fathers must have heard this question echoing in their minds the next day as they looked at the dinner table—not only was fasting imposed on all who were old enough, but this was early spring, when the soil was still cold, the cellar was almost empty, and the cows weren’t making much, if any, milk. What is this, Lord, among so many? The story, however, was perfectly chosen for mid-Lent, and those mothers and fathers remembered how it ends: a little goes a long way, if you place it in the gracious and all-powerful hands of the good God.

Still, though, miracles are few, and a meager meal that is blessed and offered to the Almighty will probably continue to look and taste very much like a meager meal. Fortunately, their minds were well attuned to paradoxical realities, and they knew that scarcity was somehow abundance, and that abundance was somehow scarcity—for the God to whom they offered their bread was also the God who said “Blessed are ye that hunger now, for ye shall be filled…. Woe unto you that now are full, for ye shall hunger.”

HAMLET: A man may fish with the worm that hath eat of a king, and eat of the fish that hath fed of that worm.

CLAUDIUS: What dost thou mean by this?

HAMLET: Nothing but to show you how a king may go a progress through the guts of a beggar.

This entire essay, if you can believe it, is an introduction to other topics that I want to explore in the next two or three posts. Immediately after Hamlet—famously troubled by mortality, and as the excerpt above suggests, not averse to meditating on bodily decay—has shuffled off this mortal coil, Horatio entrusts him to those mysterious beings that are never subject to mortality, and will never experience bodily decay: “Good night, sweet prince, and flights of angels sing thee to thy rest!”

I have already written a great deal about angels here at Via Mediaevalis. However, I would like to return to them in this sacred season of Lent, when Christians are especially mindful of the appetites and sufferings and frailties of the flesh, and perhaps especially sensitive to the paradoxical destiny that is bodily death, by which we pay the wages of sin. By discussing the development of angelic theology in the early and medieval Church, we’ll see how angels ease the psychological burden of our mortality and serve as an inspiring, glorified reflection of the human race.

My previous essays on medieval angelology are listed below. For those who subscribed after mid-December, I hope that you can find time to read some of them, because I really do think that you will enjoy them.

This sentence is a delightful recitation of the paradoxes that show a glimpse into the mind of God:

“This is the religion of a Virgin who is also a Mother, of a God who is also a Man, of a Lord who kneels as a servant, of Life that is sentenced to death, of death that renews all life, of a Church that is also a Body, of a Body that is also our Bread, of a world that is also a story, of a heaven that is also within.”

“O the depth of the riches of the wisdom and of the knowledge of God! How incomprehensible are his judgments, and how unsearchable his ways!” Romans 11:33.

I enjoyed this so much. It was delightful to me. Thank you!